(It’s more about the train than the bike)

OS Landranger – 179

34 miles

There’s about 15 minutes before the train leaves St Pancras International station. The night before I had purchased a dirt cheap, on-line ticket, that would take me one way to Herne Bay. When I logged on and started searching for journey options, the last thing I expected was to be repeatedly bumped by some of the stations I’d assumed would come up with the goods, like London Bridge and Victoria. Instead, and by dint of persistence, I was directed to St Pancras as the main option. Surprised to say the least, but nevertheless quite pleased because St Pancras is the nearest London mainline terminal to my home, I secured the purchase but remained sceptical that there would be a train to convey me in the morning.

And so there I was, with plenty of time, at a very familiar location, but without a clue which platform I was supposed to be at. My first mistake was to go to the Thames Link platform gates. Scanning the screen there was no indication that any of the trains over the coming half hour were going to be going anywhere remotely close to the north Kent coast. Under any other circumstances I wouldn’t have been that bothered and would have adapted to the situation by giving up the ghost and going home. Today however, was different. At around 2pm I was due to meet with two old friends at Margate. They were going to join me to complete the ride ending at Deal, and where they lived. And of course, just because I always seem to want to over complicate things, I’d calculated that I could start the day at Herne Bay and pootle along the north Kent coast as an added extra to what could be considered my ill-judged coastal mission. To be confronted by the absence of any means of conveyance to Herne Bay, or indeed Margate, was now cause for panic and irritation. I double checked the ticket which I’d liberated from the machine in the concourse and even without my essential glasses I could see that St Pancras was indeed the departure terminal. Five minutes later and after extensive roaming of the concourse and another digital board showed that a train did indeed exist but on the high-level platform.

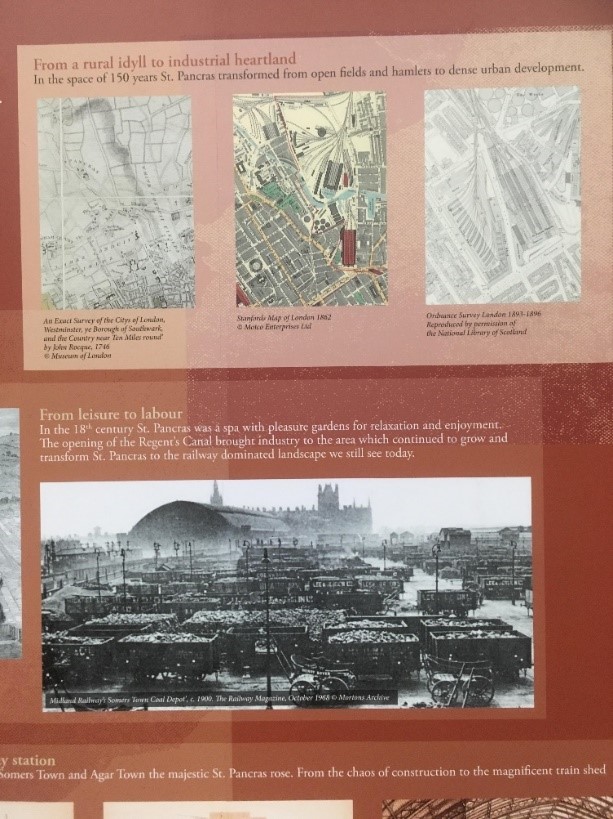

If you haven’t been to St Pancras station since the 1970’s or 1980’s it’s undergone something of an image change. Back in the late 70’s I lived in Leicester, and arguably studied at the University. A few times each year I’d take the train from London to Leicester, either on my own, or with other comrades in learning from London and the South. Even through rose tinted glasses it’s hard to comprehend how, in the years when the old world was rapidly slipping away for ever, what a complete dump St Pancras was.

When I eventually managed to get the lift to the new upper level, and still with some time to spare, I came across a small pictorial exhibition installed to celebrate the stations 150-year history. Although by the 1970’s the old and extensive coal yards which collected, and then fed the homes and industry of the city, were gone, and the remaining land lay dormant for decades until the erection of the new British Library, the hulk of the old station, threatened with extinction, still echoed to the sound of clapped out diesels and stank of discharged fuel, piss and the smoke from a hundred cigarettes. Millions of red bricks were hidden behind layers of black soot and the only colour on display was the rust that clung to the massive iron structure, and the statutory yellow warning markings on the front of the handful of engines that serviced the half empty platforms where grey and mystified “customers” moved like zombies through the smog. And they say nostalgia is dead?

“…the majestic St Pancras rose..”

“…the majestic St Pancras rose..”

At the end of each academic term (you’ll need to use your imagination here), everyone would head off north, south, east and west to home towns where infrastructures were rapidly crumbling and the established consensuses were breaking down. For the London crew, and unless a precious lift in an unsafe mini Cooper or banged out old Hillman Imp was on offer, invariably involved a long and featureless train journey through the midlands rain to St Pancras. If the buffet was open you were duty bound to drink a couple of tins of antiseptic lager or bitter to steal yourself against the reality of a few challenging weeks back home. Arriving at St Pancras, if you were with someone and still putting off the moment when the underground would suck you further to your temporary doom, a last Grotney’s beer and a damp pork pie in the station bar was mandatory.

What can I say about the old bar at St Pancras station? It existed, if that’s an adequate description, at the front of the station and between the platforms and the busy Euston Road that lay beyond. If you have in your head an image of what a “bar” looks like now, can I just say that at every level it is not anything like the reality of the old St Pancras bar. Not a single redeeming feature. In a station that was built to a grand, almost imperial design, every possible effort had been put into the bar to minimalise detail, impose conformity and Formica, and beat the living daylights out of the travellers will to live. To accurately date the last time the floors would have been cleaned would have required the skills of a forensic scientist.

If, after the beer, fags and crisps, you still had some unaccountable desire to continue on your mission, stepping out onto the Euston Road to get to the Underground was like an assault on your very being.

Some years ago I stood on the pavement at the junction of Euston Road and Pancras Road, that runs up between St Pancras International and Kings Cross station. It was sometime during a school holiday and crowds of people were pouring out of the stations and underground. A family emerged from the bowels of St Pancras. A little boy, maybe 6 or 7 years old, looked up and across the Euston Road towards the artistically painted bulk of a Victorian bank building on the south side and as his jaw dropped shouted “Wowwwwwwww!” His slightly older sister, who was holding his hand to prevent him being swept away, looked down, and in an almost faultless Jenny Agutter voice simply says “Yes. It’s London!” She too was in awe. The innocence and genuine disbelief of the moment made me chuckle but my own memory of the same experience back in the 1970’s held no sense of innocence. A few months away in the provinces was always enough to soften the edges, and weaken the spine enough to receive what felt like a metaphorical kick in the groin when stepping out of the station into the thronging mass of “old” London.

“The first train to Herne Bay? Let’s see. Ah yes……it leaves in 32 years sir! The bar’s by the main entrance if you’re thinking of waiting.”

As I stood looking at a grainy black and white picture of the old shell, with a Peak class locomotive in the foreground, and one of the “Age of the Train” 125’s beyond, and with the memories of the petrol stained platforms pouring back, I tried to equate what the station (International of course) had metamorphosed into now. In truth there was nothing much to ruminate on other than to bless and thank the planners, designers and visionaries who somehow saw beyond the stagnation, and over several decades (visible to me most days at the time), pulled out all the stops and created this new masterpiece.

1st August 2018, and a couple of generations on from the gloom, and I am through the automatic barriers and heading for the carriage where they allow you to place the bike outside the toilet. It happens to be the first carriage on the Javelin, which is advertised as the fasted train in the UK. I don’t know how many of these there are in service but in that fine railway tradition, each has its own identity, and the theme chosen to name them are contemporary top UK athletes. On this occasion it’s Mo Farah who’s going to whisk me to Herne Bay. Note to self – when back email the operator and see if they’ll agree to paint the faces of the athletes on the front of the engines.

Though I’d arrived with plenty of time and, I thought, in advance of the usual scrum, I had badly misjudged the position. Not unlike the start of a sprint race, hoards of people, many pushing lightweight prams, were dashing from the barriers and heading for any empty seating still available.

Reader: can’t you just get onto the bloody bike trip?

Errrrr…hold your horses. These are important details. I managed to get the bike on the carriage before being overwhelmed by humanity and duly strapped in the bike. One of the features of the WC, come bike carriage, is that it also trebles up as the carriage for wheelchairs and people with prams. Small children were shepherded on, and at least two made an immediate wild-eyed dash to the toilet, curious to find out how the door opened and closed and in the process releasing noxious fumes every couple of minutes until the point where the custodian had managed to insert the pram with the younger child/ren between the other prams cramming the isles and reasserted some control. Under less stressed conditions this carriage arrangement is entirely practical, given the close location to the WC but, as the train eventually started to pull out of the station, the reality of the situation was beginning to hit home. A squeeze was already underway by the time the fasted train in the UK headed north and then snaked to the east and onto Stratford International (which of course was anything other than international until a handful of years ago). Although I had a drop-down seat, the fresh wave of humanity clambering on at Stratford, and including a middle-aged woman with her bike, more pushchairs and more kids than in an average school playground, it was coming under intense pressure to be surrendered. I gave it up. A conversation started up with the biker woman during which we concluded that it was indeed the school holidays, that it was a lovely day, and that we were on the first train after the rush hour with the super knocked down family fares. Concluding also that a serious misjudgement by ourselves must have occurred.

At Ebbsfleet (International of course), with the train now across the river and in Kent, the doors opened. No-one got out. Many more got in, including heroically a group of women with their children, buckets and spades and one pushing a double buggy with two very young children who instantly started screaming. As the bodies piled on in, and complex internal manoeuvres of other buggies, wheelchairs and bikes took place, the realisation of how hideous the next hour on what was obviously the slowest Javelin in Kent, sank in. The biker woman was now squeezed towards the end of the toilet zone and she’d given up on the idea of making it to her meeting in Margate on time. I had now been edged round to the door, the bike no longer attainable even if I had felt the need to rummage in the pannier for nothing in particular. What was blindingly obvious to all was that the previous night we had all been on-line and found the bargain bucket, first after the rush hour, only two remaining, tickets to paradise. For most, paradise would be Margate but at this moment it seemed to be a long way off. No doubt thoughts of the return journey, when the kids would be stuffed with toffee apples, exhausted after endless running, splashing and falling over, still high on throwing coins into flashing machines and then screaming for their beds, would be nudging into the worried heads of the mothers (just saying – there were no dad’s) and older children who knew the score from previous indulgence.

After Ebbsfleet any sense that this was the fastest train in the UK quickly fell away as it stopped at nearly all the stations lining up along the route. Each time more humans bundled on and more internal reorganisations took place. Access to the toilet was now almost impossible. At one point a young teenager, with a walking disability, did make a successful attempt, but not after having to squeeze, climb and push through the sea of people, wheels (of all sorts) and dirty looks that had become the on-board assault course. Almost certainly nothing like this was happening in first class, wherever that was, but strikingly two men, with clip boards and an obvious association with the train operator, stood with the crowd and observed all of the carnage unfolding as we crawled on through Kent, and then over the Medway and further east. Perhaps there was nothing they could practically do, or it wasn’t in their JD, but it felt deeply uncomfortable that they made no attempt throughout to intervene, even if it had only been to help the people most in need to get to and from the toilet by the use of some helpful or calming words. They never came, and to my shame I later regretted not saying anything to them.

With a few stations to go before Herne Bay (and if at any point you see the words “Herne Hill” instead, excuse me for the error but I’m south London at heart and can sometimes get me words muddled like), I get a text about nothing in particular from a good friend who was also on a train but going from Ashford to Hastings. I reply:

“Currently on train to Herne Bay sitting outside toilet. Very unsettling.”

Shortly after a reply comes through to explain that the Ashford to Hastings train is entirely civilised and they are enjoying the fine views of Romney Marsh and hoped I would survive. I replied:

“This one is hell on earth and no space to swing a bike chain though am now quite tempted.”

There’s a reply with a smiley emoji which I interpret in a number of ways – all probably incorrectly. I send one last text a bit later.

“I won’t text again but actually this is awful and probably breaching all health and safety.”

And that last point is important. Trains in the UK are of course inherently safe but accidents do happen. The number of people on this train, with a very high number of children, including toddlers, was excessive. Add in the mobility paraphernalia (which of course included my bike with all it’s pointy metal bits) and then a crash or derailment, at any speed, and the consequences would be obvious. If I thought that this particular train was bad, others have told me about their own hideous experiences on other lines and on much longer journeys this summer. You then have to wonder at what point the train operator and the companies that sell the tickets, whether they are slashed down affairs or not, look at the on-line traffic and say, enough! Full. No more space. It may end up being a disappointment to some, but at least it would be clear and understood. Why should trains be any different from buses and planes? Presumably you’re not allowed to cram standing passengers on the top deck of a bus for a reason, and the same for planes (not the standing on the upper desk of course). It is actually possible to run more trains. It’s not easy, and how it’s coordinated is an art form, but it can be done. Although you can, of course it may not be as profitable. But if there’s demand, and without any doubt on this hot and sunny first day in August, with the school holidays still fresh, there clearly was, maybe some advanced planning and a bit of imagination could have eased the chaos. Just some random thoughts – probably impossible.

At Herne Bay, and with the improbable task of getting both me and the bike off “Mo Farah,” (who, let’s face it had just had a dismal run) achieved, I silently thanked no god in particular that I would not be joining the herd back to London later in the day. Inhaling deeply and checking all was okay with the bike, I left the station and headed off, skirting a park to the left and then down to the seafront.

Herne Bay station and escape from the network

Herne Bay station and escape from the network

Now late morning, I had nearly three hours to complete the route from the truncated pier at Herne Bay to Margate Station, where two old south London friends, now living the life in Deal (and with at least one of their off-spring living ironically in Herne Hill), would, if they made it, be waiting for me. The previous day I’d communicated my intentions for the day to another friend. He replied “Herne Bay, Christ you won’t linger there.”

And he was right, I didn’t, but putting those negative vibes aside there was nothing offensive about Herne Bay. Its long promenade held some appeal and heading east there were some good quality Georgian and Victorian buildings which culminated in a pleasant looking white panelled pub called the Ship Inn, which seemed to mark the end of the sea front. A wide concrete road continued along the beach for about a mile. The beach, a mixture of shingle, sand and numerous groynes. A perfect day and an almost motionless sea (I think it’s safe to say that by Herne Bay you are beyond the Thames estuary and into North Sea waters). Every so often a commotion on the surface some yards out would indicate marine activity. On the road and on the beach, there was much less activity with only a small number of people straying this far from the chip shops and cafes. Pleasant indeed but no seals!

SPQR and all that

SPQR and all that

Low sandy cliffs ahead ended the prospect of further wheeled progress along the front, and so up a winding road and west through a residential area with bungalows and modest housing. Then east again along Bishopstone Lane and a gentle gradient down through a wide grassed area leading to the edge of the cliffs before the dominant feature of Reculver church towers rose ahead. It had been three hours at least since a warm refreshment so before making further hay I decided to stop and have a coffee and light bite at the modern, wood framed visitor’s centre café. There didn’t appear to be any kind of fixed community living here. A large static caravan site reaching inland suggested a place for weekend breaks and longer stays for retirees but that was about it. I ordered a coffee and a cheese and onion crepe (sausage rolls don’t seem to be on offer which is always a bit of a disappointment on a bike ride at around this time of day). The coffee arrived first and was surprisingly good but annoyingly gone by the time the main event materialised. The immediate concern from my perspective was that for some, perhaps parochial reason, chef had decided to garnish the savoury delight with a chocolate drizzle. I’m confused and put off by this touch, but a tad more disappointed by what a bland affair it is. Bland or not it was instantly attracting the interests of others, because within seconds of the first bite I was busily beating off a constant stream of wasps that honed in from the car-park in an attack formation not unlike Zero’s at Guadalcanal in ’42. With this new threat, and conscious that I had previously been stung by curious wasps that zone under the table and seem to get some kind of kick from seeking a landing site on ones thighs when wearing shorts, I was anxious to get on with the task at hand. Now, forced to eat quickly and in the hurry, I make a rookie error and napalmed the roof of my mouth, which had the knock-on effect of nullifying what little taste the dish already held. The crap crepe is gone in a minute and then so am I. Riding on, and simultaneously caressing the scorched tissue that lines the pallet with my tongue, I’m soon at the ruins of Reculver.

What’s left of the Roman fort, which was built early in the conquest and would have had a commanding position standing on, albeit, relatively low cliffs, is limited. In fact, what is left is probably just the area that is flat and grassed and which is now covered in impressive mole hills. Indeed, about half of the flat area, where legionnaires would once have lingered, has long been washed into the sea. What stands above ground is the remains of a large church constructed in the 12th Century, with two dominant towers. At some point it came with a significant spire too, but like the Roman fort, efforts to sustain a congregation and religious footprint were surrendered a couple of centuries back when the cliffs eventually, and inevitably, crept too close. You could, of course, conclude by this that all good things come to an end eventually. That’s one possible way to look at it, though for the sake of balance there is of course an alternative take on these outcomes. For better or worse, coastal dynamics have shaped human behaviour here, which for both the Romans and the Ecclesiastical has been something of a terminal retreat.

Commanding the heights – Reculver

Commanding the heights – Reculver

Within a short distance I’m back on a coastal walled path with fields and marshes to the right and the sea, beach and it’s associated groynes to the left. It’s more than a path and the concrete makes for easy going. The land to the south is, in historical terms, relatively new. To the east is the Isle of Thanet, and the Roman soldiers at Reculver would have observed a very different landscape to the one now. Thanet then was an island and with a wide channel between it and the mainland. Now there is a board that explains how the present landscape emerged when the channel started to silt up over the centuries that followed the Roman withdrawal, and at its centre is the River Wantsum.

The word “wantsum” for me, and no doubt many of my generation, comes with some historical baggage. As a teenager growing up in south London, at some point around 1970 or 1971, I lost interest in hanging around with the local hooligans, who at the time happened to be skinheads, and started to grow my hair. This was as much a result of a shift in musical taste as it was because the main skinhead thought it was a good laugh to throw lit “bangers” at me and other weaker cult members. An act of undying loyalty to the head “skin” rested in the victim being stupid enough to laugh off the incident and even suggest that it would be funny to have another firework thrown at them. Sadly, I lacked the same gumption and required feelings of loyalty. After one banger was flicked casually over the main skins shoulder and bounced off my head, before igniting a foot or so away, I was prompted to make some sort of pathetic excuse about needing to go home and then spent the next few weeks desperately trying to avoid the marauding band of morons. At that time unfortunately, like ants stretching out their foraging tentacles in all directions, there were skinheads every-bleeding-where, and on the hunt for any stray and elusive Greasers. It was only a matter of time before someone, always backed up by a large group of similar minded, would sniff you out, normally in an alley, or on exposed waste ground, and utter the words of no adequate response. “Oi mush, you want some c…?” It never mattered much whether you did or didn’t “want sum” but somehow I managed to avoid any major thumping’s through my teenage years, although of course many didn’t. There’s no explanation for this, but as I headed towards the Thanet towns, and past the trickle of water that’s now left of the great river, I thanked my luck stars that the merry moon stompers of south-east London seemed to have bigger fish than me to fry in the early 70’s.

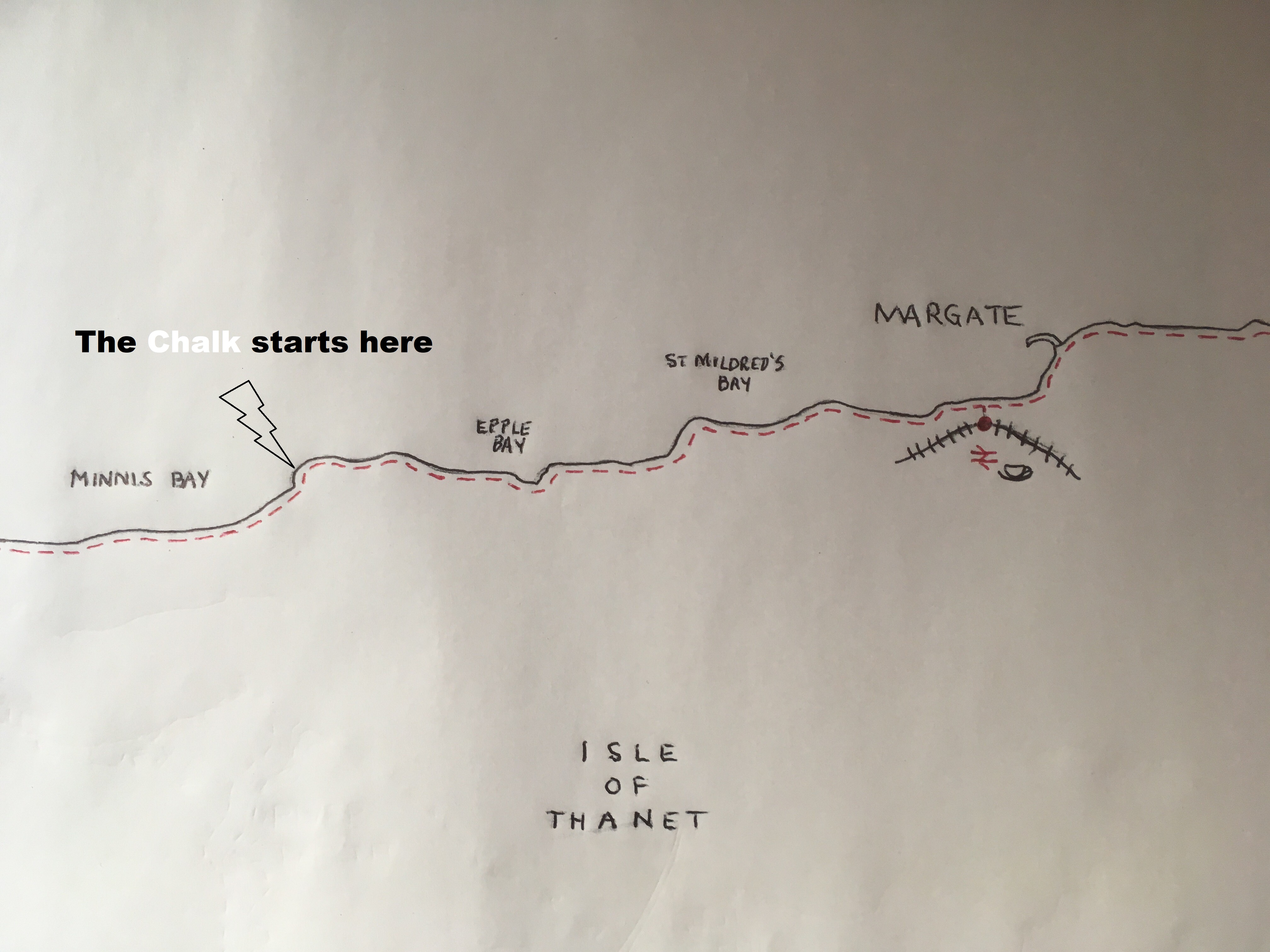

At the end of the alluvial plain, the new underlying structure makes its first appearance above land. The dominant bedrock of much of the southern coast is chalk. At Minnis Bay, the first of a series of broadly similar small resorts that track the north coast, low white cliffs rise past the beach and a large man-made tidal pool, where exuberant children dangle lines with weights on into the water and then squeal with utter delight if they are lucky enough to pluck a crab.

The good news is, that whereas in other places where the chalk presents a major barrier to coastal progress, here at least it appeared possible to continue along the concrete path at just above sea level. Rounding the Minnis Bay headland, which in truth is Birchington-on-Sea, the cliffs loom above, though they are hardly imposing at about 50ft high. That said they do make an interesting sight as they curve in and out in tight little recessions, as if crimped in the time of giants. Whether this is a result of natural processes or human intervention it’s not clear, but either way they have more recently been tamed by man to prevent gravity pulling large chunks down on the heads of others. As the route continues towards Epple Bay the hulks of some old concrete structures, seemingly nailed to the cliffs, jut out. Military, residential, pleasure? Maybe none, or all of these. All are long since abandoned, but what purpose they may have served in their day is lost.

At this level I don’t see much of the townships beyond, but where they do appear all look much like the other and crowd round the several bays that mark this section. Epple Bay follows Minnis, then Westgate and finally St Mildred’s. At Westgate, I get told off by a woman enforcing etiquette. She’s quite right. I have strayed into a “cyclists dismount” zone without noticing any warning signs. I apologise and dismount immediately but she isn’t impressed. Just another cyclist wanker I’m sure she’s thinking. I could tell her that I’ve dismounted and pushed the bike through the three previous zones since Minnis Bay, but why should she care?

All are entirely pleasant locations with low rise housing leading away from the cliff tops (I had to come up at one point, I think just before Epple Bay), with extensive grassed areas and tree lined roads that head off into the hinterland. Each bay offers reasonable beaches and each are heaving with day-trippers, and I guess locals, enjoying the incredible weather. So, what’s not to like? Well, in fact not a lot, but I need to keep the sun in focus, and all these places face directly north. So, it’s okay now, but through November to February the sun is barely going to touch the horizon to the south, never mind kiss the beaches.

Call me a fussy old sod, but yeah, as they say, I want sun!

I’ve managed to keep a track on time and rounding a headland at Westgate, ahead is Margate, defined by its iconic solitary concrete tower block. I say iconic, but I’m guessing that there are many other descriptive words that could be used to define it.

The tower acts as a focal point, a bit like an ancient lay line, but without the ancient. I continue on the coast until just before the town centre.

I think, from the best of my memory, that I have only visited Margate twice before, though there may have been a third time. If there was the details have been deleted.

The first time was in the mid 1980’s when my then partner and I took her young nephew on the train and enjoyed a long day in the sun doing the sort of things you do. I liked it, and I liked the sandy bay when the tide was out as the sun began to set. Some years later, in the early 1990’s perhaps, another visit with at least one of my own children and extended family. Bemboms amusement park was the highlight, especially the ancient roller-coaster, though the puke inducing pirate ship ride, that I’d hoped would do the full 360 degrees up and over number, instead only rocked the victims back and forward to the heights of nausea and was enough to end the fun for me at least.

Now I think about it there must have been another time, and I think it probably was a day trip but on my own. Sometime after Benboms had closed I’m guessing. I remember how depressed Margate had become. A familiar process that was going on at many other UK resorts at that time. Most had taken a severe pounding during the 1980’s and 90’s. For every surviving chip shop and amusement arcade there was one or more empty or boarded up property with “For Sale” signs outside. Somehow, most of these resorts, and seemingly that includes Margate, have made something of a comeback, or maybe, as with Margate, some sort of reinvention (Tate that). Whatever the final tally is, and the historians have had a chance to do the maths and work out the pros and cons, an endearing memory of that time when venturing to UK coastal towns during those complex decades, was the flag of the EU flying proudly, or showing on the development notices and infrastructure schemes. I wonder what that meant in real terms? I doubt we’ll ever know. As I put on a sprint and headed up towards the station I couldn’t see any joyous outpourings of logo love for the EU now, but the tower block, which may or may not have been inhabited, bore a massive message that someone had managed to plaster on the windows of the 10th floor. A simple, unambiguous message. “B******s to Brexit.”

The tide was in at Margate but the message was clear

The tide was in at Margate but the message was clear

I’m a few minutes early for the rendezvous but my biking friends were already in situ, refreshed and raring to head off home to Deal. I’m somewhat less enthusiastic for this quick getaway, largely because I am a lesser being to my friends, who not only enjoy their cycling, but are beyond the concept of it just being a way of life. I grab an Italian lemonade and pour it down my neck. We have a good catch up natter and within 15 minutes we’re on the road and dropping back down to the seafront. Disappointingly, the tide is in.

Café to café – Thanet

Café to café – Thanet

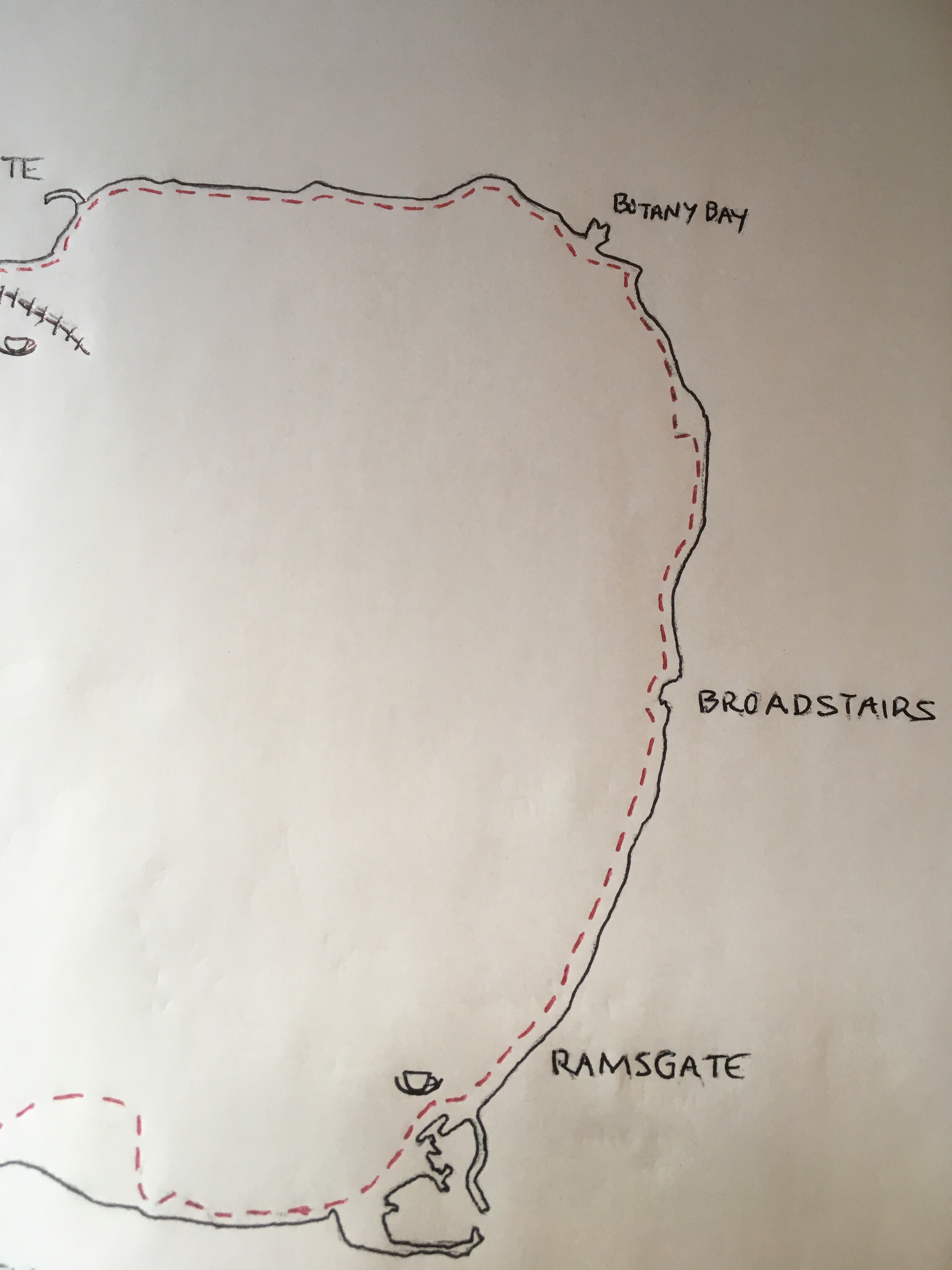

Onto Margate’s promenade and past a modern, some might suggest brutalist, building that looks like it has an industrial purpose, perhaps linked to the processing of fish. “That’s the Tate gallery,” my friends enlighten. Gosh! No time to gawp. We crack on with more crenellated chalk cliffs to our right before heading up to the top and along higher paths that begin to bear to the south-east, and with views of the English Channel opening up.

Botany Bay hove’s into view as we round a headland with an undateable flint fort of some sort in a field to our right. The cliffs are higher here and the bay itself is obscured by a chalk bastion that has been separated from the mainland and which bristles with evidence of some old industry or, more probably wartime defences. Beyond, on the next headland, and above the bay that can’t be seen, another sort of fort dominates the skyline. We close in on this rapidly as we are forced to leave the coastal path and take to a road. Passing the structure it reveals itself as an imposing Victorian pile behind high walls, with no sign to give its purpose away and so we scoot on towards, and then into, the outskirts of Broadstairs.

First line of defence – Botany Bay

First line of defence – Botany Bay

Now, whilst I had no preconceived notions of what I might discover on this second venture into the unknown, I already had some idea that whatever the north Kent coast was going to throw up, it was unlikely to grab me by the throat and say “You must live here!” And in reality that proved to be the case. All the bay towns between Minnis and Margate were, as I have said, pleasant enough, but all had the feel of day-trip destinations. Obviously a lot of people lived in and around but I didn’t feel any sense of connection. But Broadstairs? To the best of my knowledge I didn’t recall having been there but I did have some vague notion of a historical heritage. Almost certainly Dickensian.

We stuck with the road until well into the suburbs and then took a short road back to the seafront. I was keen to take some of this in but being in a three-person mini-peloton seemed to up the ante a tad, and by now we’re cracking on. I’m the least fit. In their local hands I’m bringing up the rear, following their each and every turn as we then head back into the centre of town, past a bevy of what looked like interesting pubs, and then through to the High Street. It’s possible that we passed some shops that on another day might have sparked my curiosity, but if we did they were but subliminal snapshots that time may or may not splice into my subconscious in an unguarded moment.

At the time it mattered not, but with some hindsight (this will be a reoccurring theme by the way), and following a recent visit to Tate Britain, which seems to be littered with paintings of the Kent coast, I now realise that I may have missed a trick here and if time and resources allow, a return trip maybe on the cards.

Broadstairs High Street and hanging on to the peloton by a thread.

Broadstairs High Street and hanging on to the peloton by a thread.

We continued through narrow streets and then navigated back to a road running along the cliffs with the sea now firmly to the east. A wide path separated us, across manicured grass, from the road and an eclectic range of houses with expensive sea views. The pattern continued for quite a while, and then without any particular warning, we had moved from Broadstairs into the northern suburbs of Ramsgate.

I know for certain that I have only ever been to Ramsgate once. A very long time ago, when my hair still attempted to show some interest in life, and when some bright spark at work thought it would be a good idea to drag the entire office on a long weekender to Brussels. I’ll spare you the details, and my own blushes, but the first night required a stay over in a hotel in Ramsgate before a morning boat to Dunkirk and then a dash to Brussels with just enough time to sample too much beer and then back to Blighty the next day. It was only now, as we cycled into the town, along a road that looked down onto the large harbour complex, that this life episode re-emerged into the present. A memory that most certainly would have been consigned to the “empty bin” of my mind. Anyway, as I say, I won’t elaborate, but a bit of this and that, and out popped a sort of relationship that lasted, perhaps ironically, until around the same year that the Sally Line ferries between Ramsgate and Dunkirk also severed ties.

No time though for nostalgia, but just enough time to stop in at Gerry’s Coffee House, located in a small modern square behind shops on York Street. With a lot of seafront options open to us this felt like an unlikely and unpromising spot to have the afternoon break, but my friends assured me it was for the best. And to their credit they were spot on. For one thing we were in the shade, and having been exposed since mid-morning that was no bad thing. And secondly, the staff in the café were a so solid crew. Witty, knowledgeable and it seemed just genuinely pleased to have our company. The coffee was top notch too. I almost feel a little smiley coming on at the memory 😊.

I’d like to say at this point that I was keen to crack on, but in reality, I could have easily put my feet up and called it a day. If I had been on my own I probably would have, despite the fact that, including the five miles to St Pancras in the morning, I had only covered around 30 miles so far. There was another 10 or so to go. But that would have been a dishonourable ending. In truth it wasn’t an option at all and 20 minutes after sitting down we were off again, past the extensive harbour complex which in turn gives way to a small beach, and then back up along the cliffs where again large houses, mainly detached, are set back beyond wide greensward’s. Soon we have to turn inland and through a small park which pitches you out into Pegwell. The road continues inland so there’s little sign of the coast here, but what we can’t see from the bikes is what the map will tell you is Pegwell Bay.

I mentioned earlier that I recently took a couple of hours out and visited Tate Britain, primarily to track down two pictures, “Our English Coast (Stray Sheep)” by William Holman Hunt, and “The Fighting Temeraire” by Turner (another posting, if it ever gets written). I nearly missed the Holman Hunt because it was crammed in amongst too many others in the biggest gallery in the building, and I missed the “The Fighting Temeraire” completely, because, despite the fact that Tate Britain seems to have nearly all Turners paintings, the last time they had this one was for a few months in 1987. Too bad, but what I also came across was a picture unknown to me by William Dyce called “Pegwell Bay, Kent – a Recollection of October 5th 1858.” I took a photo of it and here it is.

Pegwell Pay approx. 1858

Pegwell Pay approx. 1858

Now, that’s a less than shabby looking place don’t you agree? Fashions will have changed but that’s a spot for a morning and evening constitutional at the very least. Except, when I was looking at this picture in the gallery I was struggling to place it in any context to what I had seen on the trip. Then again, because the route had taken us away from the coast at this point, why should I have ever seen it? So, and just to satisfy my curiosity, I resorted to Google maps. And, low and behold, it seems that someone has been very busy with a bucket, spade and bulldozer!

Landfill ahoy

Landfill ahoy

Sorry, I appreciate that this is a minor and possibly irritating diversion, but this was quite a shock to me when I saw the aerial view, and although it probably makes for an interesting and no doubt diverse ecology, I think the town Council ought to have a little think about its identity and maybe re-brand as Pegwell-on-Landfill. The bay is long gone, along with the failed attempts as a tourist resort to rival Ramsgate, which unfortunately led to the initial land reclamation. And that is a shame because there is emerging evidence that the bay was the site of both the first, and then second, Roman invasions. I don’t know what old JC would make of it now, but hey, he don’t live around here no more. Oh….and just to add, the first Anglo-Saxon landings may have happened here too? That’s a lot of history to cover up but what the heck, we have to get rid of our rubbish somehow. Don’t we?

At the top of the Google image above you can see the track that took us further inland and eventually back on the coastal road above what’s left of the old hover port (I can hardly believe I’ve just used those words).

There’s no time to stop now as the last leg seems to turn into a sprint to the finish line at Deal. But Sandwich still has to be achieved and sadly there’s no coastal route here. The Sandwich road runs alongside the estuary of the River Stour (which, along with what would become the Wantsum, once formed the old sea route that separated Thanet from the mainland). Soon we are on a main road at Port Richborough which is heavily industrialised. Signposted are directions to the Roman fort of Richborough, which along with the fort at Reculver, would have controlled the southern and northern entrances to the now lost channel. At least there is a bike lane here, so some progress then. A left at a junction and we head through a modern industrial estate. Firstly some sort of dump site but then it’s high-tech, high value buildings and high as a kite chemicals. It’s called Discovery Park. There’s not much sign of a park but you can sense it’s cutting edge stuff. My friend said it reminded him of a Quatermass landscape and I could sense the abstract notion.

Soon afterwards and we’ve crossed the Stour, leaving the Isle of Thanet behind and with the old Sandwich town wall and north gate in front. Quite a contrast to what we’ve just survived at Discovery Park. I have another friend (I know, how can this be you mutter?), who would like to relocate here. He’s told me that there’s at least nine public houses (two still with bar billiard tables), a tandoori restaurant, a cricket pitch and of course the river. Yes, well, all very nice, but where’s the blinking sea? It must have been here once because why would the town be here in the first place?

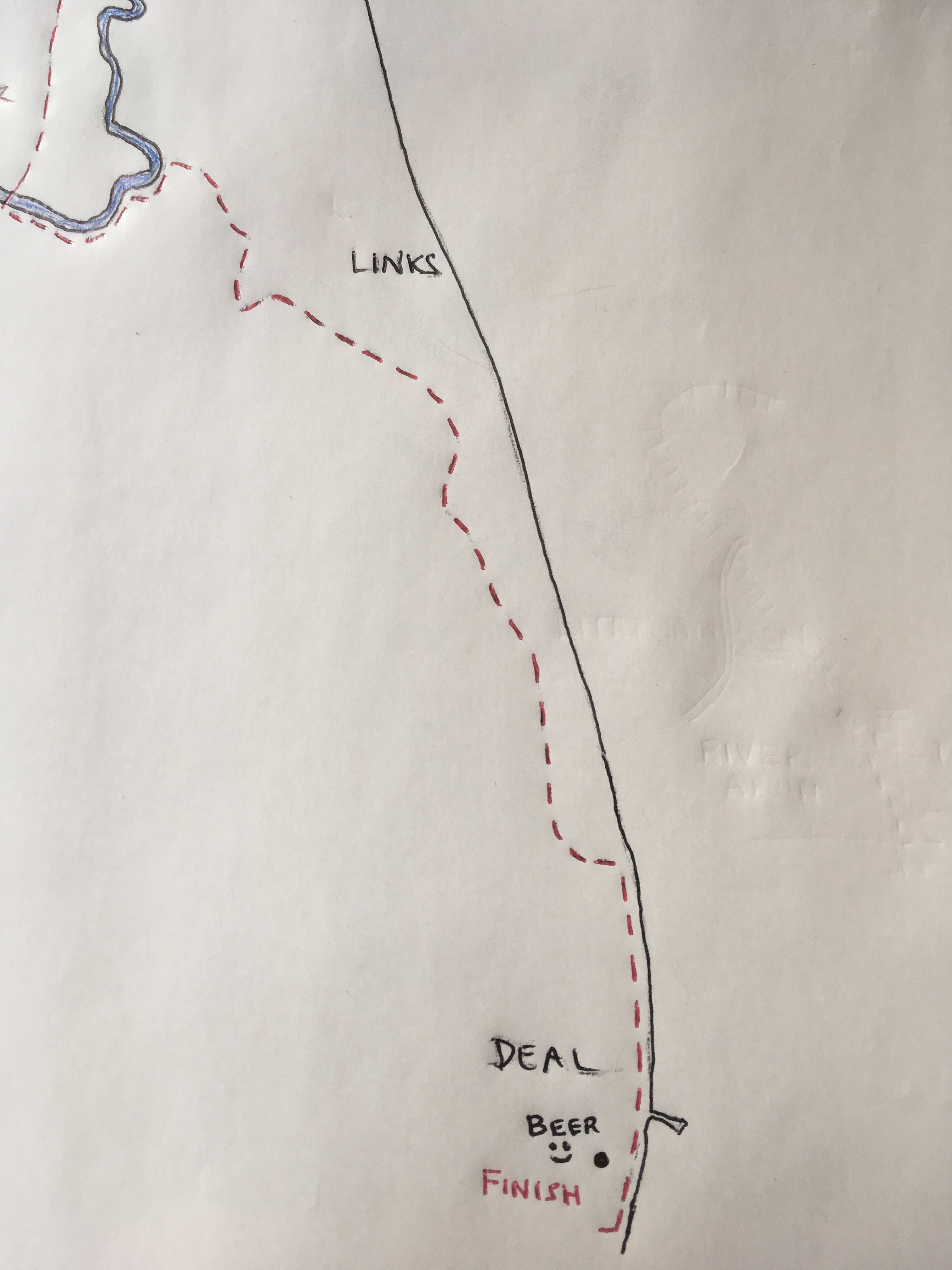

But there’s no time to investigate Sandwich further. I’ll come back another time perhaps, but for now it’s onward, down the river a short way and then along country lanes and paths that flank the famous golf course. It’s possible that there’s a coastal path we may have missed but I’m being guided by professionals and time is getting on. Nevertheless I can’t help feeling a sense of mission incomplete. Oh well, it’s all just lost Ballocks at this stage anyway.

At Sandwich Bay, with it’s handful of small houses, we are near the front again but the narrow road takes us back inland and with another golf course to our left. We’re nearly there but my energy levels are running low, despite the fact I know it’s almost over. The imaginatively named Golf Road is the back door to Deal, and after the first few houses we turn left with the sea opening up in front, and we’re now steaming along the flat beach road. It’s a beautiful evening and the French coast is carbon sharp on the horizon. Deal is different. The long strand of housing and small shops that develop as we get closer to the pier range widely in date and style. Georgian, Edwardian (but not too much) and appropriate modern. There’s nothing not to like here. It’s a place that anyone in their right mind would want to be. It is as they say “the business,” and as we group up to smash the last few yards I feel like Geraint Thomas being dragged towards the winning line by his faithful domestiques.

It’s done.

After a very quick and delightful shower that washed away the layers of sweat accrued during the long day, and then after an energising fried meal, we marched with resolute purpose to the Just Reproach (where you’ll be ejected, and even possibly arrested, for even just handling your mobile phone) for a few pints of some of the best bitter you’ll ever drink. The memory of the dreadful train journey to Herne Bay, just a few hours earlier, was extinguished. It could have been a lifetime ago. Indeed, it probably was.