Uffington Castle

262 metres

860 feet

14th September 2024

In the Footsteps of Alfred Watkins – Part 2 – Chalk Art and Car Parks (Part Two)

As I drove carefully along Station Road towards the B4507 at Kingston Winslow, to the east of Swindon, I knew with absolute certainty that I had never been anywhere near this rural delight before. I was returning home after a few days exploring and contemplating Alfred Watkins theories on the possibilities of ley lines in the Hereford and Worcestershire area. Whilst I was left unconvinced, his 100-year-old book “The Old Straight Track” provided a charming account of a bygone ideal. I was now heading towards a point of reference that was oddly missing from his account, the Uffington White Horse (the nearby “castle” being the highest point in Oxfordshire). For once, it was a glorious day.

A narrow road to the south of Woolstone took me up to a busy National Trust car park. At the pay and display machine several confused people stood around trying to figure out the least complicated way to part with their money. My heart sank when it was my turn. The machine refused to give me an option to pay by card (unless I was a member?). Having not quite recovered from a brutally traumatic experience at the National Trust car park at Beacon Hill in West Sussex, it was with a deep sense of foreboding that I called the pay by phone number. The mind-numbingly awful, computerised voice was hideously familiar, and when it asked for my PIN number (you know that number that’s so embedded in your brain that it is instantly memorable every time you use it, once or twice a year), I knew I was going to lose another valuable part of my life to the task. And I did and I’ll say no more.

On the plus side, the cold blast from the north that had dominated the week had subsided, and it was now warm and sunny enough to wear just a T-shirt and light jumper. Bliss. After the frustrating pay by phone debacle, I left the car park through a gate to the east and was immediately on the open chalk down. The hill fort was a few hundred metres up a gentle slope. This was going to be over a tad too quickly.

As I reached the lower ditch a track headed away to the south, and keen to stretch the legs I flanked round the structure, watched a kestrel and then two red kites patrolling the farm fields nearby, and then met up with the Ridgeway path to the south-east. There was no point putting off the exploration of the hill fort any longer. A short walk north and I was at the trig point sited at the eastern point of the massive earthworks.

At the top already..

The trig point stood at the top of the eastern rampart of the deep ditch (the terminology used here is likely dubious). The earthworks on the other side of the ditch seemed to be marginally higher, though surely that was just a trick of the eye. I clambered over and at the top was able to get the full view of the ancient structure. I have no expertise in these areas, but even to my untrained eye, the huge expanse of ground that lay within the single, broadly circular ditch and earthworks, was quite obviously not a defensive structure. Whilst the ditch would have been deeper and the earthworks higher, to describe it as a castle or hill fort is fundamentally misleading, but possibly increases tourist numbers. Even imagining a wooden fenced structure around the perimeter left me in no doubt that trying to defend this huge area would have been a completely pointless exercise.

Keen to guarantee I would stand at the top of the county, and extend the stroll, I decided to walk the full circumference. As I ambled along the rampart, I mused on what its purpose might have been. It reminded me, in size and shape, of a cricket ground. A proto-Oval or Lords perhaps. As there is absolutely no evidence (yet), of cricket being played in the Iron Age I ruled that possibility out, but the idea that it was an arena of some sort persisted. I wasn’t alone in beating the bounds, and as I passed couples and families out enjoying the day, the same observation kept cropping up in conversations. “What an amazing view.” Despite the relative lack of elevation, on a stunning day like this, they weren’t wrong.

On the ramparts looking west towards Swindon

Having completed the full circuit I chose to do what no one else was doing. I left the earthworks and walked in something of a direct line to what I figured was the centre. The ground seemed to rise slightly from east to west which meant that until I got to the approximate centre it wasn’t possible to see the western ramparts. The untidy vegetation had been left to grow, which further ruled out the possibility of cricket being played, at least until the first cut next year. An enormous mushroom emerged from the undergrowth, reminding me that what we buy at the local supermarket is a pale reflection on what you can obtain in the wild. I was tempted to pluck it, but decided to leave it in the ground as I would never get through it.

I headed northeast and towards one of the three or four entrances. A small metal plaque explained a bit more.

Keep off the grass.

Beyond the embankment a sort of path took me to the area above the White Horse. Understandably, it was roped off, but trying to pick out the chalk detail was easier said than done. I think I was able to make out the head and neck, but it would have to wait until a later inspection of the photograph I took to get a better understanding.

Who knows? Dragon hill below right.

Below, a beautiful sweep of land with a dry valley and a flat-topped hill made for an impressive vista, and invited the observer to descend, maybe for a better view of the horse. A path continued above the carving and then gradually descended with another stunning dry valley to the right.

A classy dry valley

The path eventually crossed a narrow road and continued to Dragon Hill, with steep steps leading to the top. Whilst a natural feature, the top has been flattened. The story goes that George (he of the Saint status) killed a dragon here, and that the blood of the dragon poisoned the ground at the northern point, so now no grass grows. That’s one explanation… I guess. I mean, I just about get the dragon thing, but the idea that George ever came to these isles is clearly prosperous. I was drawn to the patch of bare chalk. Like thousands of people every year, and no doubt down the millennia, it’s about the only spot where you can get any sort of view of the White Horse. And perhaps that’s another explanation for the bare patch? But, even at this point the view was limited.

You still have to use your imagination. The bare chalk in the foreground remains a mystery, apparently!

I left the hill slightly disappointed. It was obvious that this exceptional work of art wasn’t going to reveal itself when up close and personal, and that being able to see it in its entirety was probably only possible from the Vale to the north. On the plus side, a chalk ridge, its scarp slope wave-like notches formed in the ice-age, curved away to the west to dramatic effect.

The Manger. I suppose it could be a dragon’s tail. I might be onto something.

Retreating from Dragon Hill, and avoiding puddles of dragon’s blood, I followed the narrow road back towards the top, taking in the views at every opportunity. Two kestrels, unperturbed by my presence, patrolled the field just below me.

Halfway up the hill and looking back, it was just possible to get a more complete view of the horse.

Ah yes, that’s better!

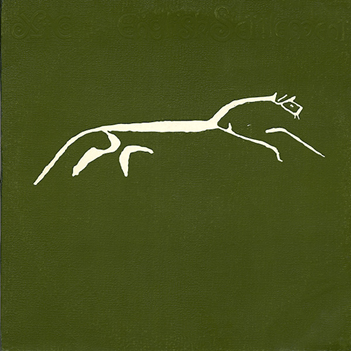

The image is very familiar to most of us, and unquestionably it is a work of art. The sense of motion is palpable. The people who dug it out of the soil were not only deeply artistic, but also observational scientists. It wasn’t until the 1870’s that a photographer (Eadweard Muybridge) was able to demonstrate convincingly how horses moved their legs whilst galloping (and I’m not going to attempt to explain it here), but you only need to look at an image of the White Horse to see that the ancients had already nailed it.

Unless it’s supposed to be a hare?

Back near the ramparts I headed towards a plinth. A circular steel directional plate lay on top. The third toposcope in four days. One of the many arrows pointed northeast towards Muswell Hill at 46 kilometres. I hadn’t realised I was so close to London, and was no less mystified that they had chosen to highlight the home of the Kinks rather than Highgate or Hampstead. Well, it was a mystical place, so I guessed there must have been a reason. *

I drove back down the steep road from the National Trust car park, and onto the B4507. The amount of roadkill here was extraordinary but, to be fair, it was of the highest quality. Mainly pheasants! I heard recently that the entire biomass (total weight) of all game birds reared for the purpose of being shot in Britain is greater than the entire biomass of all our wild birds. I suspect that’s pretty shocking, but I don’t know for sure. Either way, these dead ducks had skilfully managed to avoid death by traditional lead shot. Whether taking a broadside from a Range Rover Defender is a more, or less, dignified way to die is hard to say, but as I rounded a bend in the road I had to brake sharply in the old Ford to avoid terminating a buzzard that was lazily dining off the King’s asphalt table.

A moment or two later one of the seven thousand plus tracks on my iPod kicked in. Given the Muswell Hill reference at the toposcope, I had been chewing over which (of surprisingly many), Kinks tracks could neatly bookend this quintessentially English piece, but with the windows down, instantaneously the song randomly playing on this high, blue-skied late summer’s day, just outside Swindon, was entirely perfectamundo. It wasn’t Elgar, but it was XTC.

* The Muswell Hill indicated at the toposcope lies beyond Oxford, in the middle of nowhere and certainly nowhere near the Clissold Arms, East Finchley.

Footnote on the White Horse

The White Horse at Uffington is unique. But Alfred Watkins failed to mention it in the Old Straight Track. Having re-read his theories (after something of a fifty-year interregnum), it’s now very easy to pull apart most of his examples, not least because the science of archaeology has since been transformed.

Nevertheless, given Alfred was so convinced he was onto something significant, not to present some evidence of ley lines associated with the White Horse seems inconsistent, not least because whilst not on his doorstep, it wasn’t a million miles away either. One of the examples he relies on, more than once, is the Long Man of Wilmington on the north slope of the South Downs, between Eastbourne and Lewes (and many, many more miles from his home). It’s an impressive feature on the landscape and can be seen for miles. Watkins contended that the figure, standing erect and holding a staff in both outstretched hands, was conclusive proof that the pre-Romans were skilled surveyors and that the Long Man evidenced how they would have created the leys.

At the time you certainly wouldn’t have been able to write this thinking off, until along came the pesky archaeologists with their fancy new dating techniques and discovered that it was only a few hundred years old! That was in 2003. Just a few years earlier, and before all this science stuff got in the way, two of Watkins’ apostles, Nigel Pennick and Paul Devereux, published their own updated money maker, Lines on the Landscape. Rather stupidly, at the time being part of a history book club that specialised in slightly off the planet theorising, I bought it. It must have been a lean month subject wise.

In this book the authors go one step further than Watkins. They do indeed reference Uffington, detailing a supposed ley line that passes through (interestingly not the middle) of the nearby hilltop fort. Whilst they mention the White Horse, it’s only noted as being “nearby.” That, though, is very important. On the same page they also illustrate ley lines that pass through the Long Man of Wilmington, and a ley line that passes “near” the Cerne Abbas Giant in Dorset. It is possible that the rather alarming looking Cerne Abbas is somewhat older than the Long Man, but using the same contemporary dating techniques, applied just a handful of years after their claim, it too, at its oldest, is probably Anglo-Saxon. Given what we now know about the age of these landmarks, and without giving Pennick and Devereux much more undue attention, it’s probably time to lay the leys theory to rest. It’s clearly a busted flush.

Yet the Uffington White Horse, an abstract work of art, etched with passion and care into the landscape, is very actually pre-Roman. Since visiting, I have hardly stopped thinking about it. It has been regularly maintained ever since its creation over two thousand years ago, including during the Roman period and the Dark Ages. If it had been left to its own devices for just a couple of decades throughout this time it would have disappeared for good. It has a story still to tell, and I have an ominous feeling I’m about to disappear down a labyrinthine rabbit hole (and my middle name is Alfred too!). My book, The Uffington White Horse, Thoroughbred or Carthorse in the Neolithic Astral Plane, will be published (honestly, it will!).

One thought on “Cresting the County – Oxfordshire”