Landrangers 199 and 189

65 miles

A week to the day after the north Kent debacle, during which I found out as much as I will ever need to know about stiles. The left shin still carried a significant crusty scar which required careful sock fitting to avoid a painful scrape and reopening the wound, but undeterred I had bought an online ticket the previous night and was then on my way from Victoria to Eastbourne. I had opted not to take the proffered option of a toilet seat. I was pretty sure that I was going to end up there anyway and certainly had no intention of paying a bit extra for the privilege. (There’s a very poor pun lurking here, but despite a number of reworkings, editorial control has kicked in and the reader has been spared).

I wasn’t too sure how far the intended route would be but had spent a few minutes on Google checking out the options and shockingly, and to my disbelief, the number of miles thrown up seemed so unlikely I instantly dismissed them. In hindsight, maybe I should have paid more attention. Along with the 8 miles from home to Victoria this was about to be the longest day. Fortunately, for any reader, it maybe some consolation to know in advance that due to a relative absence of excitement this may end up as the shortest account. Assuming, of course, that my brain avoids too many tangential hijacks.

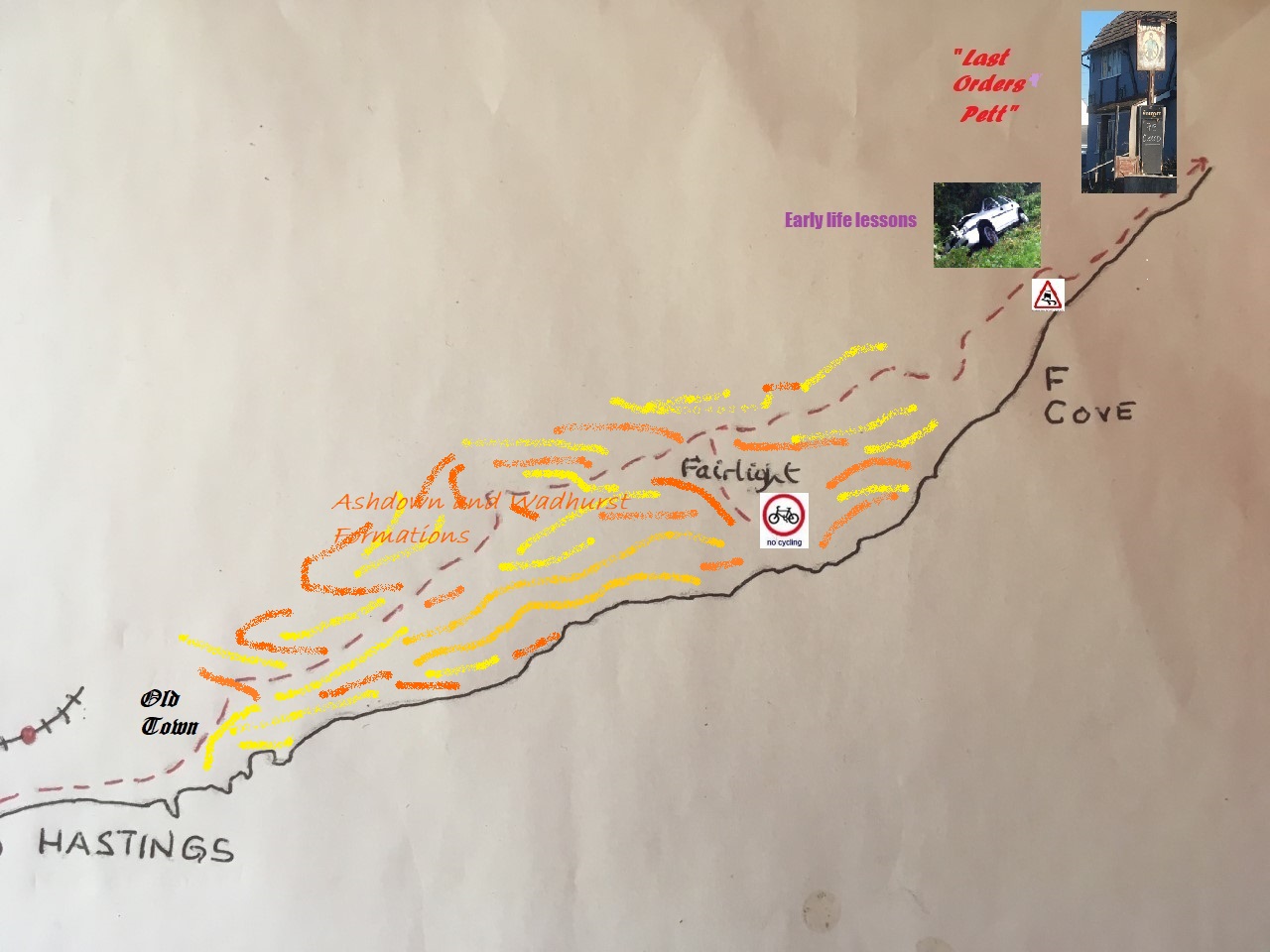

With some unexpected foresight I’d had a root around some book-shelves and dug out an old Landranger OS map that covered the first part of the journey between Eastbourne and Hastings – Crown Copyright 1992 – a time when I was in my mid 30’s. Reason for original purchase completely unknown. The cover has an image of four modes of transport, a car, a camper van, a jogger and, encouragingly, a cyclist. So, (perhaps with the emergence of Chris Boardman and others) some sort of early recognition, that cycling was maybe a funky thing – worthy of some iconography. Regrettably the map must have pre-dated Sustran and the national bike routes, because despite the teaser on the cover, any suggestion that the map-makers were in possession of any information useful to cyclists ranged from scant to zero.

But, hey ho, this wasn’t going to be an exercise in navigational expertise. The route looked pretty straight forward. West to east, mainly along the coast roads and proms, with some minor diversions inland, but nothing to be alarmed about.

After leaving the station, having completed the pleasant trip from Victoria, it was as simple as down to the pier, and left along the Royal Parade with Eastbourne’s own Napoleonic Redoubt guarding the coast. Naturally, and despite the drift into autumn, the sun was blazing, and a gentle breeze came up from the south-west. As I set off, behind me Beachy Head and the Seven Sisters chalk massif, where some weeks earlier I had heaved, dragged and pushed the bike up and down the combes and clines. The Channel a millpond. Having carried out a brief recce of the maps on the train (I also had a much more up to date Landranger map for the second part of the journey), I knew that after a mile or two I would come to an epic expanse of wasteland called the “Crumbles” where I would need to head inland and then circumnavigate. When I say wasteland, what I actually mean is an area of rough terrain predominated by shingle. No doubt in my mind an area of outstanding wildlife importance which would include almost extinct coastal flora, insects and reptiles clinging on at the margins.

Mais Non!!!! Zut alors!!! What was this? Like a scene from a sci-fi film set on another world, where no atmosphere exists, but humankind has raised its flag, rising high and as far as the eye could see, vast, apparently empty, blocks of flats. Marine, or more precisely, dock-land architecture set around a new yachting basin, and then marching on, Great Wall like, along the seafront for maybe half a mile before it abruptly ended. Any rare species that might have been lurking here at the time my map was produced would be long gone now. As much as I could understand the desire to own a sea-facing flat, built around a marina, this felt unsympathetic and brutal. Along the lines of, “we built this because we could.” I don’t know if it has been a success. Probably, but there were few boats at the moorings, and the vast harbour was about as lifeless as the Aral Sea (do check out what happened to the Aral Sea when you get a minute – in my lifetime it has vanished). A sole Martello tower stood out above the beach as a reminder that old military architecture can have more soul than some of the things we manage these days.

Maybe I was just out of season, and all the boaty people had retreated to the hinterlands or the Caribbean. If it was a British attempt at Dubai-dans la-Mare it failed to convey any desert allure, and I assumed that in the depths of November any remaining signs of life would be extinguished. Guess I’ll be checking ‘em out.

At the far east of the development everything just petered out and a track leading to the Pevensey Bay Sailing club ended at a large gate. I turned back and headed north on a road that flanked a golf course, where my old map showed nothing but shingle, and then inevitably joining the A259. Thankfully this only lasted a short while and turning to the right I zigzagged through the half decent new estates of Pevensey Bay, the most modern part set around another Martello tower, which only a few years earlier would have stood on its own in the gravel wilderness.

Into Pevensey Bay and down to the front and a pub with a garden and view out to sea. It was far too early to stop. Back on the coast road and through the older residential area of town, with its low eccentric houses and sea front homes that clung to the edge of the beach called Beachland (a perfect description). The road continued into the caravan park at Norman’s Bay. Beyond the park the road continued for a couple of hundred yards and finished, it seemed from the map, at an isolated beach. Only the second point so far in the journey where a gap appeared between generations of development. The gap was about 50 yards. I decided to stop for a bit, and with a snack in hand strolled onto the pebble beach and sat on a groyne. The view back to Eastbourne and the cliffs beyond was exactly why you’d come to this stop. The people in the nearby houses had chosen well.

Norman’s Bay and Pevensey – To infinity and beyond

The sea lapped gently through the shingle and gazing absently out I noted some movement in the water. It was exactly what I had not expected to see anywhere on this coastline. The head of a seal, just out beyond the end of the groynes, popping up and then disappearing. No doubt. I stayed on for another 15 minutes, trying to anticipate where the seal, or perhaps the seals (it was hard to be sure), would re-emerge. I was staggered and in something of a trance. I knew that with more time I could have stayed here for hours – just observing. I wondered how many people knew about the seals. Not many I felt. I realised that further progress here was not going to happen. Even the friendly council man who turned up in a van to empty the litter bins wasn’t sure if the road continued so, as I went back through the caravan park, I resolved to come back soon, with more time and a long lens.

Out of the park and the road passed under Norman’s Bay station. A bonus train opportunity for the future perhaps and just a short walk from the beach. The road continued inland, over a small river and then turned back towards the sea, under the tracks again and straight on through to Cooden with another station, easy access to a beach and its well-proportioned hotel.

Bexhill is a well-known quantity and so on up the hill and some winding through the leafy residential streets before back down to the seafront and pulling up at the Delaware Pavilion – one of the best architectural structures on the south coast, if art-deco is your cup of tea? In truth, for me, art-deco is largely brutalist, and unless well maintained, quickly tatty. But that can’t be said here. Time was ticking so I didn’t check out which tribute bands, or still just about kicking punk groups, were coming up over the autumn season so continued along the front, resolving to have the first stop in Hastings.

“Oh, what did Del-a-ware boy?” Perry Como will not be performing here soon

The cycle track kept to the coast, with the railway on the left for the next few miles and then the land rising at Glyne Gap with a panoramic view down to St Leonards and Hastings. A brief stop to take it in and then down and peddling between the track and the rows of beach huts. At the outskirts of St Leonards there was a siding and a large, evocative Victorian engine shed. The main doors were half open and peering in from behind the mesh fencing, I could make out the front of an older train that had somehow survived the scrapyards and was now being been restored. An electric multiple unit, painted in British Rail green. The sort that I grew up with in the 60’s and 70’s on the lines serving south London’s suburbs. In a previous life (the late 60’s, early 70’s), standing on graffiti hammered footbridges, at the ends of platforms, or wandering curiously around engine yards in North London where it seemed none of the adults gave a toss, I had probably seen it before. In a little book published by Ian Allan, containing all the numbers that were located on the front (or the side if it was a locomotive) of every train operating in the land, I would have memorised the four (or was it five) black digits – opened the book at the right page for the type, and drawn a pencil line through the matching number. Over the three or four years that this hobby occupied me (keeping me out of trouble, but not always), there was hardly a train running on what was then the Southern Region that hadn’t escaped my attention, and so of course, as time went by, the project to capture every number became more and more elusive. I can’t say why trainspotting appealed to me. In part, I am sure, it was just about being out. Away from home and neighbourhood. Exploring beyond the horizon. An innate curiosity beyond a comfort zone. Another thing to do when the weather was fine (when it wasn’t, there were always all the Footie magazines to get excited about, forensically reordering the league tables after the weekend results and searching for any vital insights about the stars of the day – particularly if they wore navy blue and white, haled from White Hart Lane and very specifically were called Martin Chivers). These things, with variations, is what most boys of my age did. Post-war, missed out on the Summer of Love. Waiting for something different, something glam, fast and loud. Not a fanatic, but for me, trains and the associated travel, filled that gap. The empire, of course, had been built on just such male juvenile follies. Practicing for power, influence and a predictable life of routine and bureaucracy. The empire was mainly gone, and the new reference points were Vietnam, the Middle East, and the bombs and bullets of the last legacy on the streets of Belfast and Derry. No books to tick off the discoveries now, but something still pulls. History though repeats. Maybe I’ll see that old unit again somewhere unexpected.

Tearing myself from the wire (literally), I pushed on, through St Leonards, with its unfortunate (and I am pretty certain misplaced) reputation, and on towards Hastings pier.

I know Hastings. I wasn’t about to be surprised by anything. But then, after recovering from the shocking impact of the massive, (and dare I say fully aware of the offence this may cause), art for art-deco’s sake, ten storey apartment block (Marine Court), like a battered white ship washed up in front of an exquisite street of a classic Georgian terrace (how pissed were the residents of those houses at the time?), just at the point where St Leonards morphs into Hastings, things began to pick up. Pleasant seafront properties, hotels and guest houses, wide, bike friendly promenade and a sun-drenched beach that lacked the massive defensive shingle structures I associated with Brighton. And there was music too. Ahead, and wafting along the Prom from a cafe… well, more a shack, the sound of lilting bouzouki belting out of a large speaker. There was no hesitation in deciding to lunch here. With the fine cream coloured Georgian terraces of Warrior Square behind, and the almost motionless still of the sea to the south, with a sandwich and a coffee to boost the powers I was about as happy as I had been at any spot on the mission so far. There was only one small problem. When I looked at the time it was 2:30. In itself this didn’t seem to be an issue. I had all day of course, but something was nagging at my new found contentment. What had Google maps hinted at last night? It was something to do with distance. A quick check and the on-bike device told me that since leaving Eastbourne Station I had only managed 16 miles. Yer…perhaps it was time to get going. Too much time spent seal and train spotting. I upped and left the Goat Lodge.

The Good, the Bad, and the Art Deco coast

Staying on the front I passed the troubled pier, then the discreet coin drop leisure zone, past the fishing boats pulled up onto the beach, with all their colours, through the old town, all black weather boarded smoke houses and the East Hill Lift, and finally to the end of the road and a view east, where the evidence of humanity stops and the high sandstone cliffs slowly erode. It’s a topography not common on this part of the south coast. It’s unstable, but it says “explore me.” Someday I think I will.

To get beyond this natural barrier the only option was to go back and start the long, slow, slog up through the delights of the Old Town, initially on the A259, then turning right onto Harrold (original!) Road that tore hard on the calves, and then a further right into Barley Lane with its impressive houses that stood well back from the cliffs beyond. The road continued at a steep gradient up past some detached houses on the left and trees to the right, flanking grassland that dipped away towards the high cliffs. Then through a holiday home park before becoming more of a track, dry as a bone. The track continued with fields opening up on either side, and then a left and shortly after, meeting with the Fairlight Road. A mile or so on, with glimpses of the rolling hinterland between gaps in the ancient trees, and a road and sign directing to Hastings Country Park heading back down towards the sea. A diversion, but maybe there would be a route down to Fairlight requiring exploration.

The road descended quickly (worryingly from the point of view of having to return in the same direction) and ended at an extended car-park. At the end of the car-park the road continued towards a coastguard station, but a wide and helpful looking path diverged to the left and down towards the target at Fairlight Cove. It seemed to be a no-brainer, but on studying the extensive information board that stood on guard at the head of the path, a problem emerged. As I was absorbing the information, from further down the path came the sound of rural authority as a woman, walking some noisy dogs, hollered to her associates something to the effect that an anti-social cyclist was about to break some sort of bye-law and she was gearing up for a confrontation. Having already resolved to act responsibly and to return reluctantly up to the main road, the opportunity for unnecessary confrontation was avoided. It was a disappointment. The headlands here, where the sandstones, mudstones and clays twist and turn in and out of each other, were spectacular. A place to make a note and put in one’s pocket for another day when the bike stays in the shed.

Back on the road, and now some 400 feet above sea-level, more eye comforting views north, and east towards and the levels on Romney Marsh. Now speeding down Battery Hill and then a junction with Fairlight Cove to the right. A quick look at the map. To have kept to the spirit of the exercise I should have taken the turn and reached the front, but the map only showed one way in, and one way out (and that was the “in”). I wasn’t up for that and so carried on the pleasingly undulating and winding road towards Pett, bringing back some youthful memories of being in an old banger (the owner would have disagreed), which had the road holding ability of a car with jelly wheels running on black-ice, as it danced and pirouetted hazardously on a trip between Rye and Hastings. Well, you had to laugh! Hmmmm….it’s possible that the term “boy-racer” had, at that time, yet to enter the language. We lived.

On through Pett village, the most westerly community that transcends the topography between the higher ground and the levels, where the sea had once been. Coming out of the village and hitting the flat, straight road to Winchelsea and Rye, a moment of profound sadness. I had been sent a text some weeks before with a message of mourning and so a should have been prepared when there, directly in front, was the Smugglers, a painted brick pub with black tudoresque beams and a pitched roof. An old friend. A blackboard stood at the front under the battered sign, with its depiction of a sailor steering a ship with barrels of something illegal either side of him. I glanced to see what was the day’s special. Not that I was stopping. There was nothing special today. And in fact, there wasn’t going to be anything special in the future either. In chalk, bold and without emotion. “Pub Closed.” There’s no way back for these places once it happens. In somewhere like Pett, when the pub closes, the developers come in and that, as they say, is the end of that.

The road continued with the huge shingle beach to the south-east. I stopped about half a mile out of Pett and pushed the bike onto the beach. A couple of people with tents erected, were setting up their gear and getting ready for a night chancing their luck for some on-shore harvest. The weather had held and the sun still bathed the beach and the green land beyond. A charming place, but something of a concern when looking to the south-west and the headland back towards Fairlight. The sun, whilst still there, was hanging…..well shall we say, a bit lower than I had anticipated. Too much pratting about. It was nearly 4pm. It was October. I had probably only done half the mileage needed. When did it get dark? The angle of the sun was definitely a clue and I needed to press on.

Remounting, and with intent, I cycled on along the beach road, and in the process (if maps are your thing) transitioned from Landranger 199 (copyright 1992 – roads revised 1990) onto Landranger 189 (copyright 2016 – revised September 2012). I now felt so contemporary and up to date.

Winchelsea next, after the road had turned inland past a holiday park. Turning right at the fine old church and then heading back towards the sea with a wide, lush green that defines the coastal part of the town. No time to take in the views as I headed out of the village and then onto the cinder and smooth tarmacked tracks that cross the barren, but wildly beautiful shingle and scantily vegetated flat lands on the way to the mouth of the River Rother. If I have mentioned it before I apologise, but there is something about cycling on cinder tracks that is overwhelmingly satisfying. Smooth, with a gratifying swishing sound as the tyres break apart the micro specs covering the harder surface below. It is a psychological trick of the brain but the sensation makes you feel that you are covering the ground at twice the average speed, which of course you’re not. You can also cycle without fear. Hands off the bars and sitting up straight to suck in the surroundings, with the marsh pools in the stony dunes and Dungeness power station shimmering on the horizon in the haze. Oh….so far…away!

Oh God! Sincere apologies. An oversight of the first degree in not giving you a fuller account of the historic town of Winchelsea. Well, actually if you’re interested you can always look it up. Defoe was disgusted and outraged when he found himself here sometime in the 1720’s. Two hundred years before his grand tour passed through, the town had held immense importance as a relic of Norman trade with France. A large town that was lost to the effects of the sea and silting, sometime at the start of the 16th century. There is little or nothing of it left now, though it still appoints “Freemen” that “elect” a Mayor. A nod to a corrupt past when its status as a “rotten borough” elected TWO Members to Parliament by a handful of worthies in a town which by then had a population barely the equivalent of a hamlet. I may mention Defoe again but his tour of the lands of England, Scotland and Wales (not sure about Ireland) is well worth dipping in and out of. Someone with a progressive mind, he was nevertheless a man of his time and was at ease in the company of the well healed and landed gentry, extolling where he found it, the fruits of enterprise. But whenever he passed through a place that elected disproportionately generous numbers of Members, he became catatonic with rage. So, as I say, I a lot of that passed me by.

The end of the path, and I was on the western bank of the River Rother where it ditches into the sea. A good number of people were out walking and exercising dogs and children. I stopped momentarily before setting off towards Rye harbour. It’s a place I know well and have a painful memory that even now brings me out in a rash of embarrassment.

Some years ago I stayed for a couple of nights in a motel by the river in Rye. A brief 48-hour escape from the brain bending mania of work, life and everything, but in truth, mainly work. Saturday evening arrived and with a plethora of charming and ancient fire warmed pubs to choose from, what else was there to do? I must have discovered a few, because on the Sunday morning I wasn’t so sure the break had been such a good idea. But hey-ho there’s always the sun (and the sea) and so after a continental breakfast that steadied the ship I wrapped up (it happened to be winter and very cold) and set off on a walk down to the sea. It so happens that due to the effects of nature, the sea has made quite a significant retreat from the old town of Rye, and so it was at least half an hour before I reached the windswept chill of the beach (where I now stood with my bike). It was a sunny day, but with no protection whatsoever, and probably not enough outer layers for the conditions, I instantly froze.

Not sure if the walk had improved my general malaise, reluctantly I gave into nature and made the decision to return to the motel. As I started the long walk back, to my relief, on the bank of the river, a substantial World War Two pillbox. Always explore a pillbox if you get a chance. On this occasion as well as a step back in time, it represented both cover from the elements, and a chance to recharge before the cold slog back.

After about five minutes, rubbing and blowing into my hands, I felt slightly better equipped to set off. Stepping towards the entrance, and then up the three or four steps, the bleeding (and I mean bleeding), inevitable happened.

When I was a teenager, along with everyone else, my hair was full, long and beautiful (really – it was!). But the Status Quo didn’t last forever. In truth, and rather rapidly into my twenties and thirties, the erosion set in with such a vengeance that by my 40’s there was so little left I was never to bother a barber again. I have always been totally at ease with this course of events, although I occasionally ponder on the likely cause, which vacillates between wearing a crash helmet every day for a few years to the chemicals in the shampoo that I used at the time. I’m past carrying now, and so won’t be litigating.

It is only when you lose your hair that you come to realise that of all the functions it performs (and if you can think of any you get a bonus point), one of its most important is as a protective warning device. The slightest contact with an object sends a message to the part of the brain set up to take evasive action. I bet you never knew that, but it is true. Since losing the hair on the top of my head I have banged and grazed it far more often than before. I can’t claim to have kept precise numbers on this but I know from experience that this is true. And it was just as true on that abrasive day a decade or so ago, because rough concrete beats soft scalp every time. As I emerged from the entrance of the pillbox, scraped but not hurting, I thought I had got away with it. Sadly, at that moment the cold wind whipped over my head, I instantly understood the cruel reality. A feeling, perhaps a bit like a raw egg being broken above, took hold, and on patting the part of my scalp which was the source of this sensation, the quantity of blood leaking out was immediately evident.

Did I have any tissue to help staunch the flow? Of course not. Just my hands. Did I necessarily have to worry about it too much? It was still early and I hadn’t seen anyone else so far. I started to lurch back inland at just the moment when, in the distance, a steady flow of hearty walkers could be seen heading directly towards me. I could tell you how I felt at this moment. How embarrassed I was each time a couple approached, took a look at me as I walked unnaturally erect and with my head high and angled in such a way that I hoped any signs of the still oozing blood were hidden, and then passing me by just a few feet further away from their original line of travel and mumbling to each other how on earth it was possible for anyone to incur a top of the head injury in this featureless desert. But I won’t, other than I felt like Basil Fawlty in the episode where he bangs his head, and that all the people passing me were wondering what on earth such a headcase was doing out on his own at such a place, and in such weather. Pity maybe? In truth, I suspect that they noticed nothing at all, and felt even less.

And there was that concrete object of hate. Still there ten or so years on, and with a little bit of scar tissue forever etched into the low ceiling. A short distance beyond and there sat the familiar black tarred and red roofed fishing hut, distinctive in its glorious isolation.

Heading north and past Rye harbour, which isn’t as impressive as it sounds, and then onto the mile or so of road with scattered industry that frustratingly took me directly away from the objective. Sadly, there is no way to cross the Rother until Rye itself so there was no escaping this. The road then linked up inevitably with the busy A259, just beyond where it had passed over the Royal Military Canal. On the A259, and heading into town, on the right the motel where on that previous occasion I may have been better advised to stay in bed.

Having spent quite a bit of time in Rye over the decades, I had no intention to spend any more than was necessary on this occasion. The road passed over the River Tillingham which ditches a bit further down into the bigger Rother. I followed the road along the east bank, where boats moor up and rise and fall great heights twice a day with the tides. The road flows through the newer south part of the town which sits under the old town defences. Rye is one of those places that still feels like its past holds a presence in the now. After dark, at almost any time of year, the cobbled streets are deserted, and the only life found is in the ancient inns that can be found on the main streets, lanes and alleys. If ever there was a place where the sight of a drunken, peg legged old sea dog, falling out the door of a candle lit tavern wouldn’t seem at all out of place, it would be in Rye. Believe me, I’ve seen it.

At the end of the town the road started heading north-east and crossed the Rother. The tidal river continues about a mile further inland. Just past the bridge, and on the right, a gate and a path that headed across a large field. I had found this route a few months earlier whilst spending a few days camping near Lydd, and after a very satisfying ride that took in the lanes across the marshes to Appledore, which sits on the low sandstone cliffs that were abandoned by the sea some centuries ago. At the Town Hall, in nearby Tenterden, a map on the wall shows a representation of Kent in 1250, and the extent to which the landscape of the marshes has changed since then is clear to see, and genuinely astonishing (see map below). The idea that, not so many generations ago, medieval people taking the higher lands from Appledore to Rye would have seen to their immediate left the sea lapping, or crashing, into the rocks just 150 feet below makes no real sense.

Crossing the field on the path to Camber, I noted again the occasional lumps of metal, and what looked like clinker, sticking out of the grass and earth, which made me wonder what the path was following or built on. Some months later I picked up a great little leaflet on a Colonel Holman Stephens from the small museum at the Kent and East Sussex Railway at Tenterden. Stephens was a man who drove the construction of light railways and narrow-gauge railways in unlikely areas across England and Wales at the end of the 19th century and into the early 20th. And this included, I discovered in the leaflet, a small gauge tramway powered by equally small petrol driven locomotives that took tourist and golfers across this very field, and then on to the Golf Club and Camber Sands. Opened in 1895 and closed to passengers on the day after the start of WW2, it was finally torn up a mere 50 years after its construction in 1946. I can’t help thinking that if it was still around now, it would be the “must do” way to travel for a few hours sunbathing on the famous sands. Golfers need not apply.

The path eventually met up with the coast road to Camber, but crossing the road it (National Cycle route 2) continues, flanking the marshes until arriving at Camber, where it was back onto the road, and then on east to Jury’s Gap, where, due to military dangers areas ahead, the road diverts inland and towards Lydd.

The last remaining buildings before the barbed wire and high fencing of State prevent further progress (if I recall from my list of acronyms an ANOB), is a collection of old coastguard cottages, set apart from the rest of the world. Back when the children were still quite young, some friends had rented one of these cottages, then owned by an elderly lady who lived next door. Acting on an invite to join them for a day we drove out of north London early on a dreich Saturday morning, eventually found the A21, and headed south across the Weald, with only occasional rain showers for entertainment. Groans of misery from the charges and protestations about having better things to do with their time.

I couldn’t counter the angst but despite the forecast (this was very much before mobile phones were able to give minute by minute weather updates for every street), as we left the A21 at Flimwell, surging forward through the lush countryside and towards Rye, I mustered up, and with a prediction based on no evidence at all, announced that all would turn out for the good if we held some faith in the transitory power of nature and the sun would shine through. And….as we started the descent through Peasmarsh and towards Rye, it bloody well did! And….it stayed out, the whole wonderful day. The cottages backed onto a large expanse of tufty grass, where the kids played and lay about, and where, towards the end of what had been a glorious afternoon, we started up a kick about that lasted a while. Until, unfortunately, just the moment when I was about to execute a Hoddlesque cross to the notional centre forward, my left foot found its way unaccountably, and extremely awkwardly down into a mole hole. That was the end of the game, and it seemed too, any prospects of a late career as a professional footballer. The two and a half hour drive back to north London should not have been attempted, but that’s hindsight. At the time it was complete agony every time I needed to apply the clutch, and the kids may have picked up a few new words in the process.

The bike route continues north east to the left of the main road and has quality views across the marshes, with large pools reclaimed from old sand and gravel pits and where wildlife abounds. I was in a rush, and so on this occasion, and in need of speed, I kept to the asphalt road. Maybe a mistake, as by this time my arse was beginning to suffer, and also because the underlying surface of nearly all the roads in this part of the world is concrete, designed to take the weight of tanks and other military “stuff,” and every few yards there is a gap of about an inch where the tyres bounce and the backbone takes a juddering hit. A pain (literally and metaphorically) but at the time a necessary sacrifice if I was to stand any chance of reaching Folkestone before dusk.

It was around three miles to the outskirts of Lydd, and at around the point of the first mile, Sussex gave way to Kent. At the first junction I turned right, flanking the town to the south, where it ended at the large fields beyond, and then left, this time flanking the town to the west. If I had turned right, and south, at this point I would have gone another mile or so and reached the campsite that I had stayed a few days and nights at the end of June. Further down the road, which I knew became a dusty, then ragged, pebble track, the end spills out at the vast shingle beach which runs back towards Camber to the west, and on a bit further to the east and the vast hulk of the still partially operational Dungeness Power Station.

If I had kept to my increasingly tattered principles, I should have taken this option, and then dragged the bike across the monumental shingle reach, past the power station and to the road beyond. But (and I rationalised this on the grounds of both recent experience and pragmatism), having weaved the bike through all these lanes earlier in the year, I had by proxy, completed this section. If I had taken the option I would have told you about the vast lake in an old quarry, now given open to water sports and freshwater swimming adjacent to a go-kart track. Also I would have pointed out the spot, where after a couple of beers in the Dolphin Inn, I wandered back to the campsite as the sun finally set, and where, from the field, a family of badgers emerged just yards ahead, ignored me completely, and then crossed the road, one of the adults rolling a pup in the process. A jaw dropping experience, which was right up the “wildlife in action” charts. But this was beaten hands down the next morning when, sitting outside the tent, with the first brew of the day, some sort of stoaty thing came bounding across the grass and darted into the bramble thicket at the edge of the field.

Exhilarating as that wake-up tonic was, just a minute later, and, trumping the sighting one hundred times over, a rustle in the hedgerow, and emerging hesitantly from a small hole in the thicket, the same predator, a baby rabbit in its mouth and then darting off at a pacey lollop back across the field. A creature, that with determination and knowing experience, knew exactly where it was going to find its breakfast. I can’t remember now where I had mine that day but it was probably a greasy spoon somewhere safer on the Denge Marsh.

Back in the world of ongoing reality and increasing pain, I reached the small roundabout at the edge of town and then took the right turn towards Dungeness. Before we get to Dungeness, just take a quick look at the 13th Century map of the area and spot the land at this point if you can (see map – I know I’ve said this before but we’re gonna get there). Of course, you can’t. As surprised as you, it wasn’t until I saw this map that I discovered that Lydd, still a sizable community, had once been the principal town on an island; an active and thriving port, until the inevitable happened. Now, at least two miles or more from the sea in all directions, it still retains its medieval layout, with some exceptional buildings, old and new, running along the edges of a huge, triangular green, which was almost certainly common land in the distant past. I enjoyed the few days I had in June in Lydd, though just a word of warning, don’t go for the cheese burger in the George. Until that moment I hadn’t realised it was physically possible to microwave a burger. The most disappointing and inedible thing I have ever experienced. But the Tandoori was excellent and, in the Dolphin, an amusingly self-deprecating picture, that hopefully was well meaning but is clearly open to interpretation. I Trip Advised (a rare activity) both the George and the restaurant. Surprisingly, the same day someone else posted a comment on the George. It was almost as bad as mine.

The road across the Denge Marsh was flat and straight. A steady flow of commuter traffic reminded me of the time (at that time, not a historical moment), and by now the sun was almost a memory as it sank away to the west, casting mile long shadows on any low structures that peaked above ground level. Always the power station hovering on the horizon to the south, and the network of monumental pylons and cables tracking off to the north-west. Here, the landscape was stark, mainly gravel based and arid, where the land rose a few feet above the extensive pools, ponds and lakes that provide so much habitat to wildlife. Beyond the large expanses of fresh water, the gravel dominated as the road crossed the famous narrow-gauge railway before hitting the east shore of Romney Marsh. A mile to the south the power station and the old lighthouses could have been a short diversion, but I had been there and done it back in June.

Hours of entertainment to be had here….Dungeness Power Station a few months earlier

At the time I had spent a couple of hours wandering around the area and then waiting for 20 minutes for a chance to take a shot of one of the trains coming into Dungeness Station. It was hot, and a few minutes after the objective was accomplished, whilst enjoying a cup of tea outside the newish information centre, come café, at the station, a group of middle-aged people, wearing middle aged summer cloths, and associated girth, emerged. As they stopped to take in the wide array of pleasures that the railway had brought them to, a chirpy chap in blue shorts and white buttoned shirt, turned and addressed another man in the group in eager anticipation.

“So, Trev, what’s to see and where do we start?”

The other man (who may or may not have been called Trevor), who, it seemed certain, had been responsible for talking the group into the day trip, gazed around for some inspiration, stroked his chin for a second or two, and perhaps with some time distorted memory of another time when he had been here, announced that there was of course the beach.

“Righty Ho!” the questioner said. “Let’s get going.”

To my shame, I did chuckle. There is a beach. In fact, it’s enormous, but let’s be honest, if the group had any idea at that moment that they were about to spend an hour or two on something akin to Camber Sands, they were about to be sadly disappointed. I left before they were back, but I didn’t doubt they were not too far behind.

So, I had cracked the main part of the journey and looking north and east along the huge sweep of coastline towards Hythe and Folkestone, I knew it was only a short hop before a large mug of tea and then the train back to St Pancras. It had just turned 5:30.

Map referenced above, twice…the insert of course.

I stuck firmly to the road flanking the beach. The tide was out. Whether it was coming in or out, I barely cared. As the very British anarchy of the higgledy-piggledy bungalows, shacks and houses that lined the road here passed me by, I knew that despite the ease of the road, and power in my body, something about the state of my legs was beginning to nag away. Another 25 minutes passed before reaching Littlestone-on-Sea and New Romney, where so annoyingly (I had forgotten about this bit), the beach road, and any navigable path, abruptly stopped. There’s been no new marina development here to replicate the Crumbles, and in its turn, grant you a new beach route. Even the new map confirmed this. What it also confirmed, and you won’t find this on Google earth, was a feature on the horizon. The sea was well out. I had seen this feature before but hadn’t given it a second thought. So, whilst writing this up, I took a look on-line to find out what the “Phoenix Caisson” was/is.

Left horizon. The Phoenix Caisson, like a memory, fading in the gloom.

As previously noted, this entire section of coastline is littered with the evidence of our military past. Mainly the bits that never saw any action, hence their survival. And the Phoenix Caisson here is another. A surviving section of a Mulberry harbour, intended for the Normandy beaches back in June 1944, but, unable to float, never made it.

So back inland, over the tracks again and heading determinedly away from the objective, another mile before a junction, a right turn and once more onto the delights of the A259. I needed to pick up the pace here, not least to try and keep ahead of the steady flow of vehicles making for home. By now the sun had gone and the light was running out quickly. It was already another of those days where, on reflection, it had become impossible to relate the events of the morning to the present. The utterly differing landscapes creating a complete and confusing disconnect.

All I could do was plough on. And I did. Through St Mary’s Bay, back along the front for a bit, and then Dymchurch, with no time to take in the surroundings.

The last snap – somewhere before the night.

At Dymchurch the road veered through the town, and then back onto the coast, where I left the road, and for a mile or so, cycled freely along the concrete slip above the beach. Dusk by the Redoubt at the end of the strand, back onto the A259 and onwards through increasingly urban and light industrial areas before finally entering the larger town of Hythe. The road snaked around the western suburbs and then joining up with, and then following a short stretch of the Military Canal. With the daylight almost vanquished I was at peace. No lights for the bike but I knew it was just a matter of minutes before the final destination.

Hythe morphs unknowingly into Sandgate, and as I approached the invisible frontier, with substantial Edwardian houses on my left, everything suddenly fell apart. Not a full-on assault but the familiar early signs of cramp wrapping around my right calf muscle. The chances of a full on, and hideously painful event was, based on historical knowledge, about 90%. In order to mitigate I stopped and gingerly rubbed the back of my leg for a few minutes. This eased the unnerving sensation enough to start off again, but the danger of applying too much power was in the back of my mind, and so progress was snail like. And then, the left calf went. Over compensating, almost certainly, for the rights incapacity. The same process. Stop and repair. By now the darkness was in full on wrap around mode, and if at that moment someone in a truck had stopped and offered me a lift, I’d have snapped his or her hand off. It didn’t happen. Where’s the love gone people?

At a hopelessly slow pace I glided through the pleasant Georgian and Victorian dominated town of Sandgate. A nice place, with excellent beach walks and pubs, which I might have seen if it hadn’t been dark.

The one thing about Sandgate that is not so good, especially if you are on a bike and have just managed over 60 miles on a hot day, is the hill on the A259 leading up to Folkestone. I hadn’t forgotten about it, but I must have mentally downgraded it, because, half way up, and with a sensation across my thighs that I had never before experienced (something like I guess you’d feel through medieval torture where the skin is stretched so tight that it burns, and just before blood oozes out of every pore), and with a bus thundering up the hill behind me, determined it seemed to take me out, I gave up and pulled over. I think I may have wanted to cry at this moment. I was there, but I wasn’t, and didn’t have any resources left to respond. Almost defeated, I pushed on up the hill on the pavement. The gradient was, for a short while, severe, and my legs were almost about to lay down their arms. Confusingly, I was at no stage out of breath or exhausted. The rest of my body was in tip top form, but the burning sensation in my legs was in open dispute.

The rest is not worth mentioning. When the hill flattened out, I remounted and slowly peddled on through the big residential streets to the west of the town centre, and then north to the outskirts near the motorway. Every turn of the peddle was like another nail, but I was there.

The log-legged, long slog into the darkness.

Niceties out of the way I collapsed, absolutely, on to the nearest sofa and apologised profusely for the late hour. I had taken a lot from the day, and the day had taken even more from me, but I had discovered some things, and with the exception of one or two other occasions, felt as healthy as I’d ever been. Half an hour later, and not a smidgen of life had come back into the tree trucks that extended uselessly forward. The idea of getting back on the bike, and the one mile needed to get to Folkestone East station, was so beyond impossible that it never even entered my head. That was that and it wasn’t until the next morning that I stood at the platform waiting for the Javelin back to the Smoke.

And it wasn’t until drawing out the coastline for the maps above that it became apparent that when I had looked down the bay from Dungeness to Folkestone, happy that I was just a short hop away from base, in fact, there was still over a third of the journey left. What a mug!