Helvellyn

950 metres

3117 feet

Summer 2003 or 4

New Year Special – One From the Vaults

I was thinking about Scafell. Why had I never climbed it, wondering how on earth I would get the opportunity to do so now, and by extension reach the top of Cumbria. It had been bothering me, not least because I had climbed Helvellyn, a close second (or third as Scafell boasts two peaks, both slightly higher). But even Helvellyn was vexing me. It wasn’t on my itinerary, primarily because it wasn’t the top of Cumbria, but also because for the life of me my brain struggled to put together when and why I had been there in the first place.

It’s nineteen months since I started the county top challenge, and every week I’m finding out new things; not least that quite a lot of the on-line references, which on the surface look authoritative, often end up being unreliable; not deliberately, or due to casual research, but almost certainly because it’s a shifting shore.

My original list of counties, compiled just over a year ago from what, at the time, I assumed to be a reliable source, had included Scafell (which remains a legitimate target), in the county of Cumbria. My very large map obtained in December 2024 doesn’t disagree. So, some time ago, when a news article, or something similar, made mention of Westmorland, my ears started to twitch. Westmorland was a word I was certainly familiar with, but on checking the list it wasn’t to be found. I could have just left it like that, assuming that it was something along the lines of a generic term for a geographical area, but I’m beginning to find out that it’s best not to take anything for granted. I enquired further and soon discovered that Cumbria had been abolished in 2023 and divided in two, with Cumberland in the west and Westmorland and Furness to the east (are we keeping up?). And before anyone gets too nostalgic or sentimental about the demise of the ancient county of Cumbria, it ought to be noted that it (Cumbria) only came into existence in 1974 following the combining effect of, err… Cumberland, Westmorland, parts of Lancashire (!) and, (I can’t even believe the Yorkies let this happen without another civil war), part of the West Riding of – yup – Yorkshire! *

All these political shenanigans aside, once it had become clear to me that Westmorland and Furness was now a thing, and was added to my ever-lengthening list, I realised I had acquired a mighty peak by default. One could say of course that this is exactly the sort of bewildering quirk of the game that makes the exercise entirely meaningless. And, of course, one must agree, but hey, when I had climbed Helvellyn over twenty years ago, it had been an achievement, and by only a matter of a few metres is just a tad shorter than Scafell. It deserves to be a county top, and I am very grateful for that too.

Another notable claim to Helvellyn is that to the best of my knowledge it’s the only county top I have managed with both my son and daughter (with the possible exception of the City of London, which, I have just noted has disappeared from my latest definitive list).

I am unclear on the year, but from the information I wrote on the cover of the pack of the slightly disappointing snaps I took at the time, it was either the summer of 2003 or 2004. My children were teenagers and had been packed away for a week (voluntarily I should add) to a scout adventure centre at a place called Lochgoilhead, a remote location to the west of Loch Lomond in Scotland. The Scouting movement can divide opinion, but I don’t have a single bad word for the inner-city group that both my kids attended. Without any shadow of a doubt, it stretched them and cemented in them a desire for exploration, a sense of justice and a “can do” attitude.

Having said all that, whether they were thrilled by the prospect of another few days in the great outdoors under canvas, with their dad, at a campsite next to Ullswater only they can say, and I don’t intend to ask them now.

To reach the top of Helvellyn required me to do the following. I drove from London to Glasgow, spending a night or two with my Scottish relatives and brushing up on the lingo, before heading over the Erskin bridge into the Highlands, up Loch Lomond to Tarbet and then cross country to the remote settlement of Lochgoilhead. After meeting up I remember there was time for a march up one of the nearby braes to take in the breathtaking views down Loch Goil. The next day, with the rest of the squad, and the selfless volunteers who had made the whole thing possible, taking the long minibus journey back to London, I abducted my own and spent the rest of the day journeying down to Side Farm campsite, just to the east of the small village of Patterdale on the banks of mighty Ullswater in the Lake District. **

Our stay was for just three nights, and from memory the weather was kind. At the time my daughter would have been around 12 and my son 16. I recall that on the first full day we hired bikes and cycled on mountain trails up the east bank of the lake. About an hour in, one of the tyres on my son’s bike burst, leaving him to have to walk it all the way back. He seemed cheery about the prospect, probably delighted to have an excuse to spend some time apart from his sister and annoying dad. And who could blame him?

I can’t say with certainty that I can remember the exact route to the top of Helvellyn the following day, but I have an Ordnance Survey (Explorer OL5) map dated 2002 which fits into the likely dating, and a handful of photos, so here goes.

We drove the short distance from the campsite into Glenridding parking up near the large hotel… or did we? Yes, I recall that small boats lined the lake, dancing on the waves nearby… or did they?

Whether either of the kids saw this as an adventure, or just a task that needed to be completed to keep me happy, only they can say, but full credit to them, once we set off inland through the village on Greenside Road, they were clearly committed to the cause. The weather was largely overcast but warm. Ideal conditions.

We continued up Greenside Road until crossing over a small bridge over a stream and then onto open countryside, with Helvellyn in view at all times. I confess that at this stage it does get a little hazy, but I think we must have taken the main footpath running southwest and to the north of Glenridding Beck.

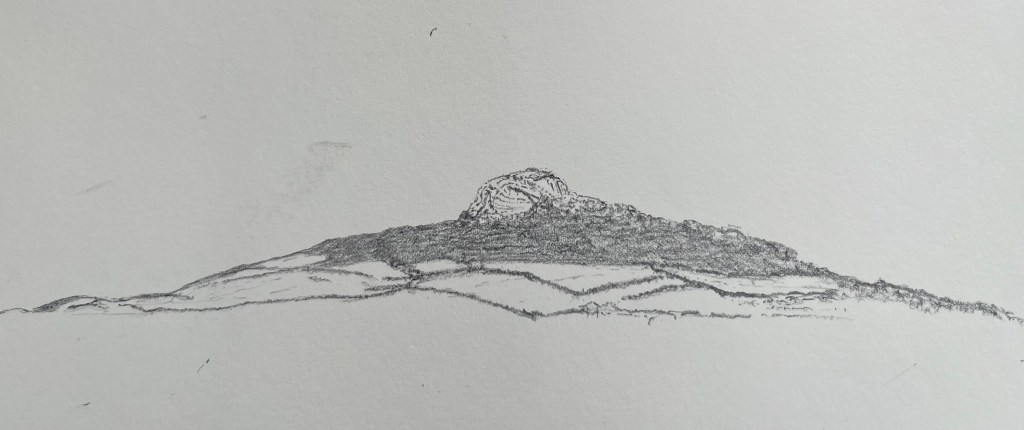

Looking towards the beast, with my daughter dressed completely inappropriately for upland hiking and asking if we were really going to go up that?

From cross referencing the photo with the OS map, I’m fairly sure that this photo was taken where Rowton Beck meets Glenridding Beck. The idea of taking on one of the almost vertical routes directly to the top was a non-starter.

We followed the main path along Glenridding Common, and then started the zig zag climb up the slightly less challenging slope to the right, and eventually along the long straight path from Raise summit to the cairn at Whiteside Bank.

Looking back along the route from Whiteside Bank, with Ullswater beyond

Before I continue this reconstruction of what is now a somewhat ancient journey, a brief aside. A couple of days ago, I’m watching BBC News and up pops an article about the Patterdale Mountain Rescue Team trailing robotic legs. My eyes and ears were immediately alerted and for the next minute I watched how these carbon fibre leg braces, with some sort of battery attached, positively hurled the wearer up the hill paths. It seems that the number of call outs over recent years has escalated and the equipment allows the already stretched service the chance to get to their target more quickly and more efficiently, particularly as they also have to carry heavy packs. I couldn’t quite work out how they worked, not least because one would still be subject to lung capacity issues, but from what I saw they looked like the very fellows (as Billy Connelly once said) and may have to check them out for myself as the arthritis kicks in further.

What a beautiful sight – Helvellyn on the Beeb and in the safe hands of the volunteer rescuers

The associated message within the article was the significant increase in people rocking up in the wilds without the right equipment and then getting into trouble. Nothing particularly new in that message I guess (it’s an age-old issue) but from what I have seen recently on social media, it doesn’t surprise me. I have been getting lots more feeds showing people taking walks and hikes in remote locations and getting positive responses (check out Eddie Cheee in Scotland – he’s brilliant). I think they are great, especially when they show places I have known, but it’s almost inevitable that others will follow in their footsteps, many poorly prepared and equipped. And, when I have looked at what my kids were wearing when we climbed Helvellyn, I am the last to moralise on the subject. T-shirts and shorts! What was I thinking?

Back in the past, underequipped and irresponsible, we completed the next leg to the summit. This required trekking across the tricky ridge that would eventually lead to Lower Man (a distinct summit in its own right just to the north of the Helvellyn summit)

A random shot that could have been taken on the route towards Lower Man and possibly looking south-west towards Thirlmere, or north, or east-southeast, or, but honestly, who knows?

We eventually reached the top of Helvellyn, a relatively flat area of land but with the best views in town. I have some pictures of the kids looking suitably heroic (which of course they were), but for jolly good reasons (i.e. they definitely haven’t given me permission) here’s one of me to prove the event (heavily disguised of course as I haven’t given myself permission to post this into the public domain, primarily on the basis that my receding hairline was now in full retreat and the sideburns were entirely unnecessary).

Used for evidential purposes only but note that I for one was wearing something that could have kept out the rain for a few moments.

Suitably refreshed and slightly intimidated by the weather system pushing in from the direction of the Irish Sea, we made our move down. Easier said than done.

Hmm… could be trouble ahead. Looking south-west

Anyone remotely familiar with Britain’s upland landscapes will know that Helvellyn is famous for its most distinctive feature. And here it is:

This is Striding Edge – no messing!

At the sight of Striding Edge, all jagged rock and with the land falling hundreds of feet away, potentially catastrophically, on each side, I recall suggesting a retreat back along the way we had come. It transpired that I was talking to myself. Both my children had left me at the top and were now clambering, skipping and jumping down and along the precipitous path towards, in my mind at least, almost certain referral to the authorities. I think I may have shouted some words of advice. “What the @*&% are you doing?” comes to mind, but it was probably more along the lines of “slow down and wait for me”.

A little blue dot at about 100 metres, and just to the left of the thin path, indicates my feral son. I can just make out three people to the right of the path clambering over the rocks. The whole scene just shouts, DON’T.

Striding Edge is a classic example of an arete (strictly speaking, being a French word there ought to be an ^ above the middle e, but you get the idea), a narrow ridge dividing two valleys, and brilliantly Striding Edge is the first image to be seen on Wikipedia when you search the word. As striking and visually impressive as Striding Edge is, it’s about 400 metres in length and although at times you can follow a safe’ish path, quite a lot of it requires clambering up and down awkward rock formations. Great fun if that’s what you’re after, but nerve wracking if you’re responsible for two minors (technically at least). My granddaughter, just nine, has recently been bitten by the climbing bug (nothing to do with me I should add), and from what I’ve seen of her on the climbing walls she’d boss Striding Edge.

We did survive Striding Edge and eventually made it to the Hole-in-the-Wall, a dry-stone wall, unsurprisingly I suppose, where paths intersected and forming a boundary between the up and low land. I have a clear memory of arriving at this point and looking at the surrounding landscape. Maybe it was just a profound sense of relief that we had made it this far and were well and truly on the home run.

At Hole-in-the-Wall looking back up towards Grisedale Tarn (out of sight) and Fairfield Peak rising to the left, and Dollywaggon Pike to the right. BTW, I’m prepared to be contradicted on this if challenged.

We took the descending path over open country and covered the three or four kilometres back to Glenridding in less than an hour, and then on to the campsite for a last night under canvas. London and reality were calling.

Last evening on site and the weather on the turn

I started this by saying I had been ruminating on why I hadn’t climbed Scafell. The reason is simple. I haven’t been there yet, and to be honest, I’m not sure I will (from what I have heard it’s supposed to be tougher than Helvellyn), but if it happens or not it’s unimportant. What is important is that once upon a time my son, my daughter and I made an effort and reached the third highest peak in England. Hallelujah…

* A fascinating detail, particularly if you’re a Scot (I’ll say no more), when the Normans invaded most of what we think of as being Cumbria (and for want of a better description – other terms were available then), it fell under the governance of the Principality of Scotland. It did not feature in the Doomsday Book. By 1092, just 26 years after the invasion of England, William II, unable to resist the urge to invade, put paid to that. $£@%*&?’s!!!!!!

** In my old day job, I happened to manage numerous council blocks located in central London that bore the names of both Patterdale and Ullswater, along with other large blocks of flats named after other locations in the Lake District, many (having now looked at the map again) in the Helvellyn area. When they were built, just after the second world war, the lobby of each block had a large ceramic painting set on the wall that depicted the area it had been named after. From memory, by the twenty-first century all but one of these fine municipal works of art remained, the rest having fallen victim to refurbishment schemes or vandalism. I used to wonder what people living in these blocks must have thought of the daily reminder, as they passed through the lobby, that they lived about as far away as possible, physically, culturally and economically from the Lakes, and the uplifting images that they were confronted with. Many may not even have noticed. Some might have shrugged and cursed the irony, whilst others might have been inspired to jump on a train from nearby Euston station, and head north to explore.

*** Robotic legs. They’re the future.