I hadn’t seen it coming, but when it did, I had to confront the beast. The Unitary Authority! But before we meet the beast, time to reflect.

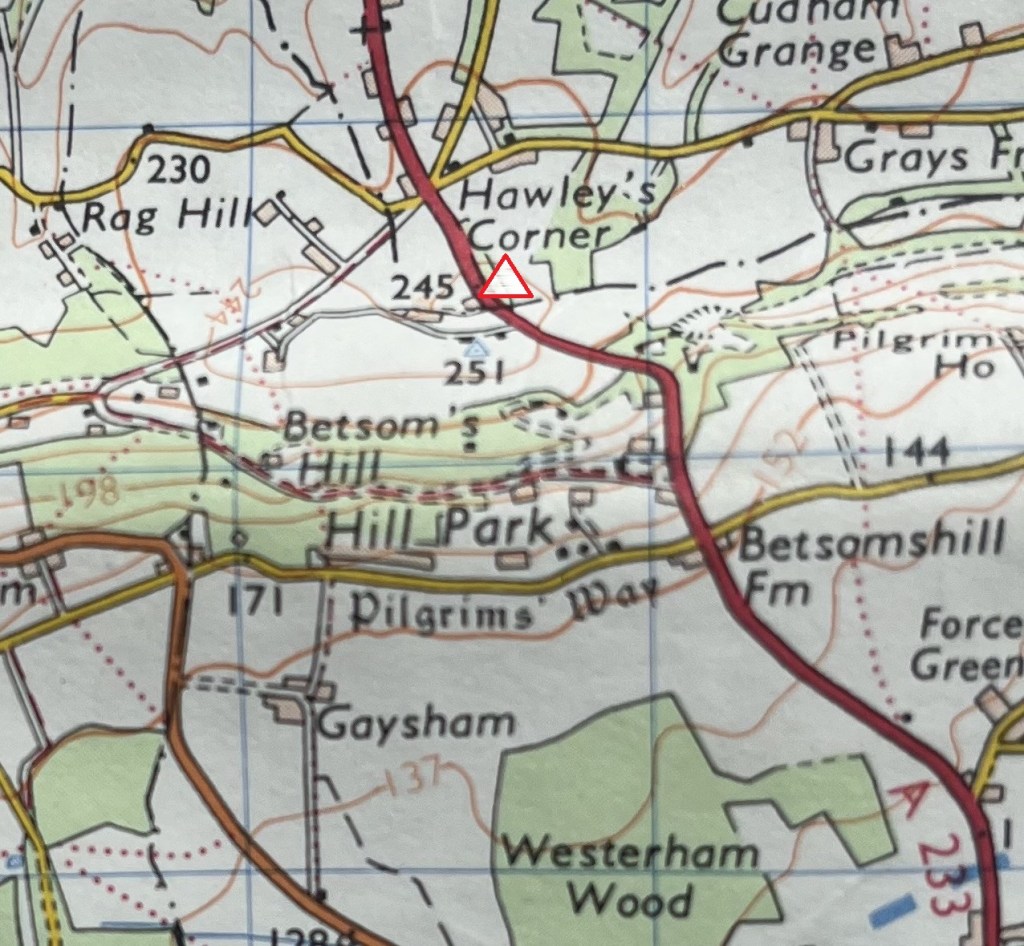

On the 10th May 2024 I parked up in Westerham, Kent, marched north out of town and fifty minutes later was standing by a wall, looking across a field where my very basic research had established the highest point in Kent. Betsom’s Hill. It was a small start, but as the months progressed, further counties’ highest points were reached, either on foot, or drive by. I’d have liked to have done one on the bike, but that may remain a pipedream.

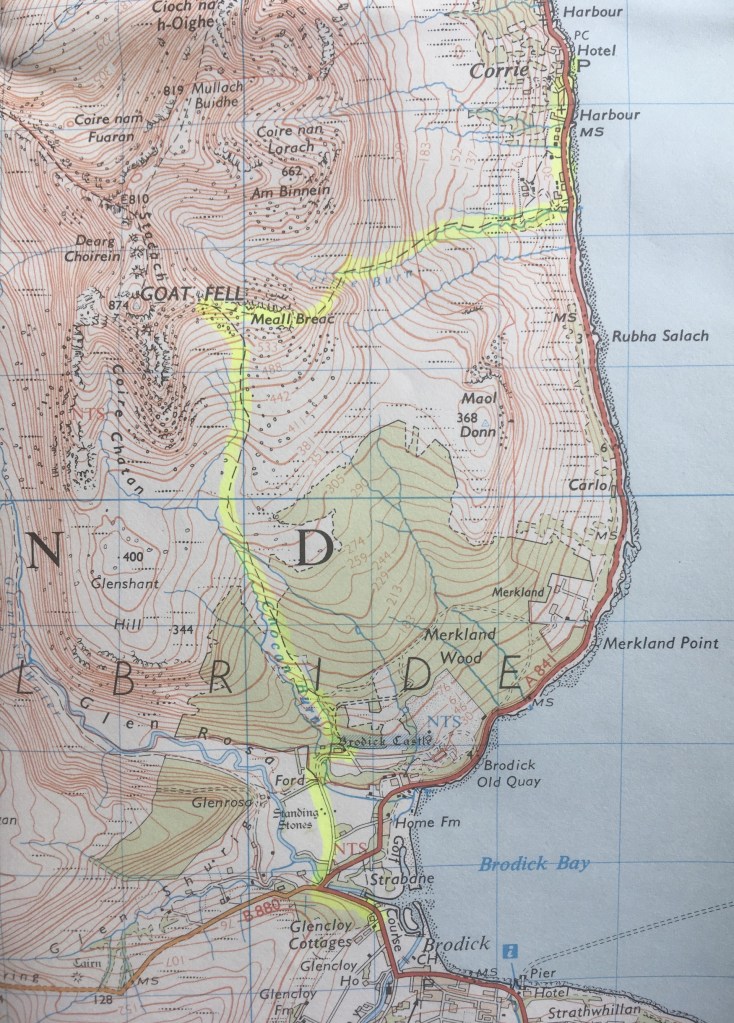

I had initially been inspired to take up this arguably pointless activity after a climb to the top of Sugarloaf Mountain in Monmouthshire, with my daughter and her partner J. After the climb, in March 2024, I read that Sugarloaf was the highest peak in Monmouthshire, and I realised that there might be other opportunities, either by chance, or by deliberate choice. Indeed, as I began to research the topic, I realised that over 66 years I had achieved some already. Just a few weeks later, again with my daughter and J, we were standing at the top on Ben Nevis, in a thick, cold cloud. It didn’t matter, I had done it once before thirty odd years earlier with my son, on a glorious Highland day. Just getting there had been an adventure. On the way back home, and due to far too casual planning, I narrowly missed out on the highest point in West Lothian, but three days later I drove to the highest point in Nottinghamshire.

Early on I realised that if I was going to take it a bit more seriously, I would need to compile a list of counties and establish the highest points. With the immense power of the internet this would surely be an easy matter and completed in a couple of hours.

Days later, and despite numerous searches, I hadn’t yet found what I considered to be a definitive list of British counties. Eventually I settled on a list that, from all the indicators, felt about right. It contained all the counties in Wales, Scotland, England and Northern Ireland. I created a table and placed each county in alphabetical order. Whilst I had included the six counties of Northern Ireland, but with no friends or relatives to justify a visit, I rationalised that it was unlikely any would be trod. The list understandably included Greater London and Greater Manchester.

Over the following weeks I researched the highest points and began to log by county, nearest place and height. What this process began to reveal was that I wasn’t alone. I hadn’t been naive enough to think that I had come up with an original concept, but as the weeks went by, I came across more and more sites written by others (all men so far) who were committed to the cause. In due course it became apparent that far from being a micro niche activity, after angling, it was almost certainly the largest mass participation leisure activity in the country. Oh woe…!

Well, it was what it was, and I was enjoying going to new places, finding out more about areas I may have been to before, but more interestingly, the places I had never been to before and, up until that point, had never intended to go to at all (Warwickshire being the best example so far).

Ebrington Hill, at the western most point of Warwickshire, was the last to be achieved in 2024. Winter set in, and that involved it raining almost every day for the first few weeks of 2025. I wasn’t going anywhere, not least because the roof had surrendered to the elements and I was going to have to dig deep to get it fixed.

To fill the vacuum, I went online and purchased a very large and basic map of the UK, divided by county. Simple, but beautiful in its own right. Once I had carefully mounted it onto a sheet of ply, cut from a much larger sheet that I left in B&Q when I realised it wasn’t going to fit in the car, I could now sit comfortably and gaze lovingly at the entire UK and contemplate options for the coming months. When I wasn’t hypnotised by the map or watching steady rain on the window and getting more and more anxious about the arrival of the scaffolding, I started to research the underlying geology of each of the heights. I’d previously downloaded the British Geological Survey’s Geology Viewer (BETA), and this amazing work of science, art and technology was all I needed to not only establish the underlying geology, but also accurately pinpoint the highest points (believe me not everything published online about highest points is correct or accurate).

In late March 2025 I set off for a few days in Bristol and the West County. Before leaving I sat down and took a close look at the enormous map.

An Enormous Map

The good news was that I would be passing through the north of Hampshire, where Pilot Hill marked the county’s highest point. The City of Bristol was also on my list and would be an easy win. But, looking more closely at the region around Bristol, it became clear that any previous assumptions had been misplaced. Somerset had been on my radar, but the map, published in 2014 was showing far more “counties’” than I had expected, not least South Gloucestershire.

Back in September 2024 I had climbed Cleeve Hill in Gloucestershire and had assumed it had been a done deal, but no, not according to my map. It was a mystifying blow. What had I missed when I created my original list? Turns out that what I had missed was the huge change in the political landscape that has taken place in the last half century. Of course, I knew that some of the old historic counties had long gone, Middlesex and Caithness for example, but it had completely passed me by that much of the country, (especially England) had since been subdivided (presumably due to shifting demographics, or let’s be a tad more cynical, gerrymandering?).

What my planning strategy to visit the West Country had revealed was another entity, with, from what I could glean, similar powers to traditional counties – the Unitary Authority (UA).

On one level this was deeply troubling. At the time I didn’t have the gumption to count how many additional regions were about to enter the fray, but a brief look suggested at least some tens more. But on a more positive note, this now offered up many more opportunities, not least the many Unitary Authorities that now presented themselves for inspection over the coming days. South Gloucestershire for starters, but also Bournemouth, Poole, Christchurch, Southampton and Portsmouth, that I would be passing through on my drive home a few days later. And that didn’t include North Somerset, and Bath and Northeast Somerset, which, whilst being near Bristol would have been too much to attempt during my tour.

Over the last few weeks of the self-imposed calendar year (May to April), I started to update my list of counties by adding in the Unitary Authorities. This revealed other troubling difficulties. Again, working from information on the internet, inconsistencies began to emerge. For instance, my map had shown there to be three UA’s sitting next to each other in Dorset; Poole, Bournemouth and Christchurch. This had led me astray when I had passed through the area on my way to Portsmouth. The reason being that in 2019, long after the publication of my map, these three authorities had merged to become BCP Council (Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole). Shucks!

What this confirmed, had I not already known it, was that whilst the map was helpful, it was already out of date, and couldn’t be relied on to provide a definitive list. Again, I faced the difficulty of trying to locate an accurate list of all the UA’s. In the end I decided to opt for the information on Wikipedia, which from what I could tell, was likely to be as accurate as anything.

Needless to say, my list has expanded exponentially and is likely to keep me occupied for some time to come.

The UA/County, West Country complication

Local authority elections were held in England in May 2025. I spent most of my life in London but now live in East Sussex. I am pretty sure that when I was growing up the county of Sussex was a “thing”. But I am wrong. Sussex has been divided between East and West Sussex for centuries, and maybe as long ago as the 12th century. 1889 was the year that saw them fall under separate council governance, and in 1974 this was formalised following the Local Government Act of 1972. Now what constitutes the entirety of old Sussex consists of East and West Sussex, and the Unitary Authority of Brighton (yet to be topped).

Along with all residents of voting age in all three authority areas I was unable to vote in May. Along with several other areas across the country the government paused elections whilst a period of consultation took place to decide on whether the whole of the county should come under a single authority. Because the outcome is due in the next year or so, it was decided that it would be too expensive and impractical to hold elections for councillors who may, or may not, be out of a job in just a few months. Not only could that see the end of East and West Sussex and Brighton, but potentially lower tier authorities such as Lewes, Worthing and Hastings.

Sussex covers a massive area. It stretches from Camber Sands in the far east, East Grinstead in the north and to Wittering Sands in the far west. It’s approximately 90 miles from east to west along the coast, and, just for the record, takes bloody hours whether by road, or even worse by rail. And, apart from the Channel, what these places have in common is probably restricted to the consumption of the rather fine Harvey’s Best. Of course there is an argument that in an age of austerity, and where confusion presumably reigns over the plethora of computer and information systems that must operate, combining the authority into one, would, in a nutshell, bring obvious efficiencies of scale. I can see some benefits in that, and am yet undecided, but my gut instinct is that if it is agreed, local democracy will be stifled. At a time when there appears to be a thirst for more localism, this feels to fly in the face of that process. A single authority and an elected Mayor running this huge, and hugely economically, politically and geographically diverse area? Hmm. I’m not so sure. I certainly need to give it more attention. At least (except for Brighton, which I guess I may need to do pretty sharpish) I have stood on the highest points of both East and West Sussex.

My last walk before the end of the calendar year took me on a train ride into Kent, and from Snodland Station up to the top of the Medway Unitary Authority (yup, this wasn’t a place I had anticipated visiting until recently). That day marked the first day of Reform UK gaining control of Kent County Council (not subject to any consultation on a single authority). Hmmm, well we’ll have to see how that goes. Their first act in office was to remove the Ukrainian flag at County Hall. Gesture politics, tokenism, who knows but feels like Vlad the Invader has just got his little tippy toes on the beach at Pegwell Bay.

Before I end this introspection, a word of warning to anyone thinking of putting on the boots and pursuing the county tops (and UA’s, and Metropolitan Districts – Oh, did I not mention them?). Speaking of Sussex and putting it back into the context of this arguably futile pastime, whilst looking at some of the many blogs and websites by other committed county toppers, one in particular caught my eye. I can’t now remember how I got to Richard Gower’s site, but not only was he going after all the current counties, he had gone so far down a wormhole (and I say this with affection), that he had completed all six of the ancient “Rapes of Sussex”. These ancient administrative areas divided the county, running west to east, into six areas: Chichester, Arundel, Bramber, Lewes, Pevensey and Hastings. It’s fascinating stuff, but it’s a cause too far for me. It may be that as the sands of time catch up with me and I find myself less able to travel, visiting their respective highest points (and as it happens, I have already unwittingly done at least two of them), could become an attractive option. I’m also imagining that if the rest of the country was at one time divided into these ancient domains, the quest would become an unending toil in every sense. All that aside, I must take my hat off to Richard Gower. It’s a pukka site. **

Just a final note on the website (if that’s what it is?). It’s rubbish. Moons ago I completed several bike rides along the coast from London, around Kent, and most of Sussex, and after each wrote up some notes on a Word document. All very well but once done, would I ever revisit them? My daughter had started posting some things on a website/blog. I liked the appearance, and as importantly I could read them on my phone without the word blindness that normally prevails. For no reason, other than I had heard of it, I started to transpose the words from Word to WordPress, added a few photos and some infantile art, and began to post each leg of the bike journey under the perhaps less than original title of Pier to Pier. *** Whether or not people read the posts (on one day I had 15 odd “likes” from what I had to assume were “bots” and emanating out of the US, given that it appeared nearly all were teenage females whose likely interest in a cycle ride round the Isle of Sheppey was deeply suspicious), didn’t concern me. What I gained from it was the thought process and then, whenever I chose, being able to read them on my phone, or any other device, to remind myself of what I had done.

I’ve been writing since I was ten (to paraphrase Marc Bolan). Immature diaries, essays, short thoughts on bands and gigs, futile attempts to write a book, and then over thirty five years, millions upon millions of words in memos, letters, works order tickets, emails, reports, presentations, minutes and many moments of long reflection when things might be getting too much, and when self-articulation through pen and paper, or keypad and screen, relieved the pressure; like lancing a boil. It may sound a bit contradictory, given that each escapade I publish an account online, but I write (primarily these days) for myself. The accounts reflect how I was feeling at any one moment, what I might have been thinking about, if there were local or international events that might influence the narrative and any significant landscape or features worthy of note. They are not intended to be a fully formed guide to other intrepid walkers, so beware should you choose to make one of these ascents solely based on one of these reads. Unless it’s obvious or easy, always take a map, and of course a phone (and keep in mind that a phone can run out of battery or connection, a map never does).

None of the above justifies the utterly useless presentation. I have honestly tried for hours to create a landing page where different threads and menus are clear to see (like everyone else’s), but I’m no further forward that I was years ago. The next time anyone younger than me visits, I’m going to have to collar them. In the meantime, what it is will have to endure.

The music – well that’s just an afterthought if something about the day has brought a tune to mind.

So, having walked to the top of Betsom’s Hill, and with some more county tops on the near horizon, so to speak, it made perfect sense to commit each experience to the page, and then the world.

I discovered one other key detail, and as such see the need to advance a precautionary slice of advice. Some weeks after climbing it I discovered that Sugarloaf Mountain was not the highest point in Monmouthshire, it’s the highest peak. When I found this out and given that it had been the motivation to start this project, it came as a bitter pill to swallow, not least because at some point I’m going to have to go back and climb to the actual highest “point” – Chwarel y Fan, which sits a few miles to the north of Sugarloaf. Well, at least now I know. Here’s coming for ya..?

* https://geologyviewer.bgs.ac.uk/?_ga=2.58458858.1363630663.1720815697-999374144.1720815697

** https://www.richardgower.com/blog/sussexrapes

*** https://elcolmado57.co.uk/2018/10/16/pier-to-pier-a-coastal-caper-with-occasional-calamities/