Closing the chain – the final link

Landrangers 178 and 179

53 Miles

The hot, memorable, record-breaking summer was slowly ebbing into autumn. Was it as good as 1976? Debate. An exceptional one certainly, but in ‘76 I remember two weeks on a campsite in Denmark with a mate where not a cloud stained the blue. As the sun rose and tasered in through the thin canvas it was up and out at 6 am every morning, regardless of the hangover.

On a day back then, when the sun burnt through to the earth’s core, we ventured out from the campsite on two hired bikes and headed west. Two hours later we arrived, exhausted, at the coast. Huge sand dunes, over which the bikes were pushed, pulled, and thrown down in something close to hatred, defended the sandy beach where the concrete evidence of past conflict abounded. Immediately stripping down to pants, and then flinging ourselves into the North Sea, it was only three seconds before the shockingly cold water, supplemented by icy currents from the Arctic, had us back on dry land where, through refreshed eyes, we quickly realised that we were the only people still wearing any clothes. Despite considering ourselves open minded, out of sight, and largely in a groove, the truth was that our coy suburban English upbringings held us back from joining in the fun. Whilst we may have missed the summers of love, undaunted, we’d retained our pants.

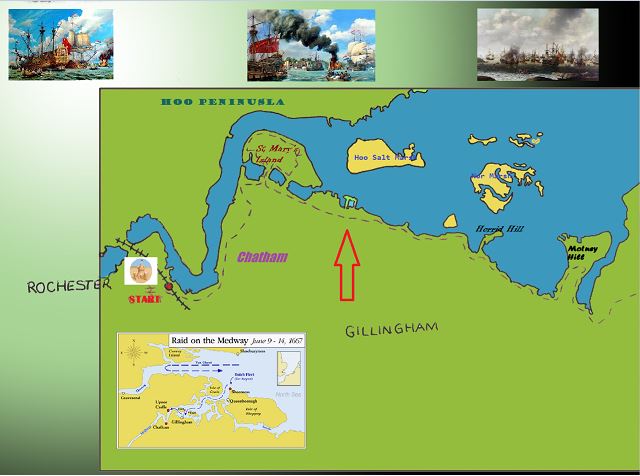

Forty-two years on and the days were definitely getting shorter. Four weeks after the “north Kent debacle” (as it will now always be known), the scab on the left shin still clung on. A symptom of age – I guess? And I’m back at Rochester. One last piece in the coastal puzzle (the missing link) to complete, if you exempt Sheppey on the grounds that it is indeed an island (despite the bridges), and the little bit of West Sussex between Littlehampton and wherever which will need to wait for another year.

It was a cold morning and I wasn’t feeling particularly well, but the reality was that the windows of opportunity were slipping away by the day. Not in any way similar to say an Apollo moon launch, or an attempt at a particularly difficult mountain summit, but as I have said before, in every way I am nothing if not a fair-weather cyclist. I don’t do hardcore, self-inflicted weather pain.

Despite the sense that the whole project was not a million miles from being an exercise in flogging a very dead horse there was still an ounce of motivation in the system, and at some time around 9:30 I was back at Victoria station with the e-ticket I had procured on the internet the previous evening. Boarding the near empty train, I found a seat, this time nowhere near a toilet. The train left and then arced through south London on a section of track I had no recollection of ever taking before. At Bromley South I had to change trains. The transfer time between the two trains was just a few minutes so, when the train had stopped some miles short of Bromley, and then failed to progress further for what felt like an aeon, I knew that if I managed to make it to Bromley in time, it would, to use that new Brexit term that none of us had heard of until three years ago, be a “just in time” dash to the Rochester connection.

And so it proved. Running down the platform and lugging the beast up the stairs and then down again, with just seconds to jump on the connecting train.

At Rochester station I started to head east, crossing the A2 and then along the old High Street which seemed to be in Chatham, or alternatively, could still have been in Rochester. Daniel Defoe had very little to say on Rochester. “There’s little remarkable in Rochester, except the ruins of a very old castle, and an ancient but not extraordinary cathedral…” I don’t know if the remains of the cathedral are still there, but despite the size and reputation of the ruined castle, somehow it too is not extraordinary and barely registered. Unlike other medieval offerings of the same type and era (Conwy and Dunnottar come to mind), it seems diminished by the clutter of centuries of random development which has grown up and surrounded it. I’m certain it pulls in sufficient numbers to justify its continued existence as a ruined timepiece, but a bit of me thinks that a Battersea power station type renovation and upgrade might not go amiss. Just putting it out there?

Meeting the River Medway at a newish housing estate, I was then shunted back onto the High Street and eventually back onto the river bank at a small park area with a jetty. There a man was dispensing about two hundred weight of white bread to sea birds and pigeons that must have thought all their Christmases had arrived in several huge plastic bags. The hideous sight nearly had me retching, which certainly is what the birds would be doing later after they’d had their fill.

Of course it was far too early to enjoy a drink, but just a little further on and I stopped for a few minutes outside an imposing and beautifully constructed Georgian pub called the Command House. The building fronted west across the river and I wondered what historic moments would have occurred within its snugs over the centuries; and more recently on lager fuelled Saturday nights. A superb spot to enjoy the sunset over a late pint, gin, porter or rum, before flicking your used clay pipe into the river at closing time. Disappointingly, having researched this further, although first documented in 1719 (nearly happy 300th birthday), it was a store house for the Admiralty, and only became a public house in 1978 (happy fortieth)! It appears to have had a lively licensing existence since then, which could account for the missing D. Not everything is what it seems!

A river path continued for a short while, and then diverted back to the main road which wound up-hill towards one of the entrances to the historic dockyards, with its high brick walls. Shortly afterwards I was crossing a bridge over some water between two basins. I was now on St Mary’s Island, and tracking through modern low-rise housing where construction was on-going and which Google Earth doesn’t seem to have caught up with yet. At the time I hadn’t appreciated that this really was an island, bridged at several points to connect it with Chatham’s historic dock yards, but by being there I had breached a fundamental rule of the mission. As small an area of land as it was, it wasn’t the mainland, and the whole evil spectre of Sheppey (my personal Banquo) reared its head again, not least because at some point soon I would be looking at it directly across The Swale.

Cycling between the new-build, where I got a bit disorientated, I was kindly redirected (I gathered on the grounds of health and safety, and for not wearing a hard hat) by a builder with the broadest Geordie accent south of the Angel of the North. I reached a path by the river facing west, and towards Upnor which I had travelled through just a few weeks earlier. A nice spot, with a decent view and new homes that looked liveable in. The wide new path headed north, but first there was an important information board that had to be read and digested. Lots of the information that I read I completely failed to digest, and so took a photo instead.

The gist of it was that St Mary’s Island is a very historic place. Once a hellish marsh only fit for mosquito’s, and burying French soldiers captured in the Napoleonic wars and who had died (almost certainly mercifully) on one of the old hulk prison ships laid up nearby. Maybe a memorial to those poor desperate souls wouldn’t go amiss, but what country honours the defeated?

No small irony then that the reclamation of the marshes, and their incorporation into the huge Chatham dockyard network, was, oh err…..done by prisoners! Our own this time. It was such a jolly old era in the days of forced labour that inevitably perhaps there was a convict’s riot. I don’t know what the score was in the end because I’ve forgotten, but I’m guessing the Admiralty won. It usually did.

Now you’d think, wouldn’t you, that this was more than enough history for a few acres of inhospitable marshland. But fear not, there’s a lot more to it than that, and perhaps the most interesting historical detail reminds us of the important truth that if you fail to invest in the infrastructure of State, the best laid plans can still, and often do, go pear shaped. In this case the plan was very actually laid across the river, from St Mary’s Island to Upnor Castle on the Hoo peninsular opposite.

An enormous metal chain was attached to a winch at the Castle, then lain across the river bed and anchored to the St Mary’s side sometime in the 16th century. The idea, brilliant when you think about it, was that if any Johnny foreigner types thought they’d try and sail their men ‘o war up the channel, they’d come a cropper on the chain, which could be raised above the waterline in times of danger. Just in case, there were also a shit loud of forts and castles built on either bank and any acre of land above sea level in the estuary, with hundreds of guns trained on the channel all the way from Upnor and then north to Sheerness and beyond.

And so, in 1667, when a Dutch fleet, sent to cause a bit of mayhem in the estuary following some sort of endless war with the Crown that the Dutch were getting very pissed about, actions stations were sounded….but…..Ahh! Due largely to austerity measures caused by both the war and the great fire of London, no-one was around to respond! Not only was there no-one around (which meant that the handful of remaining guns lay silent and the ships stayed in their docks), the resultant panic led to decisions being taken that in hindsight were probably at the least rash, and at best, hopelessly inadequate. After shooting up a few things in the estuary over the first couple of days, and taking the fort at Sheerness (which was manned by the cook, the rat-catcher and the candlestick maker), the Dutch did the thing that no-one thought possible. They sailed into the Medway, made their way to the main docks, sank a loud of ships of the line, and incredibly made off with the flagship of the fleet, the HMS Royal George. In the build-up to the attack, and in a complete panic, the local naval top guy, perhaps understandably, scuttled a load of the older and less useful ships in the channel with the aim of preventing the Dutch making further progress. Good idea? Except he wasn’t able to sink enough of them in time and the Dutch, with a Johan Cruyff like shimmy round the sunken defences, glided by and on towards the main goal. But of course, there was still hope. Wasn’t there? The old Gillingham Chain, ready to rise from the depths like an old leviathan. Hmmm….so not sure what 100 years of rust and disrepair does to iron, but it’s safe to say it failed to bother the flying Dutchmen one iota as they managed to pull off the raid to maximum effect. Not too long after, the British agreed a peace with the Dutch, which I’m guessing was probably for the best. There was no sign of the chain now.

For the Brits this must have been like an earlier version of Pearl Harbour. Unlike the Americans, who very quickly went into full fast forward mode and within weeks was giving it all back at the Battle of Midway and then beyond, we took this setback on the chin and made peace. There were to be no further skirmishes on the polders or the marshes. As far as I know, until the emergence of football violence in the 1970’s, neither the Dutch, or anyone else, came to fight a third Battle of the Medway. Unlike Rochester, Defoe pours lashings of love on Chatham, which, by the time he arrived, was once again the powerhouse of Britain’s naval power and industry. He too reflected on the Dutch adventure, describing it as a “dull story in itself.” Given that it sounds anything but a “dull” story, I assume he meant in a “sobering” sort of way, rather than a Dutch version, where, no doubt, there still is an annual national day of celebration on or around the 6th June. Although we have one too on that date it’s for something else completely.

As much as the history of St Mary’s was fodder for more thought (did I mention the Romans and the first Battle of the Medway?), Herne Bay seemed a million miles away, and onward progress got me back on the wheels and the path that arched round the bend in the river.

There was nothing not to like about this place, unless your French or criminal ancestors were buried here. Oh…unless some key requirements include a pub and a tandoori, of which neither were in evidence. At the northern point I could make out the place on the Saxon Shore on the Hoo peninsular opposite where, some weeks earlier, I had abandoned the coastline due to a high tide, and had headed inland to achieve Rochester before dark. A bit further on and I stopped again. Just down the bank was a boat, shimmering at its lashings and not of our era. A small paddle steamer of some sort, no doubt in the long, slow process of restoration (or advanced corrosion), and in the watery light a memory of oil paints and Turner.

In his famous painting, The Fighting Temeraire, Turner paints a scene in which a modern steam powered paddle tug boat pulls the old and distinguished ship of the line up the Thames from Sheerness to Rotherhithe to be broken up. It is thought to represent naval decline. A recurring theme it would seem, but probably a bit wide of the mark given its continued world dominance over the following 100 years. Well, he wasn’t to know. As I stood at the sea wall and gazed at the pile of rust moored just along the shore Sheerness was in view to the north. So, nearly 200 years ago, you could have stood at this point (as a prisoner of one sort or other) and maybe seen the Temeraire being pulled out of Sheerness by something not unlike the small vessel now before me. What you wouldn’t have seen was the sun setting in the east as Turner represents the moment, because of course, that’s impossible.

I wove back through the newly formed streets on the Island, through a small landscaped park, crossed back over the basins, got a bit lost for a minute or so, and then onto the busy Pier Road, set back from the water by a few hundred yards and with new housing developments rising out of the old industrial zones. At some point Chatham became Gillingham. It wasn’t clear where this was, but taking a turn to the left and I was then in a riverside park with a lido and The Strand, which ran along the bank and off to the east. A number of concrete barges (don’t worry I won’t be recycling that dreadful joke from before) lay like recumbent seals on the mud.

Some zig-zagging and then eventually I was on a path with fields and parkland to the right, and an expanding view of the Medway estuary to the north. Then a large bay, with the wrecks of a number of small boats and an isthmus that led to a body of land, hovering above the waterline, called Horrid Hill. I cycled along the man-made road that led to the “hill” but stopped before venturing into the trees. For completeness I should have continued. It wasn’t far but something held me back and I carried on through the Riverside Country park that seemed to be a great asset for the area. I have no idea why it was called “horrid” but maybe it was the unknown that held me back.

A mile or so on, and another bay. The concrete remains of what appeared to be some sort of dock, that would have served some sort of industry at some point in time, was a suitable point to stop for a minute and gaze out at more boats and barges that had ended their days in the creek, where now they were slowly being consumed by barnacles, salt and silt.

I followed the coast road at a point called Motney Hill (no, sorry, don’t know the origin of this one either), where large flocks of wading birds filled the air above the water, and where more dazzlingly white Little Egrets than I had ever seen before in one place, stalked the foreshore spying out their lunch. Up the hill and the road ran out at the entrance to a water treatment works (aka sewage farm). At this point I could see that I had arrived on another, much larger isthmus and with a creek to the east. I could have just gone back down the road. But, temptingly, there was a metal gate type stile, trying hard to hide from the masses and set into an overgrown hedge. Without further thought I was mashing the bike through the complicated and clearly unused access point, before carefully peddling along the rutted path with nettles threatening, and where, inevitably, one or two of the critters planted their barbs on my exposed flesh.

Coming out of the short, albeit annoying nettle zone, the path led into a field and then along the side of Otterham Creek, with an excellent expanse of water and fine countryside beyond. This won’t mean anything to anyone other than a very small minority, but for the whole time I cycled along this section, and for a good part of the day thereafter, I hummed the Fall’s Cruisers Creek. At that moment it seemed so appropriate.

The path eventually looped around the back of some warehouses and then to the entrance of a boatyard with a row of council type semi’s that were in the process of being renovated; I think for private sale. The path then met up with a road which continued north east. There might have been a coastal path here but I didn’t seek it out, content to be back on asphalt and making progress again.

Up past fields on either side and soon I was at the village of Upchurch. As I passed the said church (St Mary’s the Virgin), a quick glance to the left and I noticed a small green sign indicating Commonwealth War Graves. With the sun high, and a good few miles under the belt, it seemed to be a good time to stop and have a short wander. An attractive flint building with a four-sided spire which seemed to have been concussed by the implantation above of a wooden spire structure with eight sides. The graveyard led past the entrance and then on down the slope of a hill, where more recent burials had extended the land. The handful of war graves, in various spots, were easy to pick out by their common design and well-maintained white marble plots.

There was a Private H Thurley of the East Kent Regiment (The Buffs), killed on the 1st February 1917. Stoker (1st Class) William David Baker died on the 20th October 1918 whilst serving on the HMS Valentine, a new destroyer that went on to play a part in the Second war but which took too much incoming from some Germans Stukas off the Dutch coast and lies there still. Stoker Baker seems to have been unlucky. Just 22 days short of the end. Corporal A V Stapleton of the Royal Engineers was just 9 days short of the Armistice; 2nd November 1918. There seemed to be an emerging pattern. The only other grave to be found was Stoker 2nd Class S W A Mercer, who was serving on the HMS Dominion on 28th November 1918; just 17 days after the peace. By that time the HMS Dominion was an accommodation ship berthed at Chatham. Who knows how Stuart William Arthur Mercer died, but he was 28. Possibly of his wounds? He was born at Rainham, but by 1901 was living in Upchurch and married at this church in 1914, just four months after the war started. You can find this on-line, along with a comprehensive family tree going back to the late 18th Century. There were a lot of Fishers and Mercers in the family line, agricultural labourers mainly, but also a couple of policemen (M) and a school teacher (F). Someone had gone to some lengths to put this together, and as a portrait of what a mainly rural life must have been like leading up to the 1st World War, it makes for an interesting read.

I have seen similar census details for a small fishing village on the Scottish coast south of Aberdeen where once there were family links. A small number of extended families housed in small, peat roofed cottages, running down a dusty street that ended at the cliffs above the bay, where below a breakwater provided safety for the boat, or boats, that allowed an existence. The difference was, that whereas everyone to a man and women in Stoker Mercer’s family was born, bred and died in Kent, every so often in the Scottish village, perhaps because the nearby sea opened to a wider world, an interloper is recorded. One or two from other parts of Scotland, someone from the north-east of England, and someone from Ireland. A modicum of diversity that in other similar communities could have included people from across the sea and Scandinavia.

Stoker Mercer survived the war, but wasn’t able to enjoy more than a few days of the peace. It was the most poignant. I once knew someone who shared a similar fate in a place 8000 miles from here many years ago.

I cycled on and out of the village heading north. The map showed that a road looped round what was quite a significant peninsular. The lane was surrounded by fields and for the first time I noticed orchards. A butterfly (a Peacock I think) skipped out of a hedge and fluttered by. I don’t know when butterflies stop fluttering around in the UK, but given the time of year it felt like a very late outing, and I assumed reflective of the extraordinary summer.

This was an area that felt like it hadn’t changed very much over the centuries. A scattering of road side housing which all seemed to have had agricultural heritage. I shot past one on the right. A distinctive light-yellow painted house which looked at least 200 years old. Maybe it was the colour or the style that must have held my attention for a brief moment, but was enough to allowed me to spot a round blue plaque mounted above a ground-floor window. Curious, and in truth staggered that there might have been someone of note living in this house at some point in history, I circled back to get a closer look. In my mind I suspected a novelist, or maybe some old sea Captain or other old cove who plied his business out of Chatham or Sheerness. So, and once I had managed to focus the deteriorating lenses accordingly, I was astonished to see that at some point in time, the characteristic frame of James Robertson Justice would have once graced the doorsteps and environs of this modest pile.

For those of you too young to know, said JRJ, was a character actor who appeared in numerous films in the 40’s, 50’s and 60’s. I say “character” actor, but the truth was that he only every played one character – himself! That is to say, a large bearded man who played a larger than life post war bore. Okay, I’ve said it, and I know that will upset some, but basically he was in the films what he was in life (except a doctor from memory). To be fair, some of those films do stand the test of time, and his character was apt for the parts. Examples include perhaps, Storm Over the Nile, in which he plays a crushingly gregarious old soldier of Empire who just can’t stop hammering on over Port and roast beef, about the number of foreigner’s he’d put into the ground. Or as the narrator (he did quite a lot of that), and the part of Commodore Jensen, in the literally iconic and uber star studded, Guns of Navarone (I can’t believe that I have managed to slip this reference into an account of a cycle round the Kent coast so big thanks big man).

Of course (keep up children), he is probably best known for his role as a doctor in the “Dr in the House, Dr in Distress…” (the list goes painfully on) series of films in which he starred with many other great luminaries of the British innuendo and carry on scene. Don’t get me wrong. I was brought up on this stuff, and whilst I can’t see any reason at all why I would ever watch any of them again, I’m not knocking them. That said I think I always did have some sort of aversion to the JRJ doctor type character that he played in these and other films where a truculent, arrogant, self-opinionated bullying brute was required.

I was born with a small deformity (turns to camera and whispers “..look, shush, there’s no innuendo happening here!”). The second toe on my left foot to be precise. It’s a monster! Twice as big as it should be and probably either the result of too much strontium 90 in the air (my mum’s theory), a certain pill that was being prescribed to pregnant women at that time (my mum’s other theory) or just a genetic accident. In the womb I had six toes on the left foot, and at some point, two merged together to produce one mega-toe, that in life would go on to be a right royal pain in the left shoe. And not enhanced, I have to say, by the early 70’s fashion for black leather, pointed toe, three-inch stack heeled zip up boots in which I staggered in agony to and from school each day, and to the occasional Sunday night gigs in town. As the fashions changed, presumably for the better, I became less aware of what I can only say was a very minor disability.

But, sometime into my early thirties, and for no reason I can recall, the toe began to re-assert its authority on my pain threshold, and after months of putting it off, I sought some advice from my GP. I probably just needed the attention. The GP (male or female, I can’t recall), scratched his or her head and understandably, just to get me out of the consultation room, wrote out a referral to the University College Hospital (UCH). With the ticket in hand, and a few days later, I entered this great medical institution (which had also, rather noisily, brought my daughter into this world), and waited on a bed for the person who would come and offer me hope. What I thought the options on offer would be is anyone’s guess. So, when a large, bearded man in a white coat, and oozing imperial authority, strode towards my position, rattled my toe for a few seconds and then announced in a booming, superior Edinburgh voice that there was nothing to be done other than lopping the critter off, I knew I had just been JRJ’ed. As his honour turned to seek more important victims to inflict his wit, justice and scalpel on, he turned back to me, tweaked the end of his beard, and added in a tone not to be ignored, “Off courses, there is always “Makepeace” of Bond Street. Handmade mind! Always found ’em very accommodating. Be able to knock you up an odd size pair or two I’m sure. Take my word for it old man.”

My monthly contributions to the NHS were, in the end, not to bring me relief. The prospect of decapitating my lifelong appendage did not appeal. Neither did the thought of a life scrimping away in order to procure odd sized shoes from a well-established firm in Bond street. So, I just put up, shut up and laced up.

How and why JRJ ended up on Poot Lane, in the middle of nowhere, is anyone’s guess. I can’t find any references, but judging by on-line biographies, he may have been the sort of chap who needed to keep on his feet; moving on from town to town as he romanced his way through the women of whichever parish he had landed. But there you go. At some point he ended up here. Maybe to escape? I took a photo which I won’t share. It’s a lovely house, but given that it’s in the middle of nowhere I’m guessing the current owners value their privacy and aren’t particularly keen on having busloads of 60 plusers gawping through their front windows. And, just in case you thought you could cheat and look the place up on Google maps, forget it. I’ve just spent two hours (not in one go) trying and failing. Nearly losing my mind in the thought that I may have made it all up, it was only after a lot of double checking that I at last found it. And, the reason why you won’t find it (I don’t know who I think I’m addressing this to because no one is going to be reading this) is simple. The picture on Google is some years old. Along with some other details, the paint job is now different. So, when that small smart car with the camera on the roof passed by (whenever it was), the blue plaque club had yet to get around to erecting the memorial. So there!

As much as I would love to continue this nostalgia diversion – let’s not! The day was no longer young. I continued doing the rounds on Poot Lane, through the communities of Wetham and Ham Green’s, and only seeing two other people; one a man on a tractor going between fields who looked like he wasn’t from around these parts, and one, an older man at the end of a lane who was pottering in his garden and gave me a look as if to say “turn back sonny, I’m just a speed dial away from calling Neighbourhood Watch.” And then I was off the peninsular and onto Twinney Lane. A brief diversion down Susan’s Lane that led to the next creek and then back again after finding the route blocked by the local dust cart. The next community, Lower Halstow, was small, but comparatively on a vastly bigger scale than either Wetham or Ham’s Green, and the streets through the residential fringe took me down to another small creek where a well restored Thames barge lay at the mouth of the small river that drained the land around.

To the north of the village, a country park had emerged out of an old brick works and I noticed that I must have missed some coastal path alternative at some point, because it emerged here from the park. Was I upset? Not really. This had evidently once been a very small community, which from perhaps the 1950’s onwards, had expanded considerably. There seemed to be three distinct growth phases. Next to, and around the much earlier handful of scattered houses and an old pub that would have housed and refreshed farm workers and brick makers, a string of corporation type, and private semi’s, from around the 50’s, 60’s and 70’s. To the south of the pub, another area of newer buildings that could have been from the 80’s or 90’s. Finally, to the north-west, and perhaps in part on the site of the old brick-fields, a far more recent quarter. As a village that might be well placed to tell the story of rural development in the country over the last 100 years, I sensed that Lower Halstow could probably do a good job.

Over the river, and then past the attractive church (which lacked a second spire), the lane passed out and beyond the village to a wider road that headed back in land. Another low peninsular stretched to the north. Almost certainly I was missing out on more coastal walk action, but I really had had my fill. The view between the hedges provided the occasional glimpse of the water that lay between the mainland and the Isle of Sheppey. Then along the shore of a bay before crossing more land and low hills that eventually provided a much better view east and towards the road and train bridges that crossed the Swale (the expanse of water dividing the island from the land. The land here was flat; reclaimed and although still full of late summer green, desolate. At the bridges a path did lead to the riverbank. A police 4×4 sat idle at the end of the path. Presumably a late lunch before another shift on the Kent highways.

Under the bridges on the track, and on along the marsh wall. Well, I was on it now (the Saxon Shore Way), and had resolved to get back to basic principles whether it killed me or not. The map indicated that the path continued through to Sittingbourne. But after about half a mile of rutted and awkward cycling, the path didn’t continue to Sittingbourne, and instead came to an abrupt end at an industrial complex. The facility may or may not have been there when the map was drawn, but one way or the other, in the spirit of expansion, it had severed the link. I wearily rode back a bit and saw a path running along the side of the works. Flanking the high fence, on an even less even track, and soon I was on the dusty road that serviced the facility, and heading back to the west. Shucks! This was no fun. And it became even less so when I realised that I’d been snared into a dead-end trap, eventually emerging from it by going back under the bridges, and then heading south-west on a straight road that soon arrived at the large village (or small town, take your pick) of Iwade. A town (or large village) that I had never ever heard of before, but which, like Lower Halstow, seemed to have expanded at an exponential rate in a very small number of years. In fact the reason I may never have heard of it is almost certainly because, with the exception of a small number of Victorian buildings in the centre, which included an old pub, the “town” of Iwade almost certainly didn’t exist until the last ten years or so. At least three times the size of Lower Halstow, this was a new community, risen from the marshes, and putting its footprint very much on the Earth. Not too bad either, though naturally the name had left an indelible imprint on my mind, which, when cycling, can loop ideas over and over again as the peddles and wheels turn monotonously on, banishing any deeper considerations of the meaning of life and all that. And so, as I progressed on, the Fall’s Cruisers Creek was replaced immediately by Under the Moon Above. If you’re struggling with this concept and the connection I do understand, but think Leicester 70’s, throwback rock and roll band, and you too could be just Three Steps from Heaven.

Cycling resolutely south through the new community, and then a left on a minor road that led downhill to a complex junction that crossed over the A249 main road to Sheppey. Beyond the A249 and along Swale Way with industry to the north and more evidence of residential development to the south. A good mile or so on, and through a series of small roundabouts then across a tributary of the Swale, through more industry and finally, this obviously new road, petered out as it led into another new housing scheme on the eastern edge of Sittingbourne. A new community that was still in that limbo state where many of the houses were completed and being lived in, whilst large muddy plots were still being dug out and where many more new homes would rise up over the coming months.

Back in 1970 I was transported, as a 12-year-old, onto a new estate that was in a similar state of development. In truth, and I am not sure I have ever quite got over it, I felt as if I had been wrenched from a place of stability and relative contentment, and dumped, without any thought for my mental well-being, into an alien environment where I then spent years trying to adjust to an awkward and new reality. You’ll be pleased to know that despite an urge to burden you further with the teenage woes that were inflicted by this trauma, I’m over it! Really, I am! Honestly.

I was now definitely a bit lost. None of these buildings were on my OS map and all I could do was guess at whether or not each next turn would, like a maze, lead me onto the next curved street, or loop me back into a cul-de-sac.

After being lured into one of these cul-de-sacs, and running out of hope, I found a young couple outside their house and sought directions. They were happy to oblige and within 2-3 minutes I had been given all the information I needed to complete the puzzle and reach the next level, which meant escape from Sittingbourne, or whatever this area now was. I was very grateful. Setting off I gave a thumbs up, and only a turn or two later, was completely and utterly lost – again!

Fortunately (not), and returning to the theme of my own displaced youth, I fell upon a group of boys, possibly aged between 10 and 14 who, on bikes, and many with hoods up to protect them from the searing sun, and in something of a pack, were circling posse-like at the end of the road I was now heading up. I recalled those wonderful early 1970’s days when, after spending a few weeks with the local skinheads in an effort to fit in, I moved on quickly, and became a fringe member of the local puppy greaser push-bike gang, which, I’ll be honest, was a bit of a damp squib when it came to matching up to the other local, and more energetic, friendship groups. We were simply no match for their untamed violence.

But, here and now, and having just watched a wildlife documentary on a pack of African Wild Dogs, and also having spent too many years professionally observing the cycle of life on inner London estates, I instantly recognised some of the key behavioural traits of this aspiring group of highway robbers. How that manifested itself was that in the space of a slit second, and as if through some sort of kinetically transmitted connection, they all clocked my weary progress, and with all heads turned in my direction, changed the direction of their bikes, and began in unison, to wheel in mesmeric formation towards me. I think I pretty much knew where this was heading. I certainly didn’t think that violence was going to form part of the estate introductory package, but some sort of humiliation was no doubt on the cards. And so, like the old, lame and vulnerable antelope that I had become, I heaved on up the slope and towards a section of road that looked like a territorial border between this groups patch, and what could have been a sort of safety beyond.

There’s always a leader, or if not the leader, one who is prepared to go beyond the norm and into the reckless zone. And so it was no surprise when one of the boys, aged about 13, suddenly reared his bike up on its back wheel and peddling furiously in my direction and challenged me to do likewise. I suppose I could have got off the bike at this point and tried to engage him and his pals in a theoretical discussion about basic health, safety and sensible lifestyle choices. Or I could have complimented him on his sensational abilities, and suggested to him that a life in the circus was going to be his calling after his first two spells in borstal. But the reality was I just had a depressing sense of inevitability about his future. That positivism kept me going on through the group whilst he continued to perform his attention seeking wheelies, all the time trying to comprehend why the bald old bastard wasn’t meeting his not unreasonable territorial challenge.

I reached the next section of road, and sure enough the pack fell away and returned to their postcode (assuming the area had been allocated one yet?). Soon I had searched out a small road that headed back east, and with the mainline train track to my right, pressed on steadfastly and in the rather disquieting knowledge that there was at least half the distance required still to go. Lomas Road led into countryside and then an abrupt left on to Church Road and I was then winding down early autumn lanes. The countryside was pretty much what you’d expect in these parts. Gently rolling with a lot of greenery still in evidence, but with a subtle difference. Many of the fields contained small trees in lines, and the smell of late season fruits, mainly large red apples and on the turn sweet green pears, filled the air. At Blacketts Lane I picked up again on National Cycle Route 1, which I had somehow lost contact with somewhere between Iwade and the end of Sittingbourne. I wasn’t wedded to it, but it now made some sense to keep to it where possible until Herne Bay.

More fields and then a track beyond a large farm and then quite unexpectedly, I was on a path cycling south along the banks of another creek. This was a very attractive spot. On the opposite bank, as the river narrowed, a quay, what looked like a pub and a line of expensive and well-proportioned houses. At the southern end of the creek the path followed round a large marina and then into the village of Conyer. Very much a boating community, but if that was your thing, then certainly why not?

Out of the village and the route headed back inland, and then, just beyond the small village of Teynham Street, a thin cloud covering, and light rain! Not in the forecast that I’d heard about in the morning, but it didn’t last and only enhanced the sweet smells of the orchards that continued to line the road which then passed under the mainline. A left, now tracking the rails from the south side, and another mile where fields with lines of hops now dominated, and ended at a level crossing with the barriers down. After the train passed it was back over the line again and then grinding on narrow, tree-lined lanes that felt more like deep Surrey and which eventually wound into the suburbs of Faversham.

I couldn’t tell you now the route I took into Faversham but eventually I was cycling along what must have been the medieval market street backbone of the town. I was impressed. A wide street, with many architectural styles and periods represented. This was a town with character that had avoided a post-war mauling. Past the centre and down towards the town’s river, and there on the right, almost missed, was the old brewery. Not just any old brewery, but that of Shepherd and Neame. These days, their crisp, tasty and well-crafted bitters and ales are sold the length and breadth of the country. Even the tiny corner shop next to my flat does at least two or three of their products in pleasingly styled clear bottles (for only £1.99 too). But it wasn’t always so.

Back in the Dark Ages (that would be the 1970’s again), and over a frighteningly short period of time, a handful of huge multinational brewing giants had come to dominate the drinking industry, and in the process smashing the smaller independent breweries. In the south-east you would have to travel miles and miles to find a pub that wasn’t owned or managed through either Truman’s, Courage or Watney’s. And what you got for grog in these institutions was nothing short of tap water with some flavouring, that quite often, and if you were really lucky, smelt and tasted like chemicals that had gone unnaturally past their half-life date.

And so in order to avoid death by the most ordinary, intrepid journeys would be made out of south-east London and deep into the heart of Kent and Sussex, passing numerous pubs bearing the signs of the new power in town, but where the names of the old local provider could still be seen over the door. But, with persistence, or maybe it was just a blind optimism that overcame the dystopian state of affairs, occasionally there could be found smalls outpost that had avoided the all-seeing antennae of the conglomerates. If you wanted something really special, something that was so rare that you would be prepared to travel to the edge of the land and to pay very good money for the experience, you might have landed on a Shephard and Neame pub, and you would had found Nirvana.

Forget this nostalgia trip and lessons from history. The changes since then (with the caveat that if pubs continue to close at their current rate then this era will be looked back on as an age of mass extinction), have been so profoundly positive for the brewing industry that there probably hasn’t ever been a more diverse range of options and outlets, which of course includes my little corner shop. 😊

After gazing longingly at the old brewery building for a few minutes I then carried on, and followed some signs that helped me navigate out of Faversham and along a narrow road which the map showed as being part of the cycle route. Fields on either side and with the river further to the west. Defoe definitely did not go this way 300 years ago. Instead he headed south east and to Maidstone. From how I have read his account he had nothing positive at all to say about this area (in fact nothing at all from what I can recall), and after his inland diversion, re-emerged at Margate. That wasn’t in my plan and heading off in the completely opposite direction I eventually reached what on the map was referred to as a “Wks.” “Wks” covers a very wide range of industrial facility, but on this occasion, it was my second water treatment plant (aka sewage works) of the day. At the edge of the facility the track went into a field. I looked at the map, identified where I was and could see that National Route 1 continued through the field and then to a road beyond some trees. Venturing into the field, and trying to hold my breath, I only managed about 200 yards before, with memories of past misadventures on the banks of the Thames in remote places swirling through my brain, my nerve broke and I turned around and made my way back into the eastern fringe of Faversham, then eventually reaching a road leading out of town and back into the country.

So, let’s see if we can kill this saga off without too much more pain. Maybe in the time it will take to listen to Hunky Dory (look out you rock n rollers).

Through more fields and soon the lane came to a junction. I took the left option and down through Goodnestone and then to Graveney (don’t fear you pretty things, I won’t digress into 70’s cricket). Past Graveney the road descended towards the coast again and down into lowland marshes. Looked like a great spot for some solar farms I mused. Ah….it seems to have already been spotted and the locals are on high alert. Posters on various mountings telling the tale and pleas for mercy. I could feel the concern. The prospect of large areas of the marsh being turned into a layer cake of glass panels facing the sun would almost certainly galvanise any of us. But, maybe in the bigger scheme of things, and on the merry-cast orchard brow, it’s probably a god-awful small affair, and none of my business (or perhaps it is?).

The road eventually reached the edge of the land, and I stopped at the sea wall for a few minutes, mainly to take the pressure off my, by now, pained arse. I could see Whitstable to the east and so bite the bullet and got on with it. Time was pressing.

I know that Whitstable holds a special place for many people. I have to say I’m not sure I quite get it. Having been there once or twice, and aware of the Dickensian associations, I didn’t take any time out to inspect it further on this occasion. No obvious blue plaques here, but to be fair he has a shed load of them back in north London. My favourite is a sign on a 1950’s institutional building somewhere near Tavistock Square, that states that Dicken’s once lived in a building “near” the site. Many moons ago, some Kook had written next to it “So What?” It made me smile every time I saw it. It’s long gone, but the sign remains. The writings on the wall, and sometimes can be kind and gentle.

On from Whitstable and towards Herne Bay I don’t remember much. The sun was going down and the estuary was bathed in a subtle light where the groynes and the pebble beaches spoke of oncoming winter and stormy times ahead.

Through Swalecliffe, and at a point where Herne Bay effectively starts, one final brief stop to take a snap of a pub on the front which, unusually for these parts, had views both north and west, back along the beaches. Twilight time.

The end was near, and within another 5 minutes I had reached the point near the pier where I had been at on the morning of the 1st August at the start of the section between here and Deal. No time to dwell on any sense of achievement and so with a zigzag into the town, and then up to the station with three minutes to spare before the Javelin train (“David Weir” this time), pulled into the platform and then took me home.

Home was another couple of hours away, including the five further miles of peddling from St Pancras. Maybe it was time to reflect and acknowledge having completed the task. I opened the fridge, and there it was. Not planned as I rarely buy in ale. I lent in, and there in my hand a bottle of Shephard and Neame – Whitstable Bay pale ale. Just one. I sat outside and looked at the darkened sky. Just for a moment I was the King of Oblivion. Away, just for the day. Away.

And then it was time for Andy to take a little snooze.

41 minutes and 39 seconds (made it).

One thought on “Rochester to Herne Bay – 23rd October 2018”