Lewesdon Hill

279 Metres

915 Feet

31st March 2025

The Eight Thousand and 39 Steps

Having spent the weekend with my daughter and her partner in Bristol, and having successfully claimed Hanging Hill in South Gloucestershire, rewarding myself with a strong coffee at the Swan Inn at Swineford, I drove south down almost vehicle free roads through Somerset, then east Devon and eventually into Lyme Regis in Dorset. A couple of nights booked in the Nags Head before heading back east to see friends in Portsmouth, then home.

After booking into my small room in the Nags Head and then having spent a couple of hours near the sea front trying the fish and chips and a couple of pints of the local ale, I set off up what felt like a 45% hill back to the Nags Head. By the time I arrived, panting and crawling over the threshold, with one of the patrons saying to me “have you been out there the whole time?” to which I had no answer, I flopped at the bar, rationalising that I desperately needed a small whiskey before bed. With fortification in hand, I took a seat whilst the last of the punters supped up and left. On gazing around my eyes fell upon a picture on the wall. It spoke of more optimistic times and for a moment I felt privileged to be in this space.

Toasting the man

Lewesdon Hill, Dorsets highest point, was a thirty-minute drive northeast of Lyme Regis. I decided on parking up in the village of Broadwindsor, located just north of the hill. As I neared the village, driving along the B3162, a stationary police car was parked up on the road ahead. I drew up behind but was waved on. Just up the hill, a second police car was pulled over next to what appeared to be an abandoned car, and a couple of officers stood silently by, with arms crossed.

I drove on and within a minute was parked up in a small close to the south of the village. The weather was perfect. Almost too perfect. I had no summer clothing so chose to leave my coat in the boot. The OS Explorer map (116) showed a route out of the village and straight to the top of Lewesdon Hill. It required walking into the village, which was fine because I needed a snack and guessed that the settlement was just big enough to support a shop. Fortunately, there was a profusion of old-fashioned signposts, and on each the words, Village Shop, as if it was the biggest attraction in the area. Maybe it was.

Surprisingly, being a Monday, the small community shop was open, although in truth it was rather lacking in immediately edible stock. Reluctantly, (I had walked in and so walking straight out would have been seen as a tad rude) I settled for a rather unappetising looking vegan sausage roll thing, made by a large food company that rhymes with “balls.” The shopkeeper was almost certainly delighted to see the back of it, but hey, needs must.

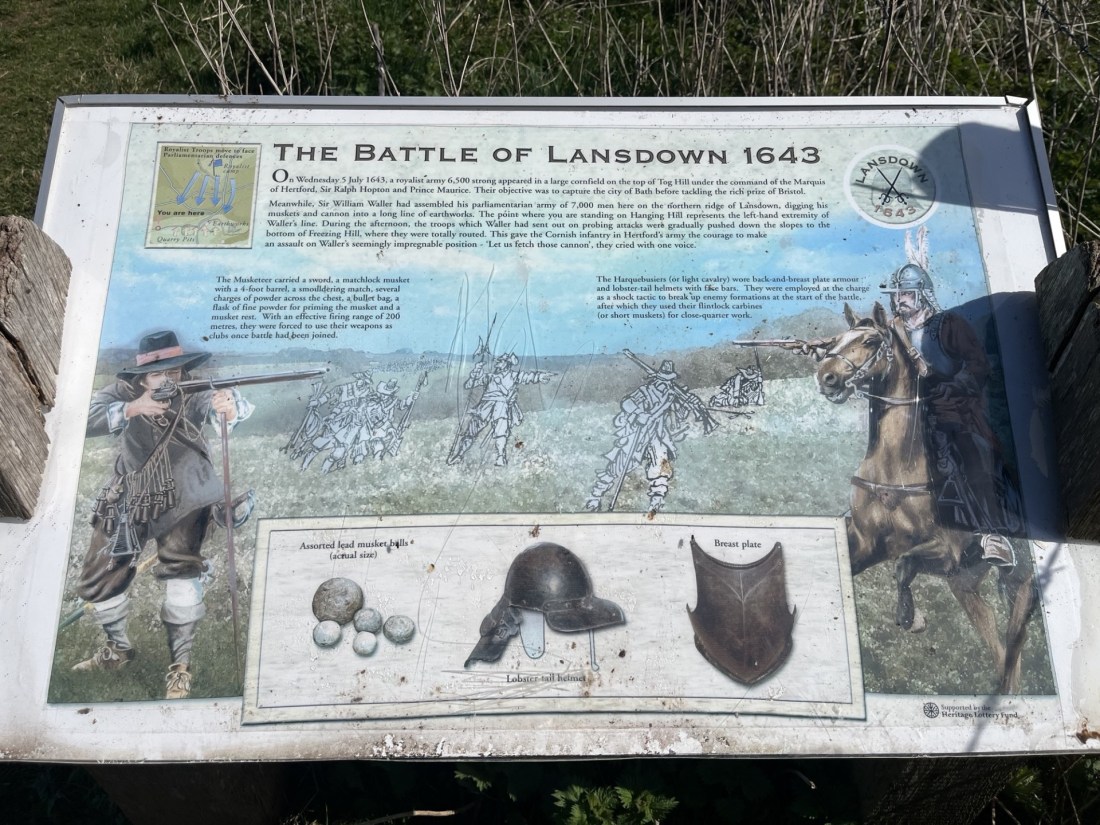

After procuring the snack and a cola, I walked back up to the White Lion Inn (closed Mondays) and headed west on err… West Street. A small house on the corner had a stone sign above the door that claimed Charles the Second had stayed there for a night in 1651. What it didn’t say is that he was fleeing from Parliamentarian troops after the battle of Worcester and escaped the village dressed as a woman. Just the previous day I had stood at the top of Hanging Hill in South Gloucestershire where, eight years before, a large force of his father’s military sustained appalling losses against a Parliamentarian army, taking the high ground before retreating.

Perhaps more interestingly, Broadwindsor also had a 17th Century vicar called Thomas Fuller who, apparently, often had his congregation in stitches. Who wouldn’t have wanted to live in a place which, whilst plague, and the warring elite ravaged the land, had a Sunday morning comedy club? I have an image of Paul Merton standing at the pulpit and drifting off into a flight of fancy, although having read a couple of Fuller’s “jokes” I think it’s likely that these days we would struggle to understand the nuance. By the time Charles the Second sought refuge in the village, Fuller was no longer the vicar, so missed the opportunity to crack a line at the King’s expense.

West Street wound down a hill to a bend in the road (which headed on up beyond). A footpath sign pointed south and confirmed the evidence on my map. Passing between a handful of buildings the path crossed a sparkling stream before reaching a large gate, with fields beyond. So far, so good. The gate, of course, was locked. There was no sign to indicate why. I don’t get annoyed in these situations, but it happens too often these days and can be mildly disconcerting. I looked around to see if I was missing something and noticed a small track leading away to my right, following the stream and through some woodland. It felt a bit unlikely, but I was in no rush so decided to follow the path and see where it took me.

Which was about 200 metres. The path petered out as it became overwhelmed by marshy ground. A delightful spot, but for me it was back to the drawing board, which meant a retreat to the gate. I looked beyond the gate and eyed up the path that clearly led to the top. No sign of a bull. I looked at the map, which showed an alternative path, but which required beating back through the village. I looked around. No one was in sight, so without further thought I was up and over and then stepping boldly along the path.

From there on it was reasonably straight forward, although at another locked gate a sign pointed east towards an alternative route, which I duly observed. After twenty minutes or so I arrived at a gate that marked the entrance to the Lewesdon Hill site, managed by the National Trust. Ahead lay dense woodland, with a variety of mature trees climbing up the steep slopes towards the top.

The approach to the enclosure

Proceeding through the gate, a large, mounted sign provided information about the area, the flora, the fauna and that an Iron Age settlement had probably existed on the site. That this seemed to be any doubt felt odd. It seemed to be a perfect setting. The board also stated that Lewesdon Hill was “the highest, quietest and most remote place in the county”. From what I had witnessed so far it felt a little bit like stating the bleedin’ obvious, but I wasn’t complaining.

A few steps on and a second sign. Slate grey, with the image of a Spitfire flying overhead in the top right-hand corner. I anticipated a sombre story.

In summary, on 15th March 1942, Jean Verdun Marie Aime De Cloedt, a Belgian in the RAF, in poor weather and with a faulty engine, crashed into the top of Lewesdon Hill. The commemorative board also mentioned that it was still possible to see the destructive path the plane had taken through the trees at the top. It felt like an unnecessary detail, but regardless it was a poignant tale. An intimate human story at “the highest, quietest and most remote place in the county”. Wars and hilltops. It was becoming a theme.

Chert stones that must have travelled down from above and onto the sandstone bedrock, scattered the path that headed south towards the top. Unusual, but would almost certainly have made this an attractive spot for early flint pioneers.

Within five minutes the path broke from the cover of the trees onto a heathy plateau and continued towards the only point that looked slightly higher than the surrounding topography. There was nothing of note to pinpoint the spot, but a hump of grassy earth seemed to be the place. I looked out to the south and towards the sea some miles away. Rays of sunlight swarmed through the large gaps between the trees. Looking down the steep escarpment the sun on the otherwise stark branches revealed the first, almost indiscernible, green blush of new growth.

From the top – Looking south southwest towards Morecombelake

Despite the delay in making progress at the foot of the climb, (due to the locked gate) I had made good time, and so after taking a few bites from the almost inedible vegan roll (cardboard wasn’t included in the list of ingredients, but I think it should have) I followed another path heading west and above the drop to the south. And a considerably steep and long drop it was too. Despite almost qualifying as a cliff, ancient birch and oak trees rose up from below, climbing and clinging on bravely to the thin earth. At some point it occurred to me that this was likely to have been the area where Jean Verdun Marie Aime De Cloedt’s plane had torn through the trees. I chose not to try and work out where.

Reaching the end of the plateau area another notice board gave more information, which must have made no impact on me at all, given that I can’t remember a word. A view opened out. The land fell away, but then rose again to the top of Pilsdon Pen, about two miles to the west, which even from a distance revealed features consistent with a hill fort.

West towards Pilsdon Pen

Scrambling down the north slope, on land recently cleared of larger trees, I was back on the main track which forms part of the Wessex Ridgeway and banked up to the right. The sound of a helicopter overhead intruded but tailed off as it headed north. Soon I was back at the entrance with the information boards, and after a quick look back set off across the first large field. I had noticed on the map that at the end of the field another path veered to the northeast and past Fir Farm. This was a more direct route back to the car and avoided having to negotiate the closed gate.

Objective Broadwindsor

By a large farm building I found what appeared to be the route, heading into some woodland. The noise of the helicopter should have long gone by now, but it was still audible, somewhere just to the north. Entering the woods, it was evident that the trail was little used. A sign had been attached to a tree, informing people like me that due to storms the previous year some of the trees were unsafe and walkers proceeded at their own risk. The sign itself was a year old, and I figured that the landowners would, by now, have taken the necessary action to make the area safe.

This was a lovely spot, a proper dingle dell. A low wall appeared ahead, with a nook cut out to allow the traveller to cross with ease. As I stepped over, something about its appearance had me confused. What kind of stone was this? I looked more closely. What I had thought was a stone wall was in fact a massive fallen tree, so embalmed in moss and lichen that it mimicked a human structure.

Not exactly sycamore gap, but art in nature nevertheless.

Carrying on down through the winding path the noise from the helicopter began to increase, annoyingly. Perhaps it was the military on manoeuvres, or a crop being sprayed with agent orange. Either way it was taking the edge off the afternoon. A bit further on and the path began to flank a track leading back to the farm. Looking ahead something stopped me in my own tracks. Through the trees and hedges, and about 200 metres further on, I could clearly make out the intermittent red and blue lights of a police vehicle.

In the 1935 film, The 39 Steps, Richard Hannah (Robert Donat), is on the run on a Scottish hillside when out of the blue (and out of all context given that Buchan’s novel was set before the Great War) a helicopter appears, hunting him down. Now, I should say at this point, nothing remotely interesting has happened to me for a very long time, although two evenings earlier in Bristol I had witnessed what might well have been a stolen motorbike being crashed at 5mph, and completely bizarrely, into a wall, before a car pulled up and swished the fallen rider away. Surreal. Nevertheless, and just for a moment, with the sound of the helicopter above, and knowing the cops were hovering somewhere just down the lane, my thoughts were suddenly hinting at the prospect of a manhunt! But who, and why? Was it fight or flight time?

Momentarily I engaged in mental research. Who was I? Robert Donat, Kenneth Moore, or, controversially, Robert Powell. I settled on Robert Powell, largely on the grounds that I had liked him a lot alongside Jasper Carrot in the TV show The Detectives. Now all I had to do was to get past the police checkpoint. Did I have my papers? It’s essential to have papers on you in these situations. I patted the inside pocket of my jacket. Hmm… would the Nectar loyalty card suffice? I was about to find out and started to walk purposefully towards the blues and twos.

I noticed that the police car lay beyond another vehicle and realised that I had reached the point I had passed in the car on my way into Broadwindsor. Whatever was going on seemed most particular. I reached the end of the drive and volunteered a “hello” to the two officers idly guarding the mysterious car. I think they may have said something back, but either way I wasn’t subjected to any stop and search, or interrogation, for which I was most grateful, although as I carried on along the road back into town, with the helicopter still bothering around above, I wondered whether the officers might have been a tad neglectful in their duties.

Back at the car I checked the app which had been recording the walk. 2.79 miles. 411 ft elevation gain. 670 calories. 8k steps. No more, no less. Oh, for 39 more! But never mind, for an hour or two, in a remote part of Dorset, which had once been the home of “Have I Got Sunday Morning News for You”, I had been away from the numbers.