In which the body and bike take a bloody hiding

OS Landranger 178

33 Miles

Rochester station, at the end of a long and unaccountably bloody day. I mulled over the following. Based on what had just happened should I, indeed could I, do Sheppey? The arguments went like this. Brambles, ash trees, stiles (lots of bloody stiles), tetanus, barbed wire, sepsis, incoming tides and an overwhelming sense of despair. Or, herons, flocks of starlings, little egrets, lapwings, nightingales, foxes, oyster catchers, curlews, kestrels (or were they harriers?), fortifications of all sorts and unparalleled views of the estuary. So, Sheppey? The prospect was that it would be more of all of the above, and really, was that what I wanted to go through again? More importantly, and maybe more relevant, what is Sheppy? Is it mainland, in which case it would need to be done? Or, and probably a winning point, is it an island?

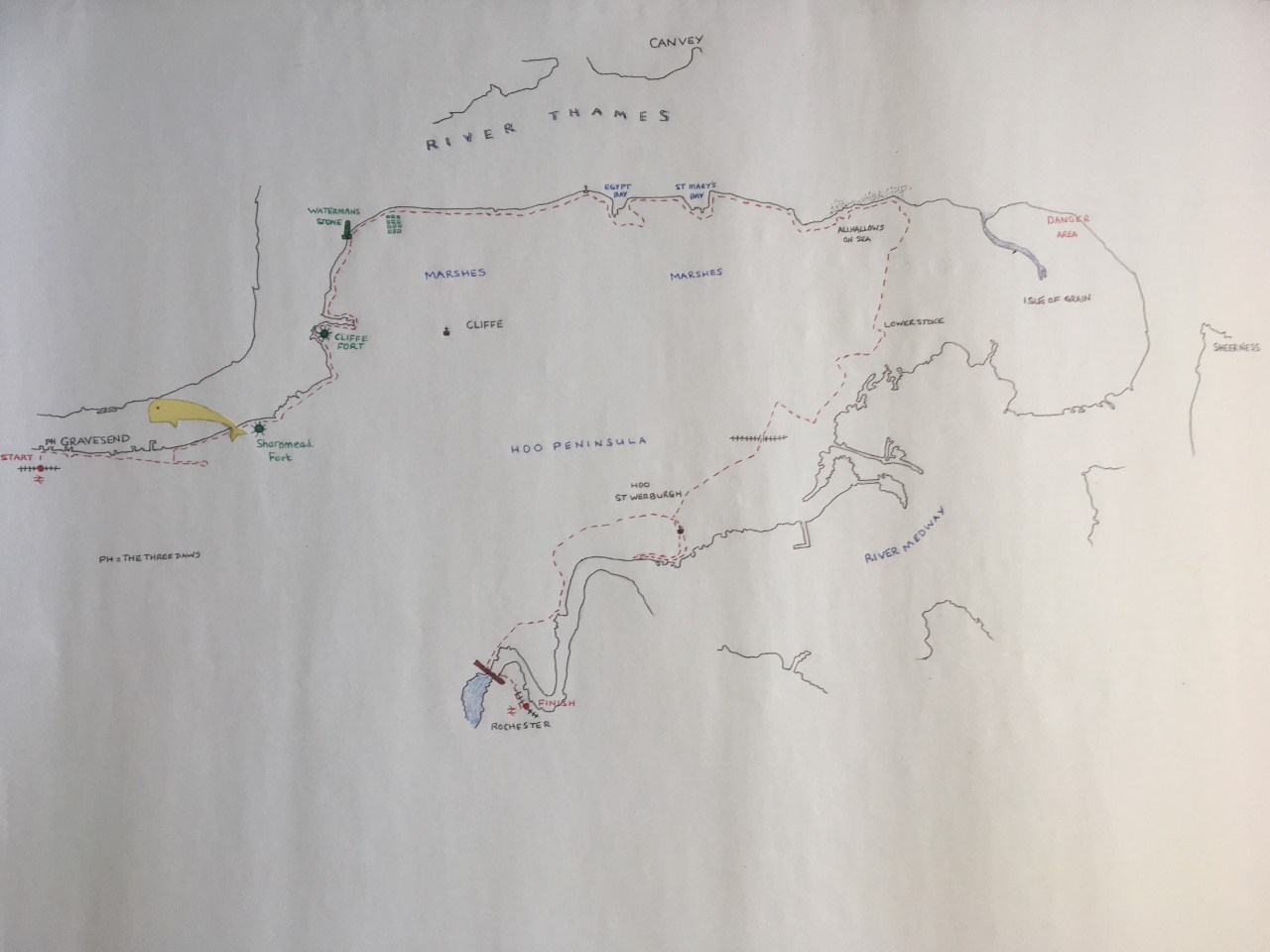

But roll back a bit, and how I had ended up at Rochester station, somewhat the worse for wear. I hadn’t been sure about this trip. I had booked the really cheap day return ticket to Rainham the evening before, with the intention of leaving the train at Gravesend, cycling the Hoo Peninsula, and getting to Rainham by the days end. Earlier on the proceeding day, and after a swim and short cycle, an instant migraine hit me at midday and my response was to sleep for three hours. Always a bit shaky after a migraine I considered the options. The weather for the 2nd October wasn’t looking great but it was going to be mild, and with a breeze from the north west. Ideal conditions maybe? I was also conscious of running out of good weather opportunities and so made the ticket purchase, rationalising that if I didn’t feel up to it the following day, what was £14 anyway? Well it’s £14 actually. Although I slept well, when I woke at 7:45 the next morning I knew I wasn’t on top form but managed to roll out of bed to make the effort. By 10:15 I was on the train to Rainham, alighting over an hour later at Gravesend to take up from where I had left off after the trip from Woolwich earlier in the summer.

Down through the jaded high street in a soft, slightly overcast light. A sign pointed to a statue of Pocahontas. It was a shame that I didn’t know, or had forgotten (or ever knew at all), the story and her association with Gravesend. It seemed an unlikely association but stranger things happened in the days of conquest. Two days before I had been looking at some photos of my granddaughter with none other than Pocahontas (well you’ll need to use some artistic licence here) at Disney World in Florida. Apparently, Pocahontas’s currency has slipped over the years and she’s no longer the big Disney hitter, now a bit of a side show compared to the stellar stars of Frozen and many of the old favourites such as Snow White and other similarly hued characters. To my shame I failed to liberate the time to divert to the statue to find out more. Instead I headed directly for the pier, where more recently a small ferry has been reintroduced that can take you to Tilbury should you chose. Though, if you were to read reviews on Trip Advisor, it sounds like you’d not want to rely on it if it was a matter of life or death, or even just for a quick coffee and cake in Essex should such things float your boat.

The journey started at the Three Daws public house (where, earlier in the summer, the trip from Woolwich had ended with a great cup of coffee in the garden). So far been travelling for over two hours and now needed a coffee before setting out. Unfortunately, the options looked limited, and being too lazy to get the padlock out and lock up the bike, I was about to set off coffee-less when a man appeared from nowhere and opened a door to the building I was standing outside, which when looking up, stated various delights, included coffee! “Err, could you do me a coffee?” I asked. He was most affable and said “of course.” Entering the shop, and leaving the bike outside with just enough of the rear wheel showing for security, I looked around and tried to understand what was going on here. Possibly internet café, certainly some items of childhood nostalgia. Not my childhood of course, but that of my kids and more recent generations. Pokémon cards for sale, Warhammer boxes, videos and DVD’s, models of this and that and all sorts of “stuff.” And a ruddy good coffee it was too but it was time to get on and exit the unique Mug and Meeple.

Past the Three Daws and dropping into a small park, snug to the river, where an old and very red lightship sits as a memory to a previous time and technology. In the park a statue and a memorial to Squadron Leader Mohinder Singh Pujji. Again, not being sure what the link was at the time, I later read that he was a renowned Sikh pilot during the war, eventually moving to east London and then Gravesend, where he died. An impressive history and someone outspoken on right wing propaganda issues such as the BNP’s use of a Spitfire as a symbol. Impressive human. Sikh and you may find.

The path then moved away from the river front for a short while, passing a small church and then dropped back to the river by the promenade which fronted onto an impressive low fort and associated earthworks, studded with various artillery pieces all pointing towards the channel (or Essex if you are paranoid and from Plaistow).

Shortly after the promenade, and quite disconcertingly, the coastal path led down a tatty lane and directly into a chaotic industrial estate. I got the feeling, from the age of the decaying buildings, that there will be a significant amount of asbestos to be removed when they are eventually demolished. Whilst the buildings were well beyond their sell buy date there was still a lot of activity. At any moment I expected a silver 1970’s Jag to screech around a corner, closely followed by a similarly aged police Rover with Jack Regan screaming “Get the slags,” to George Carter behind the steering wheel, and as they weave by at 50 miles an hour, George Cole pocks his head, and a hint of Cashmere coat, out from the panel beaters yard, looking shiftily left and right, then smiling to camera before tossing a half smoked cigar across the grease and soot covered cobbles just as the metal gate starts to close. Cue theme tune. Cycling through, and out of the estate, a police patrol car (honestly, I’m not making this up) approached from the east. “There’s nothing to see here officer,” I pondered, “…oh, except that lad over at the scrap yard, in the tank top and bell bottoms, with the Don Powell haircut and sniffing glue for lunch?”

At a cross roads beyond the industrial estate there was a plethora of confusing footpath signs. One pointed to the north and the river bank. Ok, so I explored. The road didn’t go far and ended at another industrial facility, but bank-side there was the unlikely sight of an early Victorian pub called the Ship and Lobster. It was too early for refreshments but I had a suspicion that the coast path started behind the pub. I failed to act on the suspicion and instead headed back to the crossroads, and then east along a long, straight, unmarked road with a stream and reeds to the right. Ending at a small car-park I considered the position, and concerned that I was a few hundred yards from the river, turned tail and then down a rough track that ended at the riverside walk (Saxon Shore Way). Confronted here by a heavy-duty metal gate and barrier, which in the end was a minor obstacle, as I was able to slip the bike through large apertures and skip over. So, this was the start of what was about to become a longer day than I’d expected, the barrier being a foretaste of things to come.

There were a few walkers out as I started cycling east on the rutted, but reasonably easy track that runs adjacent to the Saxon Shore Way. Mainly overcast but mild. There were small groups peppered along the sea wall with impressive looking binoculars and cameras – all looking out across the Thames. It’s the sort of activity you’d expect at a location like this, particularly if a very rare sort of Siberian wading bird had pitched up unexpectedly, but even so it was a midweek morning in early October. I almost didn’t give it any further thought, but then it dawned on me that something unusual had been happening in this part of the world over previous weeks that had made the national headlines, but had then slipped out of the limelight. There had been a Beluga whale swimming in these parts but surely it couldn’t still been there?

In fact, it was. Apparently, it had been happily wallowing around and scooping up fish for the last week or two with no signs of moving on. Maybe it had been doing the same thing I was trying and checking out places to relocate to and finding the riches of the Thames estuary to its satisfaction. Unfortunately, when I researched this a bit later, on the train back to London, I found out that the whale, which they had yet to sex, had been named Benny!!! So, whoever came up with that jazzy name (presumably the editor of the Sun), had determined, in a moment of sloppy anthropomorphic zeal, to give the poor creature a name that hasn’t been heard of or used since Crossroads. If I’m right whales are quite sophisticated creatures and can communicate across huge distances. They probably have their own names, or at least can identify themselves to each other through distinctive noises. I’m going to put this out there and suggest that far from being a “Benny,” (no disrespect to any surviving Benny’s) the Beluga is more likely to be called, within his or her natural community, something like “Click Click” or maybe “Eeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeee.” I guess it could have been worse. At least they didn’t call it Queen Elizabeth.

Easily distracted, and having not fully appreciated that if I stopped for a few minutes I might get a glimpse of the whale, I continued on and shortly pulled up at a disused structure that had clearly been a Victorian military installation of some sort.

In spite of the obvious decay it felt appropriate to have a quick gander. Despite the building’s impressive fortifications, overall it was in poor condition. Little hope, or point, in restoration, though someone with imagination could perhaps invest a pile of dosh and open up an out of the way, and out of this world, leisure, come exclusive hotel facility (just an idea), ideal maybe for whale spotting.

I wandered around for a few minutes. A male jogger showed up, and stopped to have a look around too, and then was off at faster miles an hour in the direction of Gravesend. Time to move on.

The journey continued in the same vein for another mile, with the coast facing north, and then took a turn to the left and then actually headed north, with a large body of fresh water to the right. Half way along this stretch and it became a bit messy. The path I was using below the sea wall seemed to run out but a smaller one ran on top of the earth workings. I pushed the bike up to a point with views back across mudflats and where the skeleton of a large old wooden boat lay grounded, forever, and rotting more on every tide. The “Hans Egede” was a substantial three-masted steam ship, built in 1922 in Denmark, but after a fire in 1955 was pulled from Dover, then, letting in water, came to it’s unfortunate end on this shore in 1957 (ironically just as I was starting out on my own voyage of discovery). A proper shipwreck, there are some hauntingly good photos on this link at “Derelict Places.”

https://www.derelictplaces.co.uk/main/misc-sites/34534-hans-egede-shipwreck.html#.XIOaJyj7TIV

Why won’t these bloody links work?

I continued along the narrow path where a sign, dug into the ground and in red letters, stated something to the effect that due to erosion, the path was closed. If I recall, a quite interesting range of expletives fell out into the emptiness at that moment. I won’t repeat them, but they were appropriate for the Saxon Shore Way (which seemed to have been terminated here with no obvious alternative route available). Undeterred, I peddled on cautiously, and then dismounted at the points where the path had clearly slipped into the Thames, and where some careful manoeuvring was required. Where the path was good, it was very overgrown and it was mainly a push through to the next barrier, with a more substantial Victorian fort showing to the right and behind a barbed wire fence.

The map showed this as Cliffe Fort. Substantially bigger than the last one, and in marginally better nick, though surrounded by an extraction operation of some sort that may have contributed, in part, to the path disrepair. A couple of walkers arrived at the barrier (which could have been a gate or a stile, I don’t recall) where I was resting up, taking stock and at the same time patting myself down, turning out the pannier and making a general fool of myself. Where the bloody hell were my sun-glasses? The walkers looked at a notice, similar to the one at the other end of the path and I mentioned that it was possible to get through with care. They looked at me, slightly alarmed no doubt at my antics and carried on south, a dog of some sort in tow. I should mention that it was the middle of the day, and decidedly overcast, so lacking the glasses was not an immediate concern, but, with age, my eyes have definitely become more sensitive to bright light and occasionally a glint of sun on metal, water or other reflective surface (including, annoyingly, sometimes the tiny digital tachometer display on the handlebar) can set off a migraine. Given that I had had one in the previous day, and was now some way from civilisation (okay – I know that’s a contentious statement), I was in a state of mild panic. I walked back along the path for 50 yards and nothing. Shucks, I was going to have to go on and hope for the best.

I walked back to the barrier and the bike, hoping maybe that one of the walkers would call me back and ask if some sun-glasses they had found belonged to me. It didn’t happen and I could imagine that the glasses had dropped from being hooked over my shirt and to the ground at some point when pushing past some dense vegetation.

Beyond the barrier the path wound round the side and back of the Fort, which, in its time, would have commanded an obviously strategic position on the bend of the river. The path widened but then another hurdle. This time a complex concrete thing went down, and with some sort of gap between one side and the other. Crossing required more manual handling of the bike but once on the other side I took a step back and a look at the structure. I’d seen something very similar before. At a place called Brean Down in Somerset, where another, significantly larger, Georgian/Victorian fort commands the east side of the Severn estuary. A site where, during the second big bash, an experimental land launched bouncing bomb (?) system had been built by The Ministry of Miscellaneous Experimental Weapons (not to be confused with the Ministry of Silly Walks, just in case you had, because in fact the walk along Brean Down to the Fort is neither miscellaneous nor silly and is indeed one of the very best anywhere in the west).

The structure at Cliffe Fort was a “Brennen Torpedo” launcher. Definitely not experimental and several were installed as harbour defences around the south coast at the end of the 19th Century. Never used from what I have read, but very clever I’m sure, although now of course a minor hazard. It felt like there should be a protection order on it. Maybe there is but the overall sense of decay around the site suggested that it was an area which the authorities might prefer to ignore and hope the sea will, in due course, wash away.

Beyond the torpedo launcher, and immediately I was confronted by the full impact of the aggregate harvesting that was going on here. Low mountains of gravel, metal structures, rubber belts, machinery, jetties and high fencing. The fort may never have seen any major action in its time but there was no doubt it was now under siege from a different enemy. Whoever controlled this site now viewed the ancient structure as nothing more than a major pain in the arse, and had gone to every length possible to deter stray walkers (and certainly cyclist). I walked round the site and then to the entrance of a creek at the north. A path headed inland, following the side of the creek. I remounted the bike and hoped for speedy progress now that the fort had been circumnavigated. About 100 meters on, and in a dense low wooded area (silver birch I think), and the path started to divide and head off deeper into the thickets. It looked a bit like a multiple-choice puzzle. Which path to certain death? Which to salvation? Which to uncertainty? I went for the one closest to the creek. That seemed logical enough. Except, after another 20 or 30 meters the branches started to close in, to the point where it was hard to cycle, and then not cycle at all. Okay, I had taken the wrong path. So what? Back to the junction. I took the one to the right, guessing that it would link up with the dusty road that led to the gravel pit. Nope! Same problem. Back again and the middle route next. So…that got me about 10 meters and the same problem. Bollocks!!!!!

Back at the junction there was only one decision to be made. Go back, or bang on? I decided to bang on and went back to the first route that hugged the creek wall. For a little bit it was possible to turn the peddles and scrape through rough undergrowth but within seconds the encroaching foliage from the young trees made the task less attractive, and dismounting I began to push through. Familiar! The track was certainly visible, not least because it was running close to the low concrete sea wall, and so navigating wasn’t an issue, but with every meter the attritional impact was increasing, made worse by the pannier appendage which snagged on every branch. The pannier contained the usual unnecessary crap, various weighty tools that you are convinced will serve some sort of important purpose, but never actually do, the bloody padlock weighing half a tonne, map, portable battery charger that never gets used but you know one day will save your life, layers of clothing that were discarded through the day (or are just there for later if you need them), and of course a plastic box with two rolls (peanut butter if I recall on this occasion). But, missing, and for good reason as I was in north Kent, and I suspect there are some quite hefty penalties in these parts, a machete. Of all the things I could have done with as painful progress was made, a machete would have solved a lot of problems. Instead, the branches, all angled and aggressive and at every height, snagged on peddles, legs, chain and gears, shoulders, ears and brake pads. All there was to do was push, grin and grown. Oh, I groaned. Particularly as there was no light at the end of the tunnel. After maybe five minutes, and with some final damaging shoves, the bike and I were free of the worst of it and I was able to cycle on round to the end of the creek and back to the wide track along the foot of the sea wall to the left, with marshland to the right. I stopped and considered how the two women with the dog at the fort had made it through from the other end. They didn’t look as if they’d been through the mill and out the other side. There must have been another route, but I wasn’t going back to find it now.

I stopped as a walker approached. We chatted for a minute about the weather and why on earth either of us were here at all. He was from the area but had moved away when he was a child, and was revisiting for the first time to see it again. I don’t think it was said, but I believe there was a tacit acknowledgement that we had both been lured here under false intent, and that as desperate places go, this was just about it.

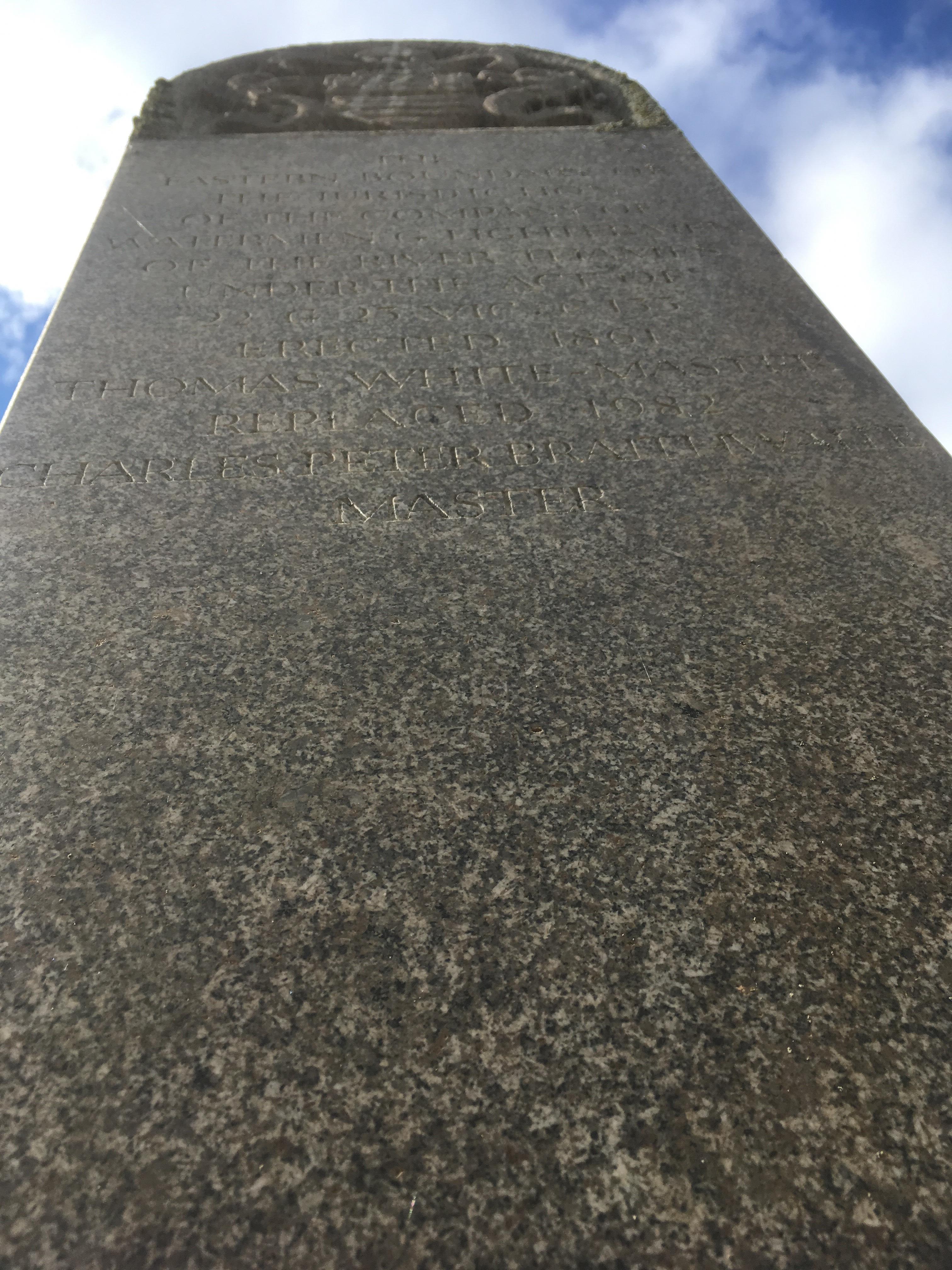

Pressing on and along the other side of the creek, the track headed north and then slowly swept back to the east. The next stop, and feature, came in due course at Lower Hope Point. Nothing impressive it has to be said, but a stone monument, maybe about 8 feet high and set next to the sea wall. This was Watermans Stone which marks the eastern limit to the licence granted to Thames Watermen and Lightermen (people licenced by the Port of London Authority to work boats in case that’s not too clear). I climbed the steep bank to the sea wall to take a closer look and took the inadequate photo below that somehow makes it look monumental in scale. It’s not. It’s a lonely spot.

Moving on and the path continued to run below the high earth banking with the sea wall on top and marshes to the right. A short hop on and within the marshes some structures emerge. Regularly spaced. Concrete, rectangular and roofless and each set apart from the next by rough pasture. If not houses for pigs (not a Kent thing from what I’ve seen), then almost certainly military. Despite the remoteness of the location this had once been the site of a thriving explosives works, built in the late 19th century and subsequently closed once the need to kill millions of people in Europe declined after 1918.

Being slightly elevated on the path above this area, I counted maybe 12 of these structures, and some other structures further away which were obviously connected to the site. The best way to get a fuller understanding of the scale of the operation can only be fully grasped from Google maps. It’s enormous, and in some strange way, enchanting. If you were to see similar features from the air, in say Mexico or Peru, you would almost certainly conclude that they were ancient, mystical and vital. I don’t know what happened to Erich Von Daniken, or if indeed he’s still going strong. Back in the day (ancient history), and if presented with these images and told that they were from some obscure part of central America, a whole books worth of material would have emerged and sold millions to vulnerable teenagers (and some people who live in Cornwall), on claims that each of the visible oblong earth works could have been alien baby incubation pods. Well, enchanting or not, when things went wrong here (and they did), people died.

Surrounded by history, despite being nowhere, it was a fascinating area. And on doing some research after the event, what I found most extraordinary was that for some decades in the early 19th century, some entrepreneurial spirits operated a beer house, either next to the fort or near the Waterman’s stone called the Hope and Anchor (it’s not entirely clear from the on-line documentation exactly where, although near the Waterman’s stone is most likely). The pub had closed by the time the explosives works opened, which was almost certainly a blessing in disguise when you think about it, but the fact that anyone would venture out this far to try and make a living selling beer to people working on the margins does beggar belief. After it closed down it seems to have been replaced by a country house. There’s no obvious sign of that now either.

As I circumnavigated this section, continually looking across the marshes and trying to understand more about these strange structures, a kestrel (or similar) rose out of the grasses and soared above me and then wheeled northwards, settling on a fence post a fifty yards on. Stop bike and scrabble for camera with long lens. Lens cap off, point in general direction, locate objective, press button. Humph! Forgot to turn camera on. Turn camera on – point again. Too late. Bugger! Or, the flip side – I just saved myself 50p in development charges. There was a lot of bird life around these parts. Herons stalking drainage streams, black and white sea birds with red bills that I think were Oyster-catchers, or sandpipers but which I always call curlews or lapwings, and lapwings and curlews certainly (or were they oyster-catchers or sandpipers?). Observed fauna aside I came to a point where some basics had to be overcome and where the field and path was abruptly bisected by a boundary fence, a gate and a stile. Quickly traversed I continued on.

Despite the diversity of bird life that, with the exception on the herons, I’d rarely see in London, what I then saw was up there on the wildlife spotting charts. As I continued along the path, that had diverged slightly away from the coastal defences, and looking directly ahead, from out of the long grass next to the drainage ditch, a fox, breaking cover. Large and magnificently pelted, it stood stock still on the path about 30 yards from me. I slowed down and half thought about going through the camera shenanigans again, but despite what I thought was a stealthy approach, suddenly the fox picked up on my presence. Strangely, instead of slipping back into cover, it took off at pace directly along the path and away from me for about another 50 or so yards before then disappearing. Whilst it was on the path, I followed. I have foxes coming out of my ears where I live in the metropolis. They are in and out my small garden all year round, and sometimes I’ve sat in the sun whilst young cubs have sat or played near my chair. When I’ve told people I know, who have their feet in the country, they can’t believe it and say they almost never see wild foxes. So, despite the fact that my urban north London foxes are great entertainment on an almost daily basis, actually seeing one close up and running at full tilt in a more natural habitat, was jaw dropping. Why anyone in this day and age would want to inflict gruesome death on one simply doesn’t comprehend. I am of course very aware that this is a nimby view of country life, but there it is. We can all do a bit better if we try.

Past the point where the fox had slipped away, the track began to turn to the right and came to a full stop at a second fence and low stile. No big deal other than dismounting, throwing the pannier over, and then clutching and manhandling the bike to the other side. I remounted and carried on, this time on the top of the earth banking, which for the first time allowed a good view of the river and towards the refineries on Canvey Island. My phone rang. It surprised me. I am sure it wouldn’t have been too long ago that finding a signal in these parts would have required climbing a tree (of which there was none) or risking a pylon. It was my son, just a social chat. Welcomed. It was a great reason to stop and have a rest. By the end of the conversation, where I’d explained where I was, I am pretty sure he was convinced I had lost my mind. After the call I lay down in the warmth, drinking some water and tucking into a roll. Everything was good although I couldn’t avoid the occasional glance down at my legs which had clearly taken a lashing during the forced push through the thickets back at the fort.

Back on the bike and with a new spring in my calves. Until, almost straight away, a third fence and stile. Shucks….was not what I thought. But hey ho, all part of the test. Repeat routine.

After this the track, more of a rough road now, headed south inland and then around some marshland/salt flats, which was access restricted. Another couple of minutes and with this area navigated, and back by the river with Egypt Bay coming into view, unexpected signs of white sand beach creeping above the mad flats and below the marsh. But then another stile. This was beginning to get a little tedious, but hope springs eternal of course and maybe that would be the last? Except, within a few seconds of the remount and forward movement, there was another one, and I wasn’t even round the small bay. Okay, so this was a complex piece of landscape, and maybe once past, the path would open up again.

It’s possible that there was another one before the end of Egypt Bay, but back on the track and heading directly east, making out Southend over the water (east by north east), shafts of sunlight picking out recognisable features. And then, oh lorks, yet another stile. I was losing count, and beginning to lose the will. Over again, and further on to a second bay. St Mary’s Bay was slightly bigger that Egypt and sported two sparkling beaches, one to the west, and one to east. Small but nevertheless remarkable given the location. If time had stopped maybe I would have too. Despite the allure of the pocket beaches I figured that, with the day now warming up quickly (as the sun started to find more breaks in the low cloud), along with the marsh and washed up seaweed, my exposed skin would be an instant magnet to every marginalised fly between Cliffe and Allhallows, which I could now see a mile or so ahead and which had become the object of immediate desire. Ah, and I forgot to mention, there was another bloody stile to be mounted. The tedium of it all!

Rounding the eastern tip of the bay and now it was clearly just a short hop and I’d be swigging a coke outside a café or pub at Allhallows on Sea. Sweet!

On the marshes to the right, and more of the small constructions that I’d seen earlier. Less than before but still of interest. Certainly, more interesting than the next barrier and stile, which was surely to be the last?

By now I had discovered that there were countless ways to lift the bike over these hideous intrusions, not least because each stile was different to the last. High, low, one step, two steps, wobbly or straight or angled or wreathed in brambles or barbed wire, or just broken and indecipherable. Unfortunately, on each encounter I instantaneously forget about any previously learned techniques and remorselessly (that should read dumbly) sallied forth with sluggish abandon to another unknown outcome. This bonehead approach invariably resulted in some twisted outcome for the bike and either a sharp wrap on the knuckles or ribs from the handles and other sharp bits and pieces attached, or a swipe of the left peddle across one or either shin. But the reward was just a few hundred meters away. In sight and touching distance. Even if there was one more stile to conquer, I had hope on my shoulders and the wings of Icarus to carry me forward.

Before Allhallows could be reached there was another sweep in the coastline. Not quite a bay but another sandy beach. At this point the path headed south and away from the sea. There may have been yet another stile, but frankly by now I had lost count. A decision was needed. The path looked like it was going to continue leading inland. I stopped and got out the OS map. Confirmation that the track led on up the contours and to a road set back a kilometre or so from the coast. That would have been easy I guess but given that the map also showed a footpath option across the marsh to the left, and the guiding principles of the trip requiring a notional adherence to the coastline, I lost sight of the better judgement call, and where a wooden sign indicated the path across the marsh I took the plunge.

There was absolutely no question of being able to cycle this stretch (although I gave it a go). The path was fairly clear on the ground, but it was flanked on both sides by head high reeds closing in and around, and frequent dips and mounds that wound across the rough land flanking a tidal stream. Rough going but progressing. That was the main thing. Towards the end of this short section the path improved a bit so I was able to cycle a short distance before once again the path turned sharply inland, and now with another stream to the left. If there had been a way to get across this new stream at this point, I would have taken it, but if it existed at all I must have missed the opportunity because now I was pushing the bike across a thin and worryingly fragile old railway sleeper that bridged another stream. And then the path came to an abrupt end. A barrier of trees, brambles and undefined bushes. I think maybe at this point my orienteering skills, honed as a youth, let me down. I could see the remnants of a sign that had all the indications of a directional footpath indicator. The indication was that the path led through the woods. And it did indeed. It was just about visible in the gloom, except that whoever had last used it must have been done so in the previous century, and then failed to pass the knowledge on to the next generation.

And so, for the second time in the day, I worked up the resolve and began to shove.

A bit like an abusive relationship, which you repeatedly return to. You recognise that you’ve been in a similar situation before, in fact many times, and on this day bizarrely just an hour or two earlier. After each occasion you hold it firmly in the mind that you’ve learned an important lesson and won’t make the same mistakes again. But there it is again. There are some little alerts fizzing through the brain. Stop, and perhaps think about your position. Is it really a good idea to plough on at this point? What if, instead, you just back out and head for that road showing on the map? What if? But these alerts. What exactly are they? They’re saboteurs. Tricksters. Agent provocateurs. Derailleurs. And they’re not going to prevail because you’ve convinced yourself that you’re still in control. And so, forward you go again, slowly sucking into the web, or perhaps like an insect intoxicated by the fragrance exuding from a Venus flytrap you push (literally) on to an unknown place where an almost inevitable outcome awaits. Whereas the thickets around the fort were an irritating challenge, this coppice, not showing on the OS map, had been growing for considerably longer, and almost formed a solid wall of trunks and branches. As leaves, twigs and all sorts of pointy bits snapped and thrashed back at my limited forward momentum (every action has a….huh, you know, sort of thing going on), I regretted not having the sun glasses and a helmet for upper body protection. It took some minutes to go perhaps 20 yards, and I had certainly taken some damage.

After clearing the thicket and checking that all-important parts of the bike still functioned (and frankly amazed that they did), I looked up to assess the terrain ahead. And what precisely was ahead? Almost immediately….yet another sodding stile leading to a large field. The field wasn’t showing on the map either, but from how I read it, a short path would go through the field and then it would track back north where the path would cross over the barrier stream. Well, on the basis of the map, and that one stile must inevitably lead to another, I was now in auto-pilot mode. The well worked routine again. Throw the pannier over first and hope it doesn’t land on a cow pat. Gird yourself (check if “gird” is a word) and grip right hand to the rear angled upright. Lift left hand. Try and remember what it’s supposed to grip. Grab random part of the front of bike and lift. Feeling confident I placed my left foot on the lower step and raised the right foot to the top step. So far so good. I hadn’t fainted. Commence forward momentum with right foot looping over the horizontal wooden beam. Touchdown achieved. Left foot comes up to top step and more forward momentum. Against the trend I seemed to have achieved a comfortable position, and letting the bike descend forward, I was quietly confident that the front wheel would touch soil without further incident. Still holding on with my right hand gently lowering the back wheel of the bike, but also in the process of hopping down too, when there’s a sharp tearing sensation to the inside of the left arm (which had done its part of the job and was now liberated, and for a very brief moment, free from all alarm). I’m just too tired to scream or fuss. I could see the alloy clean barb on the wire that had opened up what looked like a small shark’s tooth bite an inch or so from a major artery, and now issued a steady trickle of the red stuff. Suck hard. Walk on. Suck hard. Walk, and so on, and shortly I’m half way across the foot of the field and slowly waking up to the fact that, so far, I’ve not seen another stile, whilst at the same time mulling over the various infections I may have acquired in the last minute, including tetanus, sepsis and hadmycountrifillius (which I experience occasionally ever since getting a dose in my early twenties whilst on a disastrous outing in the Peak District – it can’t be treated although medical advice remains that if you have had this once, avoid leaving urban centres at all costs).

I reached the far end of the pasture field without any sign of an escape route. Looking up the hill and at the top was a large farmhouse with dominant views. That view, at that moment, would have included a sight for sore eyes. A “towny,” out of town and out of his depth. The map didn’t help and neither did the Google map (which, once loaded up, compounded the realisation that I was well and truly in the thick of it). I tried not to think about the farmer up at the house with his 12-bore, currently trained in my general direction.

It was also getting on. The prospect of having to go back over the stile with its deadly wire, and then back through the jungle, had zero appeal but I recognised that it might be the only choice. I cycled back along the bottom of the field, which was lined by a barbed wire fence, and nothing to hope for. I was back at the stile and had almost worked up the courage to go back over when I decided (probably some irrational sense of hope), to have one last look, and so set off again along the bottom of the field, more slowly and trying to pay closer attention.

And there, about half way across the field, something I had missed on the two previous peddle pasts. Not a stile (though there should have been, now probably lost to nature), but one small top strand of barbed wire that was missing between two posts. Beyond a steep drop down a bank that ended at the stream, and beyond another bank leading up to, and back to the salt marsh.

So, by now I know you’ve had enough of this torturous tale, that may or may not be fiction, or at best a questionable reality. I apologise but I can guess you have worked out the next bit already. Off came the pannier, and to avoid catastrophe I placed it with the greatest of care over the lower wire and settled it safely in some long grass. Mounting the bike, I wheeled round and back into the field, slowly climbing up the rough grassy terrain. At about 20 yards, I turned, assessing and finding an angle to the fence. Then, with an adrenaline fuelled push on the peddles, I set off at speed back down the hill. On hitting a humped, slightly ramped patch of grassy knoll, and at the same time pulling back on the handle bars, the bike launched upwards, clearing the barbs below, and then with a crash I was over the stream and laying on the ground under the bike on soft moss and grass and eternally grateful to having watched the Great Escape enough times to understand the dynamics. Unlike our Boxing Day hero, I actually achieved the jump, not ending up entangled and hopeless on the wire.

I retrieved the pannier and picked up the bike, grateful for no further injury. What was before me was the barren, and slowly submerging tidal flats. There was no prospect of cycling this rugged terrain. As I started the last push, I pondered on the last few minutes. I wondered whether it would have really been possible to leap over the fence and the stream on the bike? I thought that perhaps it was possible (just watch some of those nutters doing the downhill biking in Valparaiso, Chile, on uTube), but not by me. Not me this time. Sometimes life is not as strange as fiction. Oh, come on, what were you thinking? I’m not Steve McQueen FFS!

The thin zone of what I guess could be described as salt flats, was a small environmental ecosystem. Low, dark green vegetation, which flared red and orange hues in places, and clung to the hard-sandy soil. A path of sorts existed but twisted in and out of narrow muddy inlets that, to some mild alarm, were beginning to fill up as the tide swept in off the river. I reached the point where the land met the sea. Slightly undefined but tangible. The remaining mud flats were disappearing in front of my eyes, but to the east, some 200 meters or so out, the roof of an old concrete pill box, the structure at an unnatural angle and being consumed quickly in an inevitable oblivion. Its distance from the land and rapid submersion said something about the coastal erosion in the area since the War.

A bit further on and another pill-box, closer to the land, but still out of its depth and with a drunken lean to the north. On the flats around the structure, and just before the water consumed, a hundred lapwings, or peewits, or whatever? Out came the camera. Well – you know the rest. It could have been a great photo.

A third pill box, again slowly losing interest in its original purpose, was observed half way up one of the fields behind the marshes, a final line of defence before the hinterland. Along with many of the other military structures along this part of the coast they never saw action, and in a way, that was a positive perhaps.

Continuing on across this broken landscape, almost lunar (apart from the water and shrubs), I could see the first buildings of Allhallows approaching quickly. But worryingly not quick enough, as every few meters there would be a stream with huge quantities of sea water piling inland, and leading to several diversions in and out of the flats. On a couple of occasions there was no option but to skip across the water and hope for the best. An intoxicating environment. Alone at the edge. The last human I had seen was the walking man before Waterman’s Stone. Surely one of the most remote spots on the entire UK coast. But getting late.

By the time I have reached the end of the “beach” I’m a minor study in sacrifice. If there was a place in Allhallows to buy refreshments I was sure to be probed on my lacerations and would be hard pressed to explain them without being considered a suspect in something.

A low bank was the last hurdle. A last heave up the bank and a garden to a large bungalow lay ahead, where a group of people sat enjoying the sun at the end of the day. I didn’t look but have little doubt they would have been a tad surprised at the sight of an old man with a bike suddenly rearing from the marshes in quite such a fashion and at such a time of day. I was in no doubt that only a small handful of people would have ever undertaken this section on a bike. And I’m not saying that this was some sort of heroic achievement. It certainly wasn’t. Foolish and unnecessary to be sure.

At the top of the bank a metal sign on a post warning of the dangers of the tides. Who would have guessed? The sign was peppered with gunshot, as you tend to get at places on the margin. A very popular activity with separatist groups in places like Corsica, for instance. I wasn’t aware that there was a separatist Hoo Peninsula group (HOOPLA to those in the know), but who’s to say there wasn’t, and that they didn’t have a valid cause? If there is such a group, I’m pretty sure they are young, idealistic, and pissed out of their heads on a Friday night on cheap cider and with an air-gun to ward off the boredom. I know……I once was.

At last, back on the saddle and cruising along the pleasant frontage at Allhallows on Sea. The tide was, by now, pretty much in, so it wasn’t possible to tell if there was a sandy beach. I think though that there might have been. A series of groynes – maybe the first I’d seen on this section out of London. The area behind the front was a very large static home holiday resort, maintained and manicured to a very high standard. This was a nice place, with expansive views across the estuary. It seemed to have all the trimmings. I wondered if you could think of it as the first “resort” east of London on the Kent coast? Although it was a Tuesday in early October there was a lot of activity with vehicles and people buzzing around. Yes, yes, yes, I had to get on and leave these contented soles to their perfect isolation and their autumn almanacs.

Up through the resort, that went on for about half a mile, and then into the real Allhallows. Nothing much to comment on other than I did run the risk of curious enquiries, bite the bullet and went onto a small shop and bought a coke, consumed too quickly outside.

The shop was on a road through an estate which headed east, and back to the coast past the holiday park. Sometimes you just have to make the most practical decision available. I’d been lacerated, thrashed and spiked too much already, and with around 12 stiles already under my belt, the idea of taking on some more miles of self-flagellation at this time of the day didn’t even enter my head. Anyway, I had spent some time earlier in the day looking at the options in this area, and frankly it wasn’t going to happen. The Isle of Grain, for that was it, sits beyond the Allhallows area and separated by a winding river that the map showed would require at least another hours flaffing about, and with no definite certainty of a crossing. Even if a crossing had been possible, the area at the north eastern tip shows as out of bounds (explosive to be precise), and then there is Grain itself, which other than a small community, is one huge petrochemical site. I know this because I once drove from London on a wet November day many years ago to find out for myself. Don’t ask! The rest of the coast at Grain, on the west bank of the Medway estuary, shows as a confusing mess of tidal flats and complex creeks. Definitely a big miss.

And so, I rode south, up and out of Allhallows, then at a higher elevation between fields towards the village of Stoke. The late afternoon sun had broken through. The view towards Grain, the Medway estuary and beyond was epic. All blue sky and vapour trails.

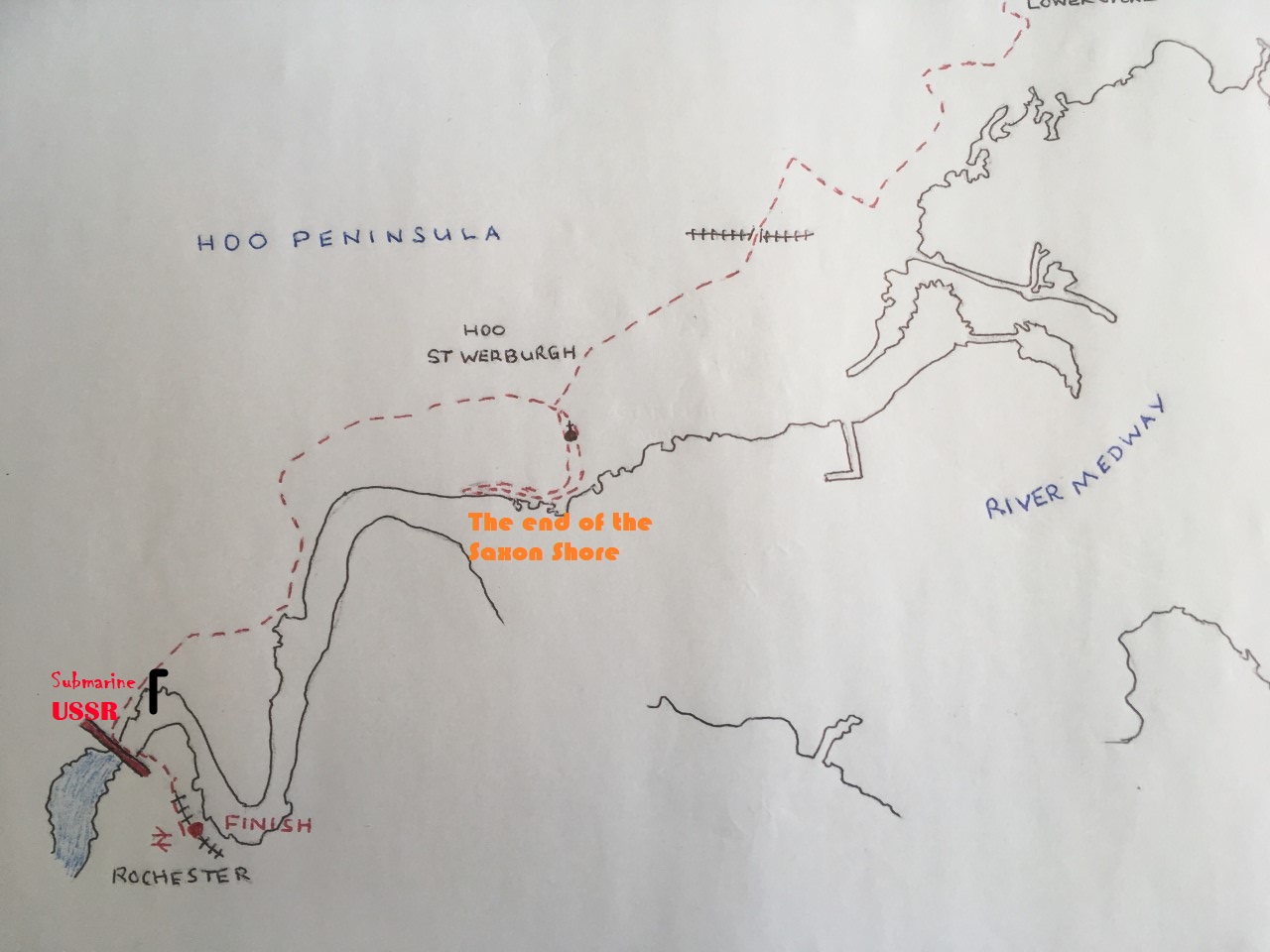

Down into Stoke, a left, through the village and then a right onto Grain Road and then the A228 west bound again. Any thoughts of reaching Rainham were now completely banished, and so the new, less ambitious target station was Rochester. A constant flow of traffic was coming out of Grain and with safety in mind I then took a left down a quieter road to Upper Stoke. Through Upper Stoke and then along a road, surrounded by fields which ran closer again to the river. A turn to the right, up a hill, along a top and then back down and over a single-track railway that seemed to serve the industrial hubs. A roundabout and then more fields and finally into the small town of Hoo St Werburgh. At a junction near the centre I turned left, headed south to an imposing church, passed through the graveyard and continued for a short while until reaching the banks of the Medway for the first time. The OS map showed that the path now followed the bank of the river for the rest of the journey, and that didn’t look too far at all, which was a relief as the early signs of dusk were gathering.

The track reached a gate, which, once past, gave access to a large local Marina. Through the Marina and then another gate and the path continued past some woods. Quite a contrast to the terrain so far, but it wasn’t going to last. A man walking a dog passed by as the track became more uneven near the river bank. And then, about 50 meters on, with the new residential developments of Chatham showing on the opposite shore, a crumbling Victorian redbrick wall (no doubt some old fort or other) appeared by the path, but which, along with the path, became submerged by the rising tide. And I knew my luck was out.

And so, with no path to continue, it was back to Hoo St Werburgh, up via a rambling holiday home site, past the church again, onto the main road. Then along the main A228 and down into first Lower, and then Upper Upnor. A track and then a footpath flanked the western approach road to the Medway tunnel to the left. Then a roundabout, and another track over a low ridge with industry in view at all times, and finally down again to the river, with Rochester Castle, its bridges, and an old, rather sad looking cold war type submarine on display. I wasn’t hanging around to enjoy the view though, and a further short section alongside the river, with development work all around, and I was then on the road bridge, across the Medway and soon afterwards at the station.

Rochester Station is a modern affair, and after grabbing a coffee, and looking at the digital display, I worked out that the next train on which my ticket would be valid was at least another half hour down the track. There was an alternative though. To be fair, it wasn’t exactly legal, but I was prepared to take the chance. A Javelin was due in any minute! Sod the ticket….St Pancras was screaming at me to come back. And as I waited, I mulled. Sheppey?

I boarded the fast train and took up residency in my usual place next to the toilet. Looking down and the evidence of destruction was very obvious. The final scores:

- Left leg = bloody scabs times two.

- Right leg = bloody scabs times five (and how did I mash up the knee?)

- And both lashed to shreds

- Runner up – inside left arm = deep gash just to the right of major artery

At St Pancras, and in a scene that again bore an uncomfortable similarity to the Great Escape, I alighted the train and headed towards the control barriers. An unusually high number of uniformed staff were lined up behind the gates. I was resigned to discovery. But I already had my story worked out. It was just going to be the truth, and hope that some sympathy would see me through any closer interrogation. As back-up I had done little to clean up the bloody legs.

As I pulled out the invalid ticket, knowing full well my fate, I noticed that at a barrier to the right a woman, weighted down with bags and too many items of clothing, was having some difficulty trying to push her ticket through the slot. A staff member was assisting, and after a couple more attempts the member of staff gave up the challenge and checked the woman through. And so, spotting what appeared to be a weak link in the system, and in my best Dickie Attenborough, I approached the same barrier announcing confidently, and with a jolly smile on my face, that I suspected my ticket would present similar issues, and without further challenge I was sprung through!

No looking back.

Some weeks on, in the midst of winter and with more time to research some of the high, and decidedly low, points of the day, I came across a blog by a chap who had walked much of the same route in 2002. I had of course by now fully recovered, mentally and physically, from the Hoo trauma, and had pretty much got a grip on the things I had encountered during the journey, so when I started to read this man’s account of his own miserable experience (including an almost identical sense of lost desolation on the salt flats outside Allhallows) what could I do but laugh.

The link to the blog (sorry but I don’t seem to have worked out yet how to make these links interactive – help anyone?) is below, but just as a taster I quote:

“Every little thing that happened today added to my increasing ill temper – the path not being walkable, the batteries on my mobile running out, even Sam phoning me up. All in all it was the first total joyless day of the trip so far, a real downer.”

http://www.britishwalks.org/walks/2002/286.php

Sheppey – That’s an island…right?

One thought on “Gravesend to Rochester via the Hoo Peninsular – 2nd October 2018”